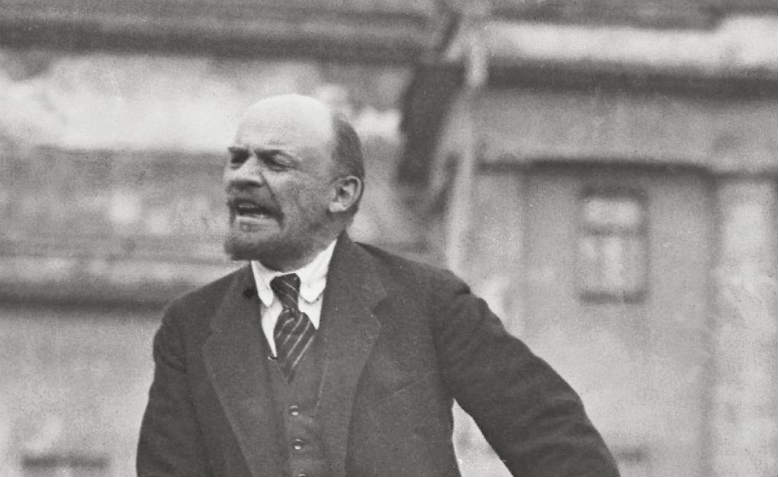

Vladimir Lenin speaking in Moscow,

Vladimir Lenin speaking in Moscow,

The centrality of anti-imperialism to socialism and class struggle has been disputed since before the First World War, but clarity on this issue remains vital, argues Elaine Graham-Leigh

We are often encouraged to see questions of foreign policy as existing in a separate sphere from domestic issues. This separation lends itself to the view that opposition to imperialism is an optional extra for those on the left. This was, for example, the essence of Owen Jones’ assessment of the Corbyn project, that Corbyn should have concentrated on the ‘red lines’ of public ownership, tax justice and investment and compromised on foreign policy.1

That this sort of ‘opposition at home, support abroad’ attitude towards government is so often seen as a sensible compromise, while insisting on the evils of imperialism is labelled as extreme, shows in fact the continuing importance of imperialism to the state. If imperialism were not central to modern capitalism, opposition to it would not be so derided by mainstream or centre-left opinion.

Lenin was clear that opposition to imperialist war was central to socialism, as imperialism is inherent to capitalism. The First World War (1914-1918) was, in Lenin’s words, ‘a war for the division of the world’2 between opposing imperialist powers. In consequence, understanding imperialism became an urgent priority for revolutionaries. Lenin’s aim in his 1916 pamphlet Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism was to provide that understanding and to explain why the response of socialist parties across Europe to the outbreak of the war had been so poor.

In the years before the war, the general position of the European socialist parties forming the Second International had been that any such clash between the major imperialist countries would be disastrous for the bourgeoisie and create opportunities for revolution. Nevertheless, they were clear that socialists should oppose it. As August Bebel said at the congress of the Second International in 1907, ‘we do not wish for such a dreadful means of reaching our goals.’3 From the beginning of war between Austria and Serbia, however, the Second International parties declared themselves unable to oppose the militarism of their own bourgeoisies. The position, as Rosa Luxemburg summed it up in 1915, was effectively that ‘Social Democracy is an instrument for peace but not a means of combatting war … the only policy befitting socialism during the war is ‘silence’; only when the bells of peace peal out can socialism again begin to function.’4

Lenin vs the Second International

Lenin, like Luxemburg, was appalled by this abdication by the socialist parties and by the consequent collapse of the Second International. As he wrote in his 1918 pamphlet against Karl Kautsky, one of the leaders of the German SPD, they had allowed themselves to be swayed by the bourgeois arguments into seeing the war as something other than simply imperialism. ‘An imperialist war does not cease to be an imperialist war when charlatans or phrasemongers or petty-bourgeois philistines put forward sentimental “slogans”’, Lenin pointed out.5

