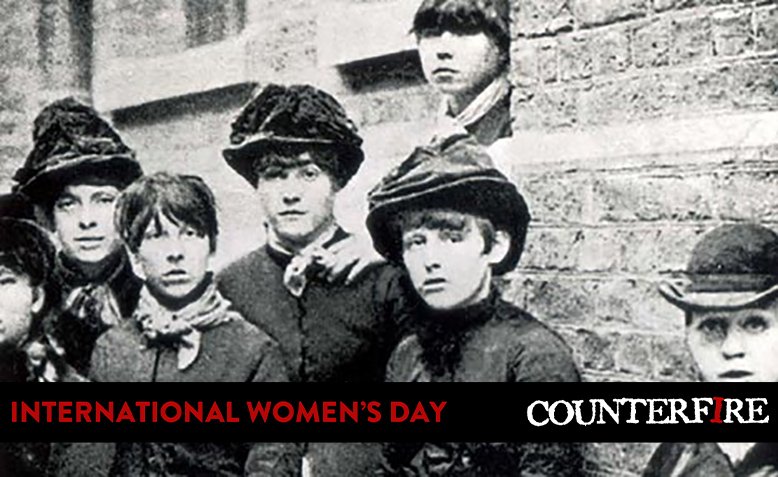

Bryant & May matchwomen on strike, 1888. Photo: Public Domain

Bryant & May matchwomen on strike, 1888. Photo: Public Domain

Ahead of International Women’s Day, historian Louise Raw spoke to Katherine Connelly about why it is so important that the 1888 matchwomen’s strike is remembered

Historian Louise Raw is the author of the groundbreaking Striking a Light: The Bryant and May Matchwomen and their Place in History (2011) which uncovered the stories of the matchwomen who went on strike in 1888 after attempts to victimise those who spoke out about the appalling conditions at the Bryant and May match factory in Bow East London. After years of work, Louise has successfully achieved official commemoration of the strike: on 5 July an English Heritage plaque will be unveiled on the site of the factory.

You have worked very hard to achieve a new plaque where the matchwomen’s strike took place. Your book Striking a Light proved that the strike was led by working-class women at the factory and not, as so many accounts had insisted, by Annie Besant a middle-class reformer and outsider telling the workers what to do. How does what you uncovered change our perception of what happened in East London in 1888?

It is so important, it’s everything really because without that version of events all you’ve got is a nice colourful story but it’s not empowering, it’s not particularly inspiring because it depicts the matchwomen as meek puppets, little waifs, little ‘matchgirls’ – a bit like the Hans Christian Andersen story.

This woman comes down to the match factory in her nice dress, presumably, and says “I say girls, we’re all going out, we’re going to have a jolly strike, because the Fabian Society have decided you’re going on strike”? It makes no sense.

Why would they do that without strike funds? These women are working hand to mouth. What working-class person would say “oh thank you Miss Besant, yes whatever you say”?

It’s ridiculous, it’s such a cliché, such a stereotypical view of working-class women as this undifferentiated mass. It draws on a lot of the images we get of East Londoners from the Victorian period: as the mob, the underclass, the wretched huddled together masses but they’re not people.

It’s an intensely Victorian model. We’re in a long Victorian period in some respects. It’s extraordinary what that teaches us. It shows us that that model of the great individual leading the masses dies really hard.

Obviously that’s going to be the establishment’s favoured narrative because it’s wonderfully disempowering. Because if you’re not a “hero” then you can’t do anything. You just have to wait and hope that your time will come, that your leader will come. It means being passive, having no belief in your ability to do anything.

And if you believe that you can believe that the matchwomen would just do what they were told by an authority figure. But if you’ve ever met humans, let alone working-class women, East End working-class women who I’ve worked with – it’s nonsensical.

It would be an extraordinary event if 1,400 people could be compelled for the political motivations of just one person to go out on strike. It takes all their agency away. It would mean I couldn’t say to girls in school: “these people were your age and look what they did.”

There are not that many plaques to working class people, let alone working-class women so it is really extraordinary that this is being put up. How do you think and how do you hope it is going to affect people who walk past and see it?

I hope that it will inspire people.

