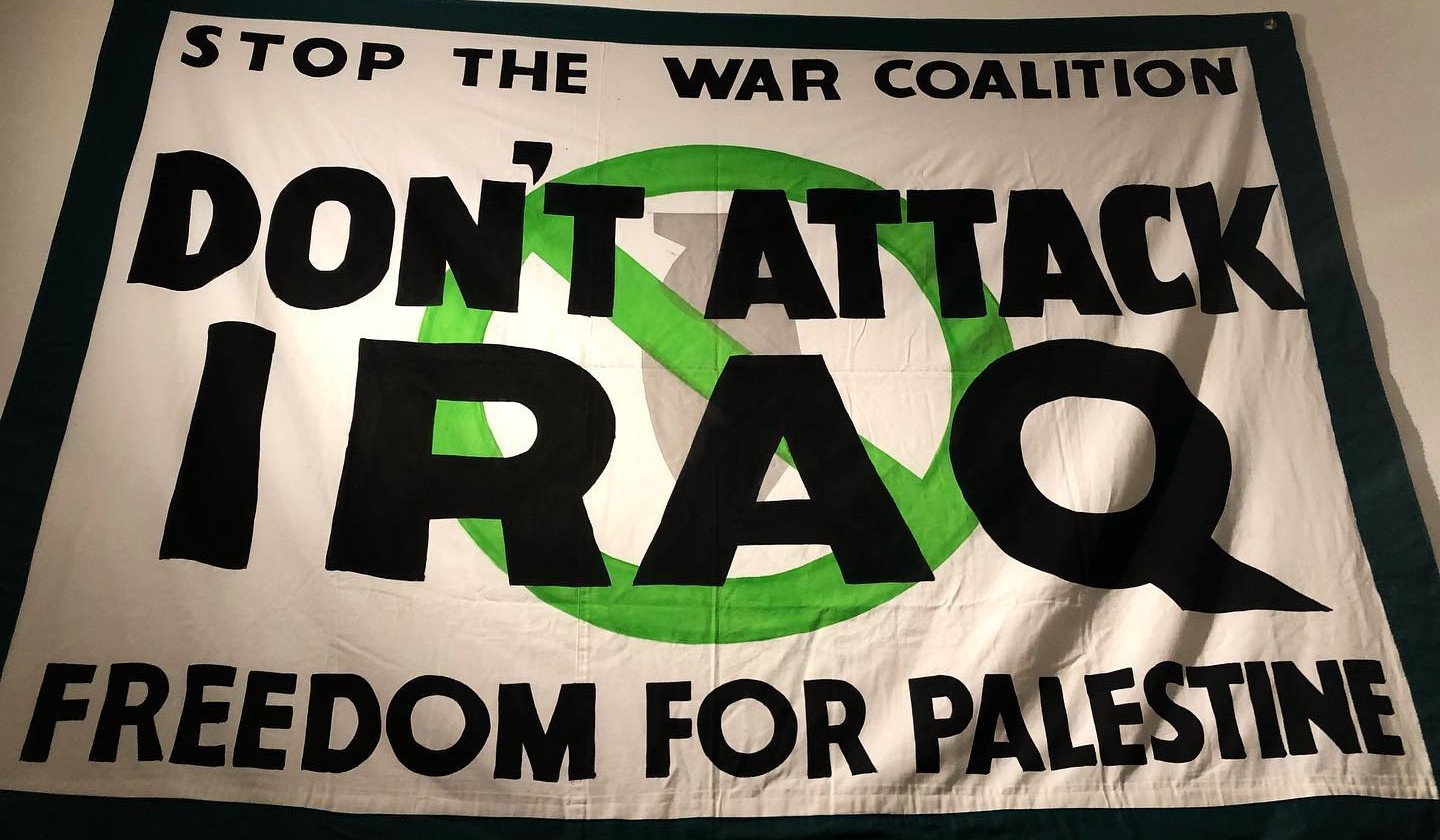

Stop the War banner. Photo: Counterfire

Stop the War banner. Photo: Counterfire

When the UK government declared it was joining the US-led invasion of Iraq, young people defied expectations and organised mass anti-war campaigns in schools and communities. Katherine Connelly reflects on the impact of their resistance

In 2003, when I was seventeen years old, I was arrested on a massive walk out from my Sixth Form college in Cambridge against the Iraq war. Twenty years on, it remains one of the proudest moments of my life.

No one expected our generation to take direct action for a political cause.

In the early 2000s, young people were routinely characterised as disaffected, responsible for little except anti-social behaviour and declining voter turnouts. In my politics class we were challenged to explain ‘why your generation is so apathetic’.