By accepting the lie by the bourgeoisie on both sides that the war was for ‘the defence of the fatherland’, the parties of the Second International had placed themselves in a position where they were demanding reforms from the imperialist bourgeois governments which they were in fact supporting. This, Lenin was clear, could never be socialism:

‘The imperialist war of 1914-1918 is a war between two coalitions of the imperialist bourgeoisie for the partition of the world, for the division of the booty, and for the plunder and strangulation of the small and weak nations … Whoever departs from this point of view ceases to be a socialist.’6

Lenin described it instead as a petty-bourgeois position, of loyalty to ‘their’ national bourgeoisies in war against other national bourgeoisies, even while they fought for concessions from them at home.

The parties of the Second International showed in 1914 that they saw the question of imperialism as something separate from the fundamentals of the class struggle in which they were still, formally at least, engaged. As Lenin quoted Kautsky as saying, imperialism in this view was a product of industrial capitalism, but ‘it must not be regarded as a “phase” or stage of economy, but as a policy.’7 Against this position, Lenin argued not just that the war was indeed imperialist, but that that imperialism was a stage of capitalism, not a political behaviour superimposed on it.

An understanding of the economic nature of imperialism, Lenin stated in the 1917 preface to the Russian edition of Imperialism, was thus essential ‘to understand and appraise modern war and modern politics.’8 He argued that capitalism had entered the imperial stage late in the nineteenth century, with five essential features: the concentration of production and capital into fewer, large corporations; the development of finance capital; the export of capital; the formation of international capitalist monopolies; and then ‘the territorial division of the whole world among the greatest capitalist powers.’9

Lenin was not the only Marxist to have noticed the development of monopoly capitalism, but there were different opinions about its effects. Kautsky argued, for example, that monopoly capitalism would see the end of wars, because multinational corporations would perceive such national struggles to be against their corporate interests. Versions of this argument have proved to be persistent, the modern incarnation being the idea that the spread of US corporations would prevent wars from breaking out. This has been shown not to work in practice. Thomas Friedman’s statement in The Lexus and the Olive Tree that no two countries which each had a McDonalds had ever had a war was contradicted by Nato’s bombing of Serbia in 1999, the year the book came out.10 In fact, Friedman’s point was not really that multinational corporations were forces for peace, but that there would be no need for military action if US corporations did not encounter resistance to their spread across the world.

Corporations and imperialism

The reality of the argument about McDonalds and peace highlights a key flaw in Kautsky’s view that monopoly capitalism would lead to an age of peaceful ‘ultra imperialism’: the role of imperialism in capitalist competition. Capitalism has an inherent need for constant growth, so corporations seek to find new markets and new sources of resources and labour. They do this not as equal players in a global free market, as mainstream economic theory would have us believe, but with all the advantages which state action can win for them against corporations from opposing nations.

Imperialism allows corporations from the imperialist countries to gain preferential access to markets in their empires, regardless of what the market would otherwise have delivered, as for example when the British empire destroyed the Indian textile industry to replace it with inferior British textiles. It gives them control over natural resources and ensures that infrastructure development in the colonised countries is carried out for their benefit, as in the creation of Indian railways by British firms. As Lenin summed it up, imperialism is a means for ‘the artificial preservation of capitalism by means of colonies, monopolies, privileges and national oppression of every kind.’11

Just as important as securing these advantages for corporations from the colonising country, the conquest of an empire denies access to the colonised countries to companies from opposing imperialist powers. Lenin observed how the acquisition of imperial possessions was as much to ‘weaken the adversary and undermine his hegemony.’12 Imperialist wars like the First World War are therefore not something into which governments sleepwalk, but an inevitable result of capitalist competition on a world scale.13

As Georg Lukács pointed out, Lenin’s analysis of imperialism is so valuable because it is not an abstract analysis, but represents a ‘concrete articulation of economic theory of imperialism with every political problem of the present epoch’.14 In this vein, it is important to understand that we continue to live in an imperialist world, even if those empires are now more about hegemony and influence rather than formal colonial rule.

