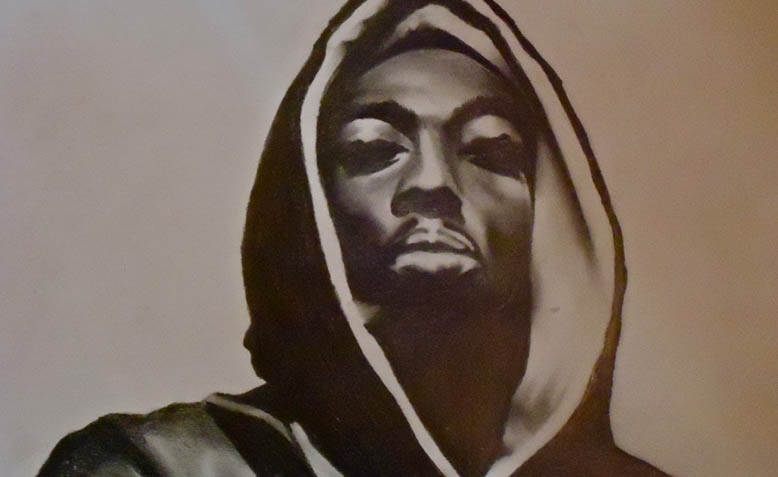

Drawing of Tupac Shakur. Photo: Wikipedia

Drawing of Tupac Shakur. Photo: Wikipedia

A look a the political life of Tupac Shakur, and the implications for today’s black movement, from Sean Ledwith

Coppers said Freeze, or you’ll be dead today

Trapped in a corner

Dark and I couldn’t see tha light

Thoughts in my mind was tha nine and a better life

What do I do ?

Twenty year ago, on September 7th, Tupac Shakur was gunned down by an unknown assailant in Las Vegas. He clung onto life for a few more days but the wounds he sustained proved to be fatal. Like many icons of modern American culture, his untimely death marked to be the beginning of a global phenomenon that would give him even greater fame than he had known in his lifetime. Of the 75 million Tupac albums sold worldwide, the vast majority have been since 1996. Part of the reason for his posthumous reputation has been the consistent release of material unpublished in his lifetime; 7 of his 11 platinum albums have been released since his death. The more significant factor, however, must be that his music of resistance still resonates with millions of people around the world, most obviously with African American urban youth. If anything, his powerful message of defiance in the face of an oppressive and racist state is become more relevant as the US stumbles from one high-profile incident of police violence to another, with no solution in sight.

The explosive rise of the Black Lives Matter campaign in this decade underlines the ongoing resonance of many of his lyrics and tragically provides a soundtrack to the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Michael Brown and scores of other black Americans killed every year at the hands of the US police. Like many revolutionaries, Tupac has been partially commodified and sanitised after his death; his image re-packaged as a dependable source of profit for record companies and fashion labels. He will never be entirely acceptable to mainstream US opinion, however, as his radical political heritage cannot be fully assimilated by a capitalist system that has racism at its core. When Ferguson was rocked by urban rebellion two years ago, many protestors carried placards bearing the words of Tupac.

Panther Legacy

Tupac’s radical political legacy was shaped even before his birth. His mother, Afeni, was a leading member of the Black Panther Party that challenged the US state in the late 1960s. Founded by Bobby Seale and Huey Newton in Oakland in the wake of the assassination of Malcolm X, the BPP represented an intensification of the struggle for civil rights that had gripped the country since Martin Luther King’s campaign against segregation in the South. Malcolm and the Panthers both marked a re-orientation of anti-racist activism away from the rural South and towards the urban northern cities; and also away from non-violence and towards greater willingness to confront the institutions of the state with the threat of retaliatory violence. The response of the US government was uncompromising in its ruthlessness and an object lesson in how capitalist states will resort to extreme brutality if threatened from below. FBI Director, J Edgar Hoover, created a new unit-the Counter Intelligence Program-specifically designed to destroy the organisation by any means necessary, and with a grimly prophetic goal to ‘Preventthe rise of a messiah who could unify and electrify the militant nationalist movement’.

Destruction of the Panthers

Over a 6 year period, 28 members of the Panthers were killed in gun battles with the police; most infamously, Fred Hampton, drugged and murdered in his sleep by Hoover’s agents in Chicago in 1969. In the same year, Afeni Shakur, along with twenty other members, was charged by the NYPD with plotting multiple bombings. Remarkably, she conducted her own courtroom defence, exposing the police case as a tissue of lies. She still had to spend the next two years in prison awaiting the verdict, and it was while behind bars she gave birth to Tupac in 1971. Even her choice of name for her son reflected Afeni’s radical background-Tupac Amaru being the name of an Inca leader in Peru who had fought Spanish colonists in the sixteenth century. Tupac acknowledged the sacrifices made by his mother, both during this period and later when she experienced crack addiction, in his track ‘Dear Mama’:

A poor single mother on welfare, tell me how ya did it

There’s no way I can pay you back

But the plan is to show you that I understand

You are appreciated

Tupac’s stepfather, Mutulu Shakur, was also an active member of the Black Panthers, spent many years on the FBI’s most wanted list and is currently serving a 60 year sentence in the US for masterminding a series of bank robberies. Tupac’s 1990 track ‘Changes’ references Huey Newton, the co-founder of the Panthers, who survived a police shooting in 1967, only to die 15 years later in an argument with a drug dealer:

