AMLO, the new Mexican president, represents a break from neoliberalism, despite the political limitations of his programme, argues Orlando Hill

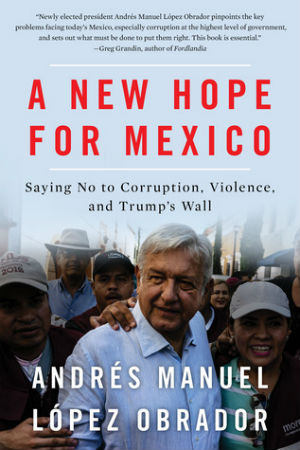

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, A New Hope for Mexico, ed. and trans. Natascha Uhlmann(OR Books 2018), viii, 209pp.

André Manuel López Obrador’s (AMLO) victory in Mexico’s presidential election on the 2nd July was greeted with a dose of scepticism by Counterfire. ‘AMLO’s accession to the Presidency is definitely an event to be welcomed by the left; not least, because senior members of the Trump administration have previously expressed their disapproval of the possibility, argued Sean Ledwith. However, ‘the likelihood is that AMLO as President will disappoint many of the millions who voted for him.’

Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first century we have seen various reformist governments, especially in Latin America, and we know how the story ends. The unshakeable faith that the state can be reformed from within eventually leads to a confrontation where the working class loses. Paraphrasing Lenin, it seems like one step forward, but two steps back.

However, in Mexico, AMLO’s victory was hailed by Ubaldo Oropeza in La Izquierda Socialista as ‘a great injection of morale, joy and confidence in their (the people’s) own strength, which is essential to understand how the masses will act in the next period, once AMLO takes control of the government’ in December. However, he warns his readers that what matters is not who is in government, but who controls the economic levers and the media. In Mexico as in other developing countries those are the local oligarchy sectors subordinated to imperialist interests.

Both Ledwith and Oropeza noticed that as AMLO’s campaign advanced it moved to the right in its desire to add more votes. AMLO made pacts with the reactionary parties such as Social Encounter Party (PES) and PRI members. His campaign was also supported by reactionary sectors in the trade-union movement. The weak internal democracy that existed inside Morena (AMLO’s party) was undermined as candidates were imposed from the top. This caused strong arguments, and some ended up in minor ruptures. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that AMLO’s victory offers an opportunity for the left to regroup and, while supporting the government’s reforms, pointing out the limits of the project.

A New Hope for Mexico offers an insight into AMLO’s views. It is a combination of two separate books previously published in Spanish in 2017: Oye Trump and La Salida. Oye Trump is a collection of AMLO’s speeches in defence of migrants, and La Salida is a broader political and economic platform focused on combating corruption. The speeches from Oye Trump are spread between the chapters of La Salida.

It is disappointing that the chapter in Oye Trump that deals with the genesis of the ‘pollero’ state was left out. Pollero (literally chicken herder) refers to the migrant smugglers who operate across the US border. The chapter was written by Pedro Miguel and he argues that the neoliberal policies implemented in stages since Miguel de la Madrid’s government (1982-1988) transformed the state of Mexico into a pollero. Mexico’s insertion into the globalisation process required that the country produce competitive exports. The problem is that the reduction of trade barriers and the lack of state support brought about a rapid destruction of the domestic manufacturing industry, which for decades had relied on protectionism. An inefficient and obsolete industry who owed its existence to a captive market was condemned to disappear when confronted with the world market.

Neither could Mexico count on the agricultural sector. According to the new economic paradigm’s logic, government agricultural subsidies were a heresy that had to be eradicated. Besides petroleum, which at the time was under state control, and illegal drugs, Mexico had little to offer the world market. Whether it was deliberate or spontaneous, the solution to this dilemma was for Mexico to export its labour force to an ever-avid US labour market.

The unemployed created by neoliberal policies had three options. They could head up north to the US. They could go into the illegal drug market. A third option was to work for one of the ‘maquiladoras’ (a manufacturer in Mexico owned entirely from abroad) where foreign corporations take advantage of extremely low wages, and where the working conditions are not very different from slavery.

This important chapter sets the tone for AMLO’s speeches, and it is a pity it wasn’t included. In 2017, AMLO delivered his speeches across the US understanding the urgency of reaching out to those who have been most affected by the economic recession. ‘We must help them understand that if they lack jobs, good salaries, and well-being, migrants are not to blame; rather, it is a result of poor governance that penalizes those below and benefits the wealthy’ (p.23).

Contrary to what Trump states, NAFTA has not benefitted Mexico. If it had, Mexico’s economy would not continue to stagnate, nor would migrants risk their lives crossing the US border. In 1970, Mexican exports represented 7.8% of GDP, and the growth was at 6.5%. Today, exports count for 35.3% of GDP, and the economy has only grown 2.5%. Mexico exports goods assembled with inputs imported from the US. In AMLO’s opinion it is possible to create a better society on both sides of the border.

Migration strengthens nations. It is the cornerstone of humanity. We know that our ancestors left Africa and populated the entire planet. Anyone who builds walls and segregates populations insults humanity and our shared history.

AMLO’s economic programme breaks away from the paradigm of neoliberalism and globalisation. In some ways it sounds very similar to what Corbyn and McDonell have been defending: invest in the countryside, restore the energy sector, support job creation and growth, and restore and strengthen the welfare state.

According to Oropeza, some groups in Mexico, who define themselves as socialist revolutionaries, accuse AMLO of trying to save capitalism. He compares these groups to spoiled little children who see great historic events happening before their eyes but are powerless to intervene or change them. They are spectators on the margins of the movement.

Lenin once said that people learn from experience. This new government with its reformist programme will be a learning process of the limits of reformism. Any attack from the right on AMLO’s government must be met with massive mobilisations from below.

AMLO’s progressive measures that strengthen worker’s position under capitalism must be supported by socialists in Mexico and abroad. Of course, there will be certain measures that will favour the more reactionary groups that support AMLO. One example is the insistence in maintaining a balanced budget. In the book he is not very clear what he means by a ‘balanced budget’. Does he include investment? Or is it just the running of government departments? There are therefore real dangers that AMLO’s government could be forced to the right, and to betray its promise. For socialists, the answer is not to dismiss the possibilities of the new government from the start, but to build movements to counter the right, defending what should be defending, and pulling the government to the left. Within this strategy, there should certainly be firm criticism of AMLO’s limitations, that criticism should always be in a comradely tone.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, A New Hope for Mexico is available exclusively from O/R Books.