Socialist politics and imperialism

Lenin recognised that governments wishing to secure popular support for imperialist adventures will always present them as justified responses to aggression, standing up to tyranny, and so on; the ‘defence of the fatherland’ argument which proved so effective in 1914 on the members of the Second International. His view on the position that revolutionaries should take was therefore uncompromising:

‘Socialists cannot achieve their great aim without fighting against all oppression of nations. Therefore, they must without fail demand that the Social-Democratic parties of oppressing countries … should recognise and champion the right of oppressed nations to self-determination, precisely in the political sense of the term, i.e. the right to political secession … A proletariat that tolerates the slightest violence by “its” nation against other nations cannot be a socialist proletariat.’15

This is not to say, of course, that opposing imperialist war is always easy, or that sections of the left will not be swayed by those bourgeois ‘sentimental slogans’, as we have seen for example with calls for arms to Ukraine and for Stop the War to wind up as a result of its condemnation of both Russian and Nato aggression.16 Lukács commented that the faint-hearted could see the revolutionary proletariat as isolated in its rejection of imperialism,17 presumably thinking of responses like the Austrian Marxist Adler’s to the declaration of war between Austria and Serbia in 1914, when he informed the Second International that:

‘The war is already upon us. Up to now we have fought against war as well as we could. The workers also did their utmost against war intrigues. But don’t expect any further action from us … I did not come here to address a public meeting, but to tell you the truth, that when hundreds of thousands are already marching to the borders and martial law holds sway at home, no action is possible here.’18

For Lenin, this was not simply a political failure but the result of a particular orientation within monopoly capitalism towards the interests of the bourgeoisie rather than the proletariat. As Lukács identified, monopoly development not only found support from the whole bourgeoisie and the petty bourgeoisie, ‘but even, (albeit temporarily) among sections of the proletariat.’19 In Imperialism, Lenin set out to show how the Second International parties’ collapse in the face of the outbreak of war ‘was not the result of a momentary aberration or of cowardice, but was a necessary consequence of their recent past.’20

That recent past included, from some leaders, distinct enthusiasm for their countries’ empires. At the congress of the Second International in 1907, for example, various speakers had argued that the imperial countries had a civilising mission to the rest of the world and that they were only extracting from the colonies ‘products that the native peoples had no idea how to use.’21 It is easy to see how a position of justifying imperialism before the world war paved the way for the International’s capitulation to their governments once war was declared. It is only possible to oppose war between imperialist powers on the basis of a principled opposition to imperialism if you do, in fact, have a principled opposition to imperialism.

Labour aristocracy

That various members of the International took a patronising and racist view of colonial peoples may come as no surprise to us now, but given the centrality of imperialism to capitalism and that they were supposed to be socialists, their support for imperialism when it came to the crunch nevertheless requires explanation. Why did the leaders of the parties of the Second International adopt the bourgeoisie’s interests over those of the proletariat? Lenin argued that it was because they had been effectively bought off by the bourgeoisie, in what would be the most controversial element of Imperialism, the labour-aristocracy theory.

That the leaders of reformist parties or trade unions can be led through the material advantages of their positions to identify more with the elites than with those they are supposed to represent is a recognised phenomenon. This seems to be what Lenin was thinking when he quoted a letter by Engels to Kautsky, in which Engels referred to ‘the worst type of English trade unions which allow themselves to be led by men sold to, or at least, paid by the bourgeoisie.’22 He also however quoted another letter from Engels to Kautsky, in which Engels expressed his exasperation with English workers who ‘merrily share the feast of England’s monopoly of the colonies and the world market.’23 This has been taken to mean something much more far-reaching: that entire sections of or even the whole working class of imperial countries form a ‘labour aristocracy’ who are bought off by their bourgeoisies and who therefore support imperialism.

