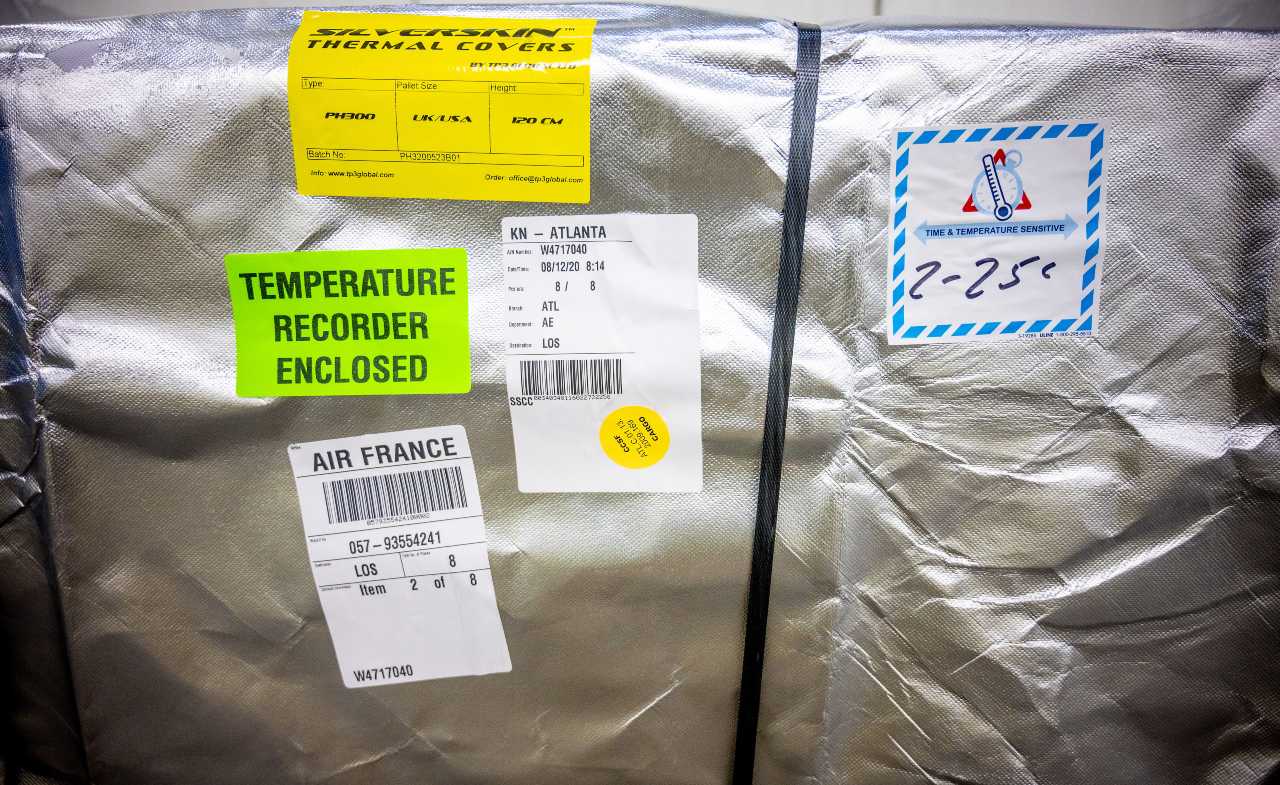

Delta delivers Covid-19 vaccine to France. Photo: Delta News Hub/cropped from original/licensed under CC2.0, linked at bottom of article

Delta delivers Covid-19 vaccine to France. Photo: Delta News Hub/cropped from original/licensed under CC2.0, linked at bottom of article

France’s beleaguered regime is undergoing a fresh battering, this time for the snail-paced roll-out of its Covid vaccination programme, writes Susan Ram

The figures said it all. On January 1, 2021 – five days after the arrival in France of the first batch of the Pfizer-BioNTech Covid vaccine – the number of people to have received it stood at the dismal total of 516 (just 0.001 per cent of France’s population).

Across the border, in Germany, the comparable figure was close to 200,000; in Italy, more than 79,000 people had been inoculated by the turn of the year. Even little Estonia managed to get the vaccine out faster, notching up some 2,500 vaccinations by January 1.

The publication of colourful graphs displaying the performance of rival players in the EU’s vaccine stakes – with France abjectly positioned in bottom place – could only add fuel to what quickly became a great surge of criticism. As a result, the start of Macron’s new year has been a fire-fighting effort – a panic-driven succession of statements, lurches and ministerial appearances geared to fending off fury by accelerating the roll-out of the vaccine.

What explains the exceptionally laggardly start to France’s Covid vaccination effort?

EU roll-out

Member states of the European Union received the go-ahead to begin mass vaccination following the approval of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) on December 21. Roll-out is being coordinated by the European Commission, and Brussels has struck Advance Purchase Agreements with multiple companies and secured enough doses to vaccinate the bloc’s 450 million-strong population.

The first delivery of the vaccine to member states was carried out on December 26, with states allocated doses based on their population size. France was allocated 1.16 million doses for this initial delivery, with a further 2.3 million to follow in January and February. The approval by the EMA of the Moderna vaccine on January 6 has boosted the projected inflow of doses.

The problem in France, then, has not been one of supply. But while there is general agreement that logistical and administrative lapses lie at the root of the roll-out’s pigeon-step start, there are conflicting narratives on the reasons for this.

Slow and steady wins the sceptics?