It’s important, we like to have fixed points and fixed monuments to go to and I’ve had a lot of people already saying “I’ll go down and see that”, “I’ll bring my daughters down and show them that when I’m in London.”

I hope the fact that it is a group of people being celebrated will inspire people too. That’s so different and unusual.

And I hope it will be a source of pride to the area as well: that we had these incredible women who were right here and who ruled the area.

I really hope it will, just in a small way, start a little bit of a shift in people’s thinking.

It’s not because they were the only women to go out on strike, they weren’t. But because they stand in for women who’ve been historically neglected, hidden and devalued.

Hopefully it will make people think about other such stories and think: I remember my grannie talking about some women where I am, like the herring workers, and make them start thinking about the fact that there’s not just these fixed points in women’s history as it’s sometimes told. You know nothing, nothing, Suffragettes! Nothing, nothing, World War One! Nothing, nothing, World War Two! In fact, it’s constant from the peasant’s revolt onwards (we know that now because a woman’s researched it) and every movement ever since.

What your work also shows as well is that the matchwomen ignited New Unionism, a huge movement that transformed organisation in the working class.

That’s the big thing! It would still be a great story on its own because they formed the largest union of women and girls in the country at that time.

That’s not nothing against this ruthless employer who are so like modern capitalists. They manipulated their political friends, held fancy dinners, put up a statue of Gladstone (for goodness sake, talk about sucking up!) and they were so good at having journalists round to show off their model factory.

It would have seemed impossible that anyone could beat their machine. They had a press machine, they’re friends with the government, they’re a huge player in the economy, they’re a massive exporter, they’re unstoppable . . . it seems.

That victory would be good on its own. But we also look for influence in labour history, did they influence and inspire their peers?

And that fascinated me in the research. Historians who had written the odd line on the matchwomen – there wasn’t much in any depth, or any new research – were saying “obviously they didn’t influence anything else. The next year, 1889, there was this huge New Unionism movement, but it’s a complete coincidence that it was in the same part of London.”

And I thought how could you say that so confidently unless you’ve researched that?

The minute you look at it, though, you find the leaders of dock strike shouting their heads off about the matchwomen all through the 1889 Great Dock Strike.

The Great Dock Strike and the Beckton gas workers are heralded as the stepping stones to modern trade unionism and the foundation of the Labour Party.

And the dock strike leaders were saying to the dockers: don’t give up, there are hundreds and thousands of you out there and you’re tired and hungry and the company say they won’t give in . . . but remember the matchgirls! They won their strike and formed a union. Remember the matchgirls, stand shoulder to shoulder like they did.

The matchwomen inspired them. They came down and talked to the dockers union three months after their victory – so that puts a rather different complexion on it. There are connections. The story’s been twisted to fit people’s unconscious bias.

You uncovered the names of matchwomen who led the strike. Could you tell us what impression you gained of what they were like and what gave them the confidence to stand up?

I suppose for me that was the most inspiring thing.

I had already got the impression that the story was wrong, that they weren’t these timid weak little women.

But I was fighting this very strong ideology that they couldn’t possibly have done it by themselves. I was told by a professor that they were only girls they were just (‘just’ and ‘only’ kept being used) Irish, teenaged girls.

There was also this view that what I was doing was feminist tokenism.

I was really stunned by it as a working-class person who has mostly worked with women and been on strike with women from East End families and worked in bars with really strong women.

I was surprised the extent to which people were not prepared to acknowledge this was even possible, that these women weren’t really like us, they didn’t think like us. But it’s not that long ago. I met people who’d known them.

So I had to really prove it was them and that was very hard because working-class women did not have time to sit and write journals or autobiographies, they wouldn’t have considered that anyone would have been interested anyway they were so looked down on. They didn’t have that ego or the time or the energy: working 12 hour days, coming home, scrubbing the house, feeding the kids, collapsing into bed, four hours sleep, up again. You’re not going to think “I shall now write my memoirs!”

I had a sense of them from when I discovered about the feather clubs, that they paid into communal hat clubs. That is resistance. It’s the sort of resistance I’ve encountered from working-class women because it’s a real pride thing that we’re not going to let people look down on us.