It has been convincingly pointed out that while Lenin and Engels sometimes do appear to argue that sections of the English working class benefit from British imperialism, neither is clear about who that section might be.24 At most, Engels seems to mean ‘a small, privileged, “protected” minority’, as he put it in his 1892 introduction to The Condition of the Working Class in England.25 It is not tenable to argue that either Engels or Lenin really believed that the entire proletariat in any imperial country had been permanently suborned, hence the labour-aristocracy theory is often regarded as discredited.26

Aside from debates about what Engels or Lenin meant by the labour aristocracy, however, the idea that in order to oppose imperialism, the working class in the West must oppose their own material interests has not gone away. Japanese Marxist Kohei Saito, for example, argues that we have an ‘imperial mode of living’ which we must give up before we can overthrow capitalism,27 while Kai Heron, in defence of Saito, has recently posited that ‘solidarity [with the Global South] requires a degree of material “sacrifice” on the part of workers in the imperial core.’28

What is the labour aristocracy?

In modern discussions of the labour aristocracy, that aristocracy’s identity can be as unclear and shifting as it is in Lenin and Engels. In some versions, what makes you a member of the labour aristocracy is a matter of pay and conditions, so that ‘a permanent job makes you both an aristocrat and an exploiter.’29 This then becomes an argument that, because to be proletarian is to be relatively privileged, anyone who is in insecure employment is not proletarian at all, but a member of the precariat,30 and thus the proletariat is no longer the revolutionary class. In other, recent versions, membership of the labour aristocracy is as much about what you consume as where and how you work. Heron argues, for example, that ‘if you drink coffee in the US or Europe, eat chocolate, own a phone or wear clothes, you are in all likelihood a participant in the super-exploitation of the periphery’s lands and labour.’31

Heron’s comment is clearly intended to show how difficult it would be for anyone in the Global North to avoid membership of the labour aristocracy, and indeed, for some Third World nationalists, the argument became that all workers in the Global North join their bourgeoisies in oppressing the workers in the Global South. The idea of the proletariat being bought off by the imperialist bourgeoisie was extended by Franz Fanon and others to the proletariat in colonised countries as well. Fanon argued that ‘in the colonial territories the proletariat is the nucleus of the colonized population which has been most pampered by the colonial regime’ and therefore could not perform a revolutionary or a national liberatory role.32

At base, the argument across all these different versions of the labour aristocracy is that imperialism is supra-class: ‘it is not only the metropolitan bourgeoisie exploiting the colonial proletariat but the metropolitan society as a whole benefiting at the cost of the entire colonial people.’33 This is, in some versions of the theory, because super-profits accruing to companies as a result of imperialism are shared by those companies with their workers in the form of higher wages and better conditions. In other versions, it is simply that higher profits mean higher rates of investment across the economy in the imperialist countries, meaning that all workers benefit.34 The proletariat benefiting from these better wages and conditions is then too aware of its material advantage or simply too comfortable to be revolutionary:

‘That the lack of any revolutionary movement aiming at the abolition of capitalism in the rich countries may have something to do with the affluence of the workers there might, at first blush, seem equally uncontroversial. After all, as English Radical William Cobbett famously challenged in the early nineteenth century, “I defy you to agitate any fellow with a full stomach”’.35

The immiseration thesis

That the idea that only those who are in the most desperate conditions will be revolutionary can seem like a commonsense one may be because it represents a bourgeois understanding of the nature of revolutionary movements. Lenin, for example, quoted what he called the ‘crude and cynical’ comments of Cecil Rhodes on a demonstration of the unemployed in the East End of London, which for Rhodes underlined the necessity of imperialism:

‘I was in the East End of London (a working-class quarter) yesterday and attended a meeting of the unemployed. I listened to the wild speeches, which were just a cry for “bread! bread!” and on my way home I pondered over the scene and I became more than ever convinced of the importance of imperialism … My cherished idea is a solution for the social problem, i.e., in order to save the 40,000,000 inhabitants of the United Kingdom from a bloody civil war, we colonial statesmen must acquire new lands to settle the surplus population, to provide new markets for the goods produced in the factories and mines. The Empire, as I have always said, is a bread-and-butter question. If you want to avoid civil war, you must become imperialists.’36