One narrative, advanced by the Macron government and taken up by political and media allies as well as sections of the international press, is that the French authorities are up against a uniquely recalcitrant, vaccine-sceptical general population, large sections of which are actively hostile to mass vaccination. From this it follows that that any roll-out can only proceed with extreme caution.

This provides context for the initial timetable drawn up by the government. In stage one (covering the two months until the end of February), vaccination was to be restricted to elderly people in residential care and health professionals judged to be at particular risk. Just one million people would receive the vaccine over this two-month period.

It was only in stage two (from March 1) that all those in the highly vulnerable age bracket of 75+ would begin getting their jabs. The plan was gradually to encompass those aged 65+ along with health workers aged 50+ or with underlying health issues. Something like 14 million people were to be inoculated during this phase, only after which would the mass vaccination programme be extended to the rest of the population.

In the event, it took only a few days for this snail-paced schedule to be effectively ditched. Public anger, the dismay of health professionals and epidemiologists, and opposition from a range of political forces, including within Macron’s ruling LREM (La République en Marche) party, combined to force the government into radically revising its vaccination timetable and ramping up the pace of the roll-out.

Under the new schedule announced by Jean Castex, Macron’s dour, charisma-free prime minister, at a televised press conference on January 7, the target of one million people vaccinated has now been advanced to the end of January. Very elderly (75 years+) people living in their own homes are now to be included in this initial phase. Mass vaccination centres are to be rolled out in each département (county) and procedures and protocols are to be simplified.

This turnabout suggests that something other than (or in addition to) generalised public hostility towards vaccines underlies the feeble start to France’s mass inoculation campaign. Despite Macron’s citizen-blaming explanation (his assertion that — annoyingly– the French combine extreme scepticism towards the vaccine with impatience for its arrival), evidence is building of major lapses at the highest levels of government.

Incompetence and bungling on high

Not surprisingly, it has fallen to investigative journalists operating outside the mainstream media to lift the lift on what has actually been going on. On January 6, Mediapart, an online news and analysis site created by reputed journalist Edwy Plenel, published a story titled ‘Campagne de vaccination: l’histoire d’un naufrage’ (Vaccination campaign: the history of a shipwreck).

Among its findings:

- The million or so Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine doses delivered to France in late December have been lying blocked in a handful of national centres

- One reason for this is that while France has 113 medical freezers capable of storing the vaccine at the prescribed temperature of -70 degrees Centigrade, only 28 of these were operational by the week beginning December 28 (the scheduled start of the vaccine roll-out)

- The failure to get the first batch of vaccines out quickly means that France has already lost three weeks of precious time when compared with Germany, the UK and other European states

- In logistical terms, France is ill-prepared for a vaccination campaign on this scale. Rather than draw on the expertise of supply chain specialists, the government has placed the whole weight of roll-outon the creaking shoulders of Santépublique France (SPF), its underfunded and overstretched national public health agency

- The unfolding logistical nightmare is evidenced by the delivery to hospital pharmacies of wrongly sized syringes and needles. Deliveries of doses intended for vulnerable health workers have also fallen woefully short of the mark.

Characterising France’s snail-paced vaccine roll-out as a scandal, rather than as something ‘forced’ on the government by a resistant population, positions it as the latest of a series of catastrophic lapses and failures.

For example, as the pandemic took hold in the early months of 2020, the Macron government failed its citizens by bungling the sourcing and provision of masks – all the while seeking to cover its tracks by putting about the fiction that mask wearing offered little protection.

Vaccine scepticism in France: some perspectives

There’s no doubt that scepticism towards vaccines is an entrenched attitude held by broad sections of people in France. A recent Odoxa-Backbone poll for FranceInfo and Le Figaro, published on January 3, found that 58 per cent of those polled would refuse a vaccination: a rise of 8 percentage points when compared with a month earlier.

The same poll revealed significant variations across age, sex and social background. Significantly, 58 per cent of respondents aged 65+ welcomed the prospect of vaccination (younger people were far less enthusiastic). In terms of political leanings, supporters of the far-right Front/Rassemblement National were particularly hostile (68 per cent against vaccination).

But aversion to vaccination also appears to reach deep into the French left and working class. The poll found 60 per cent of those supporting Jean-Luc Mélenchon and La France Insoumise opposed to vaccination; hostility levels were also high among ouvriers (blue-collar workers).

Multiple factors contribute to this generalised sense of wariness and distrust in relation to vaccines. Particularly in rural France, ancient, pre-modern ways of thought persist; folk remedies linger along with the writ of snake-oil vendors in various guises. Even in sophisticated urban milieus and among the highly educated, vaccine scepticism can surface abruptly, to the consternation of those whose views have been formed elsewhere.

To some extent this appears linked to problematic experiences in the past: for example, fears generated by a vaccine against hepatitis B in the 1990s; the tarnishing of a 2009 vaccination campaign against H1N1 influenza by scares surrounding a weight loss drug that proved deadly for certain consumers.

But hostility towards mass vaccination programmes cannot be detached from French citizens’ profound mistrust of government: an edifice of wariness, suspicion and contempt built up over many years of failures, betrayals and increasingly authoritarian rule.

The readiness of the Macron government to invoke this sentiment in an effort to explain away its own failures is cynicism of the highest order – and further proof (if any were needed) that governments are not for trusting.

Before you go

The ongoing genocide in Gaza, Starmer’s austerity and the danger of a resurgent far right demonstrate the urgent need for socialist organisation and ideas. Counterfire has been central to the Palestine revolt and we are committed to building mass, united movements of resistance. Become a member today and join the fightback.