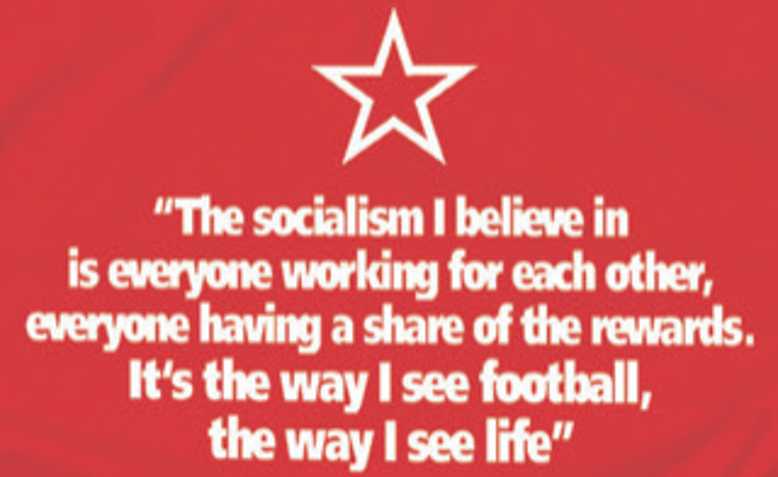

Shankly's socialism. Photo: Philosophy Football

Shankly's socialism. Photo: Philosophy Football

As the Labour conference in Liverpool continues, Philosophy Football’s Mark Perryman revisits Shankly’s Clause Four

‘The socialism I believe in is everyone working for each other, everyone having a share of the rewards. It’s the way I see football, the way I see life,’ Bill Shankly. In 1995, the newly elected Labour leader, Tony Blair, persuaded the party to drop ‘common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange’ from Clause Four of Labour’s aims and values. The left intellectual, and huge Liverpool fan, Doreen Massey found for us, Philosophy Football, Shankly’s ‘socialism’ quotation, and urged us to produce it as one of our T-shirts. In response, the fact that during his playing career Shankly wore Number 4 on his back at Preston North End, well, how could we resist.

An immediate hit, shortly after its release, the legendary DJ, and another huge Liverpool fan, John Peel, phoned me. Would I drop one round to his BBC studio, he was off to Glastonbury the next day to front the station’s TV coverage of the festival. This was product placement from heaven! The following week our post bag, pre-internet, was bulging to overflowing with orders. One was from the other reds, and deadly Liverpool rivals, Manchester United first teamer and legend Brian McLair; Shankly’s view of socialism’s appeal was universal.

Another left intellectual, Stuart Hall, had been there when Doreen hunted out the Shankly quotation from her bookshelves (this shirt had the most extraordinary of gestations). Almost a decade later in an essay, co-written with Alan O’Shea, Stuart set out a view of common sense that in many ways explains both the Shankly version of socialism’s appeal and its radical potential:

‘The battle over what constitutes common sense is a key area of political contestation. Far from being a naturally evolved set of ideas, it is a terrain that is always being fought over.’

Shankly’s description is of a socialism located in a core value for any successful team: individuals working together as a collective; that is to say, teamwork. And any rewards for the success that this delivers (it helps of course that Shankly led Liverpool to a lot of success) should be shared out equally too. Brilliantly, he then connects these values he instilled in the Liverpool boot room, training ground, and on the pitch at Anfield, to life beyond the touchline too.

What this amounts to is the mix of common sense with a distinct politics. Unless the two are combined, however accessible the language, it becomes devoid of any meaning in the doomed ambition of seeking to appeal to all. This week’s Labour conference has been meeting under the platform slogan: ‘Fairer, greener, future.’ What does that even mean? Is there anything in those three words to which anybody could possibly object? In what sense does this amount to political contestation of the sheer scale of the crisis into which the Tories, alongside the climate emergency, are plunging this country? And for those who suggest none of this can be achieved by a single slogan, in their very different ways Margaret Thatcher’s ‘There is no alternative’ and Tony Blair’s ‘Tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’ achieved precisely that: mapping out a distinct, easy to understand position from which to contest common sense, politically.

Hillsborough

As a footballing city, Liverpool provides a single tragic moment to reveal the horrific consequences when common sense isn’t contested. On the twentieth anniversary of the Hillsborough disaster, Andrew Hussey wrote a New Statesman essay, ‘A city in mourning, a game in ruins’, which made precisely this link:

‘A crowd being killed live on television in front of your eyes. A crowd little different from the working-class Liverpudlians of the 1960s who had inspired Bill Shankly’s greatest teams with their passion and collective sense of belief. The scenes of singing and scarf-waving on the Kop had been shown in black and white newsreels across the world.’

What did those pictures portray? Andrew’s description of their impact is suitably evocative:

‘This was the mob, the crowd, the working class in a group and in action, but it was nothing to be feared. The humour and dignity of this crowd were iconic. These images announced to the world the cultural vibrancy of ordinary people and their pleasures. To this extent, Liverpool fans were as crucial a component of 1960s pop culture as the Beatles.’

Yet, within two decades a successful and uncontested common-sense Thatcherism had entirely transformed this sympathetic representation:

‘By the end of the Thatcherite 1980s this same crowd had become the object of scorn and derision. To be working class, to be a football fan, to be unemployed and northern was to be scum.’

And on 15 April 1989, for 97 who went to a football match, it was to be dead. The decades-long fight for justice for those 97, which still hasn’t ended, has been as much about contesting this lethal ‘common-sense’ meaning of the crowd that day, as exposing the ways they were appallingly treated, and killed. The two are inextricably linked.

What was Shankly’s socialism in practice? From the campaign for Hillsborough justice to Steve McManaman and Robbie Fowler in ‘97 stripping off their Liverpool shirts to reveal underneath T-shirts supporting the Liverpool dockers’ strike (here’s hoping the current squad do the same for the 2022 strike). The matchday collections outside Anfield and Goodison, uniquely uniting Liverpool and Everton fans as ‘Fans Supporting Foodbanks’, which Ian Byrne, now a Labour MP, helped to found. Or the public campaigning work on issues including homophobia and Brexit of Everton legends, Neville Southall and Peter Reid. And Liverpool captain, Jordan Henderson, organising all his fellow, and rival, Premier League club captains to raise huge sums in support of NHS key workers throughout the pandemic.

The 2022 version of the Shankly Way, a common-sense socialism of contestation and solidarity: not a bad line-up to have at the back. But will Keir Starmer’s Labour even allow it on the conference pitch?

Further Reading: David Peace’s novelisation of Shankly’s life, career and politics, Red or Dead (Faber and Faber 2013).

Note: The Philosophy Football Shankly ‘socialism’ T-shirt is available from here.

Before you go

Counterfire is growing faster than ever before

We need to raise £20,000 as we are having to expand operations. We are moving to a bigger, better central office, upping our print run and distribution, buying a new printer, new computers and employing more staff.