Apathy was a misdiagnosis of our contempt for a cynical, self-serving political class. Most grotesque of all was the New Labour government’s determination to join the neoconservative US president George W. Bush in a war on Iraq, despite widespread public outrage.

That’s when we, the supposedly apathetic youth, began to organise.

”There were two waves of school strikes. The first was on 5 March, the second was on the day we got the devastating news that war had started. That day we signalled to the whole movement that the only place to be was back on the streets.”

In our thousands, in our millions . . .

We were inspired by the largest global mass movement ever created.

In the UK, the Stop the War Coalition organised countless meetings, protests, stalls, stunts and, of course, the biggest protest in British history when around 2 million marched against war on 15 February 2003. Participating in this movement was empowering.

Ellie Harries who was a school student in London recalled: “The demos in London were exhilarating. I was at every demo, organising school strikes at my school, attending meetings at the weekend, leafletting, active in the Student Stop the War campaign…speaking to journalists, you name it I did it.”

When Ellie discovered Prime Minister Tony Blair was going to visit her school to launch an education policy, she helped organise a counter-demonstration with two hours’ notice: “It was an attempt to divert away from the war and I was so angry he was there, in my assembly hall, talking about education when he was plotting to go to war. I was raging. I shouted so much at the demo I lost my voice.”

Campaigning inside a mass movement gave students the confidence and experience to co-ordinate action across schools. We set up our own nationwide organisation, School Students Against the War (SSAW), where delegates from different schools began planning a huge walkout.

Alys Zaerin, at secondary school in north London, encountered her local Stop the War branch at their weekly stall which is where she first heard about the planned school strikes. She began organising straight away: “It was about five days after that I tried to organise one in my school. Other local schools had been organising for much longer. There wasn’t a particularly large turnout from my school. We joined up with the local schools and went to Parliament Square.’

Olivia Lavalette, a ten year old primary school student in Liverpool, was “inspired by all the college students walking out against the war. I wanted my voice to be heard too so I rallied my friends on the playground and refused to go into class after the dinner bell rang.”

There were two waves of school strikes. The first was on 5 March, the second was on the day we got the devastating news that war had started. That day we signalled to the whole movement that the only place to be was back on the streets.

A real politics lesson

In Katya Nasim’s 2008 documentary Day X: A Story of a School Strike Henna Malik from Kingston spoke about standing up in her politics class and telling her classmates “listen, if you want a real politics lesson, get your arses out onto that demonstration!”

One lesson we learnt was about the violence of the state.

In Cambridge, our peaceful sit-down protest was attacked by the police, anyone involved was a target to be violently dragged off the street no matter what age, and regardless of whether they were in school uniform. Piercings were viciously pulled out. The same thing happened outside Parliament where Alys was protesting: “Seeing kids being dragged across the road by police was a red flag moment for me. Things started to change for me then and other things seemed less important.”

We represented a different kind of politics. Whereas I was one of only two women in my politics class, SSAW seemed primarily to be led by young women. On the streets, Muslim students, some wearing hijab, and non-Muslims demonstrated together, blocked roads, linked arms, chanted through megaphones and made speeches. Perhaps, if they had chosen to, the government might have learnt a real politics lesson too – about what liberation actually looks like.

The government should also have realised that, after war on Iraq, politics could never be the same again. As Ellie Harries put it, “I never started out with faith in mainstream politicians, and I never will.”

Our demand for a superior standard of politics has never ceased to be expressed, try as the establishment might to suppress it. Alys reflected that “I didn’t join the Labour Party and probably never would do because of the Iraq War” but saw that for former students politicised about Iraq, Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of Labour seemed to be “another opportunity to shape things more progressively”.

Former SSAW member Elly Badcock traces her activism today to campaigning against New Labour’s warmongering and military recruitment in schools: “Nearly two decades later, this first experience of political betrayal still fuels my fight against capitalism, racism and imperialism.”

Olivia likewise remembers her: “first act of rebellion” as “the precursor for a lifetime involvement in activism!”

Ours was the last generation of school students to be called apathetic. Since then we have seen students walk out of school in internationally co-ordinated movements, most spectacularly over climate change. This new generation of school strikers understand the importance of not relying on small elites in parliaments or international governing bodies who are complicit in the devastation of the planet. They also connect the struggle against climate chaos to the struggles against racism, capitalism and war.

We did not stop the war in 2003, but our struggle was not defeated – it is unfinished.

Originally published in The New Arab

Before you go

Counterfire is growing faster than ever before

We need to raise £20,000 as we are having to expand operations. We are moving to a bigger, better central office, upping our print run and distribution, buying a new printer, new computers and employing more staff.