Unsurprisingly, there is no understanding here of the nature of class consciousness nor of working-class organisation. Rhodes’ view was simple: give the people more to eat and they will go away and stop threatening you (and if they don’t, you can ship them off to the colonies). This was a nineteenth-century bourgeois view, but it can be found reflected in more recent arguments. Paul Mason, for example, argued in 2018 that the way to save ‘democracy, democratic institutions and values in the developed world’ was a programme to ‘deliver growth and prosperity in Wigan, Newport and Kirkcaldy – if necessary, at the price of not delivering them to Shenzhen, Bombay and Dubai.’37 This is not of course a Marxist understanding and is not borne out by the history of working-class struggle.

This is important because without the conviction that absolute immiseration is necessary to make the proletariat revolutionary, the idea that they can be meaningfully bought off falls apart. If the labour aristocracy is seen as synonymous with the entire proletariat, as many modern versions have it, then the theory becomes a form of trickle-down economics. There is no sensible mechanism for the entire workforce to be individually and carefully bribed; the bribe can only work if it takes the form of increased general prosperity across the economy. To argue that increased profits for corporations will automatically mean benefits for their workers is to argue that the interests of the capitalists and the workers, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, are aligned; that greater success for ‘our’ bourgeoisie will benefit us. This is the essence of the position taken by leaders of the Second International in 1914, but as Lenin argued, it is not one that any socialist should take.

Imperialism and class struggle

Those proposing the labour-aristocracy theory tend not to discuss the long history of struggle by which workers in countries like Britain have won better pay, employment rights, welfare benefits and so on. The implication appears to be that the bourgeoisie will grant these to workers once they have made enough profit to feel that they can, and that without the profits from imperialism, they would not have given in to workers’ demands, regardless of how hard the workers fought. Leaving aside the fact that there is no straightforward relationship between benefits and workers’ rights and imperialism (see the position of workers in the world’s major imperial power, the US), to uphold the labour-aristocracy theory, we would have to see a causal relationship between workers’ victories in struggle in imperial countries and the exploitation of workers in the Global South.

This is not a tenable argument. As Corr and Brown put it, ‘the suggestion that by abstaining from an organised and effective defence of their own position, the labour aristocrats would have benefited strata below them is unsubstantiated, moralistic and lacks a concrete understanding of class struggle.’38 It is by no means established that workers in colonised countries are invariably more exploited than workers in imperial countries. The difference in material living standards between the Global North and much of the Global South may make it appear evident that they always must be, but poverty is not the same as exploitation. Even if these workers were more exploited, however, the agents of their exploitation are the capitalists in the imperial countries, not the workers.39

Lenin’s understanding of imperialism did not rest on the sort of moralistic condemnation of workers in the imperial countries seen in many modern versions of the labour aristocracy theory. Rather than having to work against their own interests, imperialism provides workers with the opportunity to work in solidarity with the workers of the oppressed nations. ‘Imperialist war’ as Lukács argued, ‘creates allies for the proletariat everywhere provided it takes up a revolutionary struggle against the bourgeoisie.’40 At a time when the war in Ukraine and Israel’s genocide against the Palestinians in Gaza have returned questions of imperialism to centre stage, the necessity for principled opposition to imperialism becomes all the more clear.

- Ed McNally, ‘Jeremy Corbyn Was Successful When He Stuck to His Socialist Principles’, Jacobin, 10 July 2020, Jeremy Corbyn Was Successful When He Stuck to His Socialist Principles (jacobin.com).

- V I Lenin, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. A Popular Outline (International Publishers, New York 1939), p.9.

- Paul Le Blanc, Lenin and the Revolutionary Party (Haymarket Books, Chicago 2015), p.190.

- Rosa Luxemburg, ‘Rebuilding the International’, Die Internationale 1, (1915), Rosa Luxemburg: Rebuilding the International (1915) (marxists.org)

- V I Lenin, The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky (International Publishers, New York 1934), p.62.