It’s time to fight back that’s what Huey said

2 shots in the dark now Huey’s dead

I got love for my brother but we can never go nowhere

unless we share with each other

We gotta start makin’ changes

Contradictions

The crucial contradiction of Tupac’s tragically short life (dying at the age of 25) was that he was a child of the high tide of black nationalism in the late sixties and early seventies but had to grow up when the movement was in retreat due to the onslaught of the US state and political confusion among its most prominent leaders. Newton, Seale, Eldridge Cleaver and others argued over the strategic paths available to the Black Panthers; with the latter believing the party should go underground with an emphasis on guerrilla-style attacks on the police; while Newton and Seale argued for an increased participation in the mainstream political process. The combined effects of Hoover’s devastating Cointelpro network and this political fragmentation led the movement into the political wilderness as Tupac was growing up in New York and Baltimore. He witnessed not just the retreat of black nationalism but also the related rise of the New Right, most decisively in Reagan’s election to the White House in 1980. The spirit of collectivism and solidarity that had characterised the best of US politics in the 1960s was supplanted by the rapacious individualism of neoliberalism that stubbornly remains at the core of both the Democrat and Republican parties. Marxist critic, Tony McKenna, eloquently notes how this is the political context to much of the artist’s output:

Tupac’s tragedy, and his brilliance, lies in the fact that he was the living embodiment of this contradiction. He carried within himself the conflict between the universal tenor of community struggle and the narrow horizon of personal acquisition and individual gain.

Tupac himself was aware of how he represented a generation of black activists who had the misfortune to develop in the aftermath of a crushing political defeat and were struggling to identify a new trajectory in a society that appeared wholly unsympathetic to their plight:

It’s like, you hungry, you reached your level. We asked ten years ago. We was asking with the Panthers. We was asking with them, the Civil Rights Movement. We was asking. Those people that asked are dead and in jail. So now what do you think we’re gonna do? Ask?

Tupac and his generation had to locate a new personal and cultural strategy in the aftermath of the killings of leaders of the calibre and courage of Malcolm, MLK, Fred Hampton, and Huey Newton. They also had to seek it in a political environment in which Ronald Reagan, and then Bill Clinton, were regarded as the apex of political aspirations.

Thug Life

Many people might be deterred from Tupac’s music by the most reactionary aspects of the contradiction referred to McKenna; the undoubted misogyny and glorification of personal acquisition that frequently features not just in the rapper’s work but prominently in the wider hip-hop genre. The derogatory language and portrayal of women in some rap music and videos clearly represents a huge step backwards from the liberatory impulses of the 1960s; progressive trends that permitted women such as Tupac’s mother to attain an elevated status in the Black Panthers. Tupac himself was not always immune from this sexist mentality, and served a sentence for aggravated sexual assault shortly before his death (even though he always maintained his innocence). However, he was painfully aware of this dark side of hip-hop and understood the importance of curtailing it in order for the black community to re-connect to the long-term project of social revolution. His musical philosophy of ‘THUG LIFE’, as described in the iconic tattoo on his chest, was founded on highlighting not just the alienation and criminality that blighted the African American experience in the US, but also how those features were the product of the counter-revolutionary role models provided by the Reagan-inspired elite. The phrase was not, as his critics might assume, a mindless glorification of random violence but a crudely effective message on the roots of social inequality: ‘The hate you give little infants fucks everyone’.

From Tupac to Trump

Beginning under Reagan and continuing up to the present, levels of inequality in the US have intensified, providing the backdrop to the racism that would perceive THUG LIFE as nothing more than anti-social belligerence. Commenting on the hypocrisy of Reaganite trickle-down economics, Tupac observed:

How could Reagan live in a White House, which has a lot of rooms, and there be homelessness? And he’s talking about helping. I don’t believe that there is anyone that is going hungry in America simply by reason of denial or lack of ability to feed them. It is by people not knowing where or how to get this help.

Tupac’s uncompromising attacks on inequality brought the wrath of the establishment down on him in his lifetime. Vice-President Dan Quayle named Tupac specifically as a malign influence on American youth and was just one of countless conservatives to claim the hip-hop genre was the main source of violence in the black community. At the same time, mainstream politicians have occasionally tried to exploit Tupac’s ongoing popularity for political advantage. Republican Senator Marco Rubio, for example, recently making the laughable claim that he admired Tupac’s music but condemned his politics, as if the two could be separated.

Rubio’s campaign for the Presidency, of course, has been crushed by the Trump steamroller. The latter was already making a name for himself as the unacceptable face of capitalism in Tupac’s time, much to the rapper’s disgust: Everywhere, big business, you want to be successful? You want to be like Trump? Gimme, gimme gimme. Push push push push! Step step step! Crush crush crush! That’s how it all is, it’s like nobody ever stops.

It is intriguing to speculate on how Tupac, if he had survived the shooting in Las Vegas two decades ago ,would have reacted to the possibility that confronts America today of Trump being sworn in as the 45th President; possibly something the lines of his 1996 track ‘Trapped’-

It’s time I lett’em suffer tha payback

I’m tryin to avoid physical contact

I can’t hold back, it’s time to attack jack

Die by the sword?

Tupac’s murder is usually portrayed as a case of live by the sword, die by the sword. However, there is a political dimension to the shooting that has echoes in the shocking episodes involving more recent cases of denied justice such as Philando Castille earlier this year. Many would not want to go as far as author David Potash who argues Tupac was the victim of a similar act of state terrorism as the ones that killed Panthers in the 1960s such as Bobby Hutton and Fred Hampton, but comedian Chris Rock incisively highlighted how the rapper’s death is emblematic of the US elite’s disinterest in its most downtrodden communities, as manifested in the numberless unsolved African American deaths:

Tupac was gunned down on the Las Vegas Strip after a Mike Tyson fight. How many witnesses do you need to see some shit before you arrest somebody? More people saw Tupac get shot than the last episode of Seinfeld.