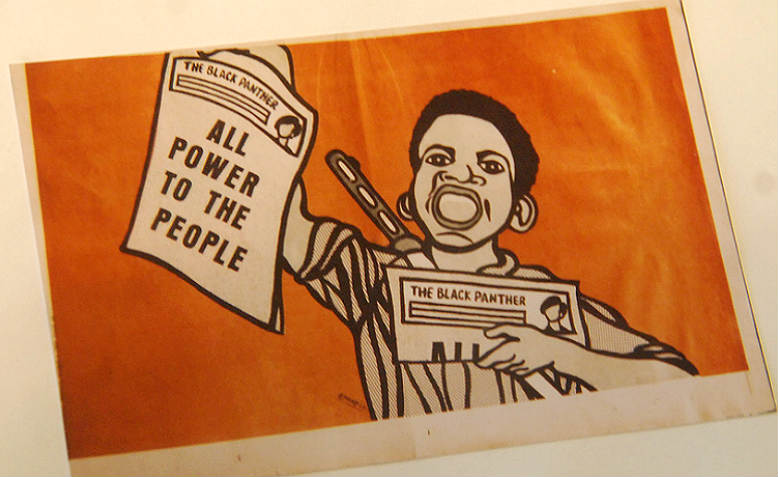

Publicity image from The Black Panther Party Newspaper, which was from 1968 to 1971 the most widely read Black newspaper in the United States, with a weekly circulation of more than 300,000. Photo: Flickr/Steve Rhodes.

Publicity image from The Black Panther Party Newspaper, which was from 1968 to 1971 the most widely read Black newspaper in the United States, with a weekly circulation of more than 300,000. Photo: Flickr/Steve Rhodes.

Our movements need media that inspire mass participation, amplifying analysis to reach new audiences turning to the left, writes Des Freedman

If music generates the soundtrack of our lives, then media provide the architecture of our political movements. They maintain our structures, amplify our analysis, inspire our base and connect us to others. Lenin once put it, talking about the Russian revolutionary press:

[it] could be compared to the scaffolding around a building under construction, marking its contours, facilitating the relationship between different sectors, helping them share the work and measure the overall results of the organized effort.

All our movements need a communications infrastructure with which to neutralise enemies, win new supporters and mobilise existing ones.

Every major campaign for social change has had its own media infrastructure: the Chartists had the Northern Star, the Suffragettes had their own self-titled newspaper and the Bolsheviks had Pravda; Gandhi founded Harijan to help build his anti-colonial struggle while Vanguardia championed the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War and the FLN had the unofficial Voice of Fighting Algeria during their struggle for independence from the French in the 1950s.

The left today has Jacobin, Democracy Now!, Novara, The Morning Star, The Canary, Evolve Media and now Counterfire Media, being launched as an expanded multimedia platform following the first eight years of its successful website.

None of the above are commercial enterprises but instruments with which activists communicate with each other, publicise their activities and spread their vision.

Such media platforms have been and can be organising frameworks for emergent mass movements designed not to simply rebut the news outlets of their opponents but to strengthen their own campaigns and, in so doing, to reach out to new audiences.

In the face of discredited mainstream media voices that are intimately tied to elite power and more keen to delegitimise Jeremy Corbyn than to go after the real power brokers in contemporary Britain, we have huge opportunities to win new audiences for our coverage.

We may not have easy access to major TV networks or be top of Google searches but more and more people are turning to left voices online to make sense of a world that has rendered our most celebrated commentators baffled.

Of course hashtags, video blogs and podcasts alone don’t topple governments, win elections and transform society but they can help solidify and give confidence to movements whose capacity to benefit from traditional communications system is limited.

So let’s not overstate the power of media in determining political opportunities for the left and let’s not fetishise media logic over its political counterpart. After all, it’s less the sophistication of a media strategy or a movement’s appeal to opinion formers than the strength of grassroots support and the ability to galvanise mass opposition that best determines the prospects for meaningful change.

But this shouldn’t stop us from providing the stories, analysis and interviews that are an essential component of building the movements that will challenge racism, austerity and injustice.

Nearly 50 years ago, the German radical theorist Hans Magnus Enzensberger wrote that:

For the first time in history, the media are making possible mass participation in a social and socialised productive process, the practical means of which are in the hands of the masses themselves. Such a use of them would bring the communications media, which up to now, have not deserved the name, into their own.

Enzensberger was celebrating the “emancipatory” potential of a media system in which “every receiver is a potential transmitter”. That applies not just to communications equipment but to people as well. Now we have the technical and political opportunity to really make this happen.