- Lenin, Renegade Kautsky, p.65.

- Lenin, Imperialism, p.90.

- Lenin, Imperialism, p.8.

- Lenin, Imperialism, p.89.

- http://www.thomaslfriedman.com/bookshelf/the-lexus-and-the-olive-tree/excerpt-intro.

- V I Lenin, ‘Socialism and War (The Attitude of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party Towards the War)’, Lenin on War and Peace. Three Articles (Foreign Languages Press, Peking 1976), pp.1-57; p.8.

- Lenin, Imperialism, p.92.

- See for example Dominic Alexander on historiographical views of the origins of the First World War: The Shadow of Recent Wars: Historians and the Origins of World War I | Counterfire

- Georg Lukács, Lenin. A Study on the Unity of his Thought (Verso, London and New York 2009), p.40.

- V I Lenin, p.26.

- Stop the War has exposed how hollow it now is. It should disband (inews.co.uk), 14 September 2023.

- Lukács, Lenin, p.43.

- Paul Frölich, Rosa Luxemburg. Ideas in Action, 3rd ed. (Pluto Press, London 1972), p.200.

- Lukács, Lenin, p.43.

- Lukács, Lenin, p.52.

- Le Blanc, Lenin, p.190.

- Lenin, Imperialism, p.107.

- Lenin, Imperialism, p.107.

- Kevin Corr and Andy Brown, ‘The Labour Aristocracy and the Roots of Reformism’, International Socialism 59 (1993), pp.37-74.

- Frederick Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England (Panther, London 1969), p.33.

- As a recent example, see Matt Huber and Leigh Phillips, ‘Kohei Saito’s “Start from Scratch” Degrowth Communism’, Jacobin, 9 March 2024, Kohei Saito’s “Start From Scratch” Degrowth Communism (jacobin.com).

- Kohei Saito, Slow Down: How Degrowth Communism Can Save the Earth, trans. Brian Bergstrom (Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London 2024).

- Kai Heron, ‘Forget Ecomodernism’, Verso 2 April 2024, Forget Eco-Modernism | Verso Books.

- Corr and Brown, ‘Labour Aristocracy’, p.38.

- See for example Guy Standing, The Precariat. The New Dangerous Class (Bloomsbury Academic, London 2011).

- Kai Heron, ‘The Great Unfettering’, New Left Review: Sidecar, 7 September 2022, Kai Heron, The Great Unfettering — Sidecar (newleftreview.org).

- Franz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (Penguin Books, London 2001), p.86.

- Aditya Mukherjee, ‘Empire. How Colonial India Made Modern Britain’, Economic & Political Weekly vol. XLV, no.50 (11 December 2010), pp.73-82), p.76.

- Charles Post, ‘Exploring Working-Class Consciousness: A Critique of the Theory of the “Labour-Aristocracy”’, Historical Materialism 18 (2010), pp.3-38.

- Zak Cope, ‘Global Wage Scaling and Left Ideology: A Critique of Charles Post on the “Labour Aristocracy”’, Contradictions: Finance, Greed and Labor Unequally Paid. Research in Political Economy 28 (2013), pp.89-129, p.90.

- Lenin, Imperialism, p.79.

- Quoted in Louis Allday, ‘Social Imperialism in the Twenty-First Century’, MR Online, 6 August 2018, Social Imperialism in the 21st century | MR Online

- Corr and Brown, ‘Labour Aristocracy’, p.58.

- For a discussion of super-exploitation, see Guglielmo Carchedi and Michael Roberts, Capitalism in the 21st Century through the Prism of Value (Pluto Press, London 2023), pp.134-140.

- Lukács, Lenin, p.48.

Before you go

Counterfire is growing faster than ever before

We need to raise £20,000 as we are having to expand operations. We are moving to a bigger, better central office, upping our print run and distribution, buying a new printer, new computers and employing more staff.