That gave me a real hint that they were not happy to just be in a little battered bonnet in the shadows. They were obviously buying really fancy clothes and sharing them, sharing their big, feathered hats. It’s a level of cooperation. A lot of things that don’t pass as formal industrial action are still resistance – I think that working class pride is a huge form of resistance.

I also found a magistrate complaining that when these matchgirls go out on their nights out they come back home singing the words of all the popular music hall songs and it is irritating to quiet-loving citizens.

Well, that’s interesting because again that’s not a description of passive little waifs. That’s a very cool girl gang. To apprise yourself of the latest lyrics of the latest songs you had to go the music hall, or buy the music sheets perhaps, and memorise the songs. They obviously took pride in it, probably like today if you can work out the latest rap lyrics. This is a very cool group with their own culture.

Then there was finding that there’d been a fake death threat – probably it was fake – sent to the factory soon after their victory from someone signing themselves “J. Ripper” saying he was going to kill some matchwomen because I hear they are beginning to say what they will do with me. So they’re not terrified; they were saying wait til we get our hands on him!

And then tracing relatives, which I was told not to do. I was told it would be impossible I was told they won’t remember, they won’t know, it’s not worth doing. I really, strongly remember that.

But as someone who hadn’t come from an academic background – I left school at fifteen – it just seemed to me the obvious way: talk to someone as close as you can get, who might have known them, who might have insights. It was a very non-academic approach. I put appeals in newspapers asking “was your grandmother a matchwoman?”

I found some amazing people like Ted Lewis and Joan Harris, whose grandmothers worked at the factory, and Jim Best, whose grandmother Eliza may have been the first one to walk out.

The stories I heard from them! I remember saying to them that there is this idea that Annie Besant told your relatives to go on strike. And they just laughed . . . telling my grandmother what to do?!

They were amazing women, they were tough because they had to be, because life was so tough, but they were so loving to their families. They were matriarchs, often for the whole street. The one who helps you in childbirth and lays out the dead and tells you which butcher will give you the bones at the end of the day if you’ve got no food.

They provided informal social services for the whole community. This is how the poor survive, these are their networks of solidarity and, again, this is resistance.

I remember Ted Lewis saying to me, I know people didn’t think they were ladies and that really was hurtful to us growing up, but they were to us, they were East End ladies and that’s the best kind.

They were these incredible strong women who buried children, had husbands disabled in the First World War, relatives with shellshock, brought up large families, were mothers, single mothers. These people are legends. If we’re going to build statues it should be to people like that.

They were intelligent, smart as hell, you have to be very clever, very resourceful to survive poverty, You can’t be dim, naïve and easily led.

Please can you tell us a bit about the unveiling of the plaque on 5 July and what it is going to mean to have the plaque on the site of the factory?

English Heritage are organising the unveiling. As I explained in a recent article, a lot of people have been involved in the process including Cathy Power and Rebecca Preston from English Heritage, and the wonderful residents at Bow Quarter, Liz Aitken, Sandra Docking and Simon Smith.

To me it’s wonderful. It would have annoyed Bryant and May so much that there on that Gothic front wall, right by the cottages where the foremen lived – the men who used to hit and bully the women – that this big, bold beautiful plaque is going to be right there.

The ghosts will be stirring.

I think about how uncowed the matchwomen were when Bryant and May’s idea of celebrating history and having a big event was to put that Gladstone statue up. The great and good were all there gathered and the matchwomen stormed the statue, pricked their fingers with hat pins and bled all over it and start yelling “our blood paid for this”. And they ruined the whole thing!

I like to think I’ll feel a little ghostly jostle from the matchwomen as I stand out there, by that wall, by that factory, on that street where they were picketing.

The plaque is being unveiled on 5 July at Bow Quarter, 60 Fairfield Road, Bow, London E3 2UB. Louise Raw is the organiser of Matchwomen’s Festival 2022 – more details here.

Before you go

Counterfire is growing faster than ever before

We need to raise £20,000 as we are having to expand operations. We are moving to a bigger, better central office, upping our print run and distribution, buying a new printer, new computers and employing more staff.