The removal of the vacillating President Castillo in Peru pits imperialist and oligarchic forces against the country’s social movements, argues John Clarke

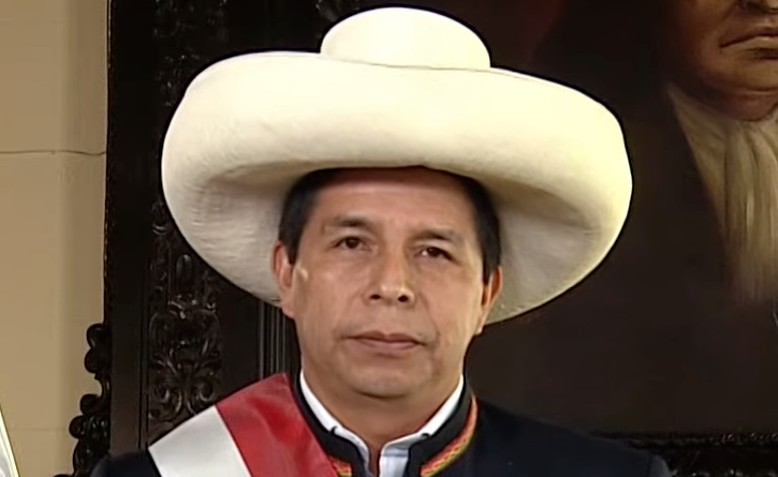

Explosive political developments are unfolding in Peru. On 7 December, facing a third attempt to impeach him, left-wing ‘President Pedro Castillo announced on national television that he had decided to “temporarily dissolve the Congress of the Republic and install an emergency government of exception.”’ Following this development, ‘Congress, the police, and the military rejected these acts and Castillo was arrested as he fled for the Mexican embassy. He has been placed in “preventive detention” for 18 months as he awaits trial.’

Having removed Castillo, the Congress, which has a right-wing majority, appointed Dina Boluarte, who had been his deputy, as caretaker president. In the wake of this, ‘social movements have mobilized across Peru, calling Castillo’s removal a coup and fighting for his release, the holding of new elections, and the drafting of a new constitution.’ The struggle has become very sharp, with brutal repression unleashed to contain the social uprising.

Right-wing attacks

In Peru, class divisions overlap considerably with the oppression of its indigenous population, and it is hardly surprising that indigenous organisations have played a leading role in the resistance that has broken out. There have been escalating strikes and roadblocks, and dozens of people have been killed by security forces. The Ayacucho People’s Defence Front has declared that these actions will continue ‘until Ms Boluarte resigns and new elections are held’, and a march on Lima to press the demands of the movement is possible.

On 20 December, with the uprising generating a major political crisis, the Congress debated proposals to call early elections. A majority voted to advance the next general election to April 2024, and also rejected the convening of the constituent assembly that Castillo had advocated as a means to advance constitutional reform. The conservative majority argued, ironically in the present context, that such a move might undermine the ‘tranquillity of the country’. It is highly unlikely that the opposition on the streets will be contained by these measures.

Those taking up resistance in Peru are challenging a right-wing attack that has the full support of the US and other imperialist powers. A State Department statement declared that: ‘We commend Peruvian institutions and civil authorities for assuring democratic stability and will continue to support Peru under the unity government President Boluarte pledged to form.’ At the same time, ‘Canada has recognized Dina Boluarte as the new president of Peru and has sent its ambassador in Lima to convey a message of support to the new government in person …’

At the same time, however: ‘At least 14 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have publicly expressed support for Peru’s President Castillo.’ These include Mexico, Colombia, Argentina and Venezuela. The realities of foreign domination and exploitation that dominate the life of Latin America are such that this sharp division over the new political regime in Peru could not be more telling.

There is no doubt that the political right in Peru and the capitalist interests it serves did all they could to undermine Castillo since he became president last year. ‘With a call to “throw out communism”, plans were made by the oligarchy’s leading business group, the National Society of Industries, to make the country ungovernable under Castillo.’

Alongside the efforts of business interests to thwart Castillo, the right wing in the Congress worked relentlessly against him. As Castillo himself observed earlier this year: ‘Since my inauguration as president, the political sector has not accepted the electoral victory that the Peruvian people gave us.’ The publication Alborado puts things clearly and accurately when it asserts that: ‘The oligarchic rulers of Peru could never accept that a rural schoolteacher and peasant leader could be brought into office by millions of poor, Black and Indigenous people who saw their hope for a better future in Castillo.’

Retreats

An understanding of the interests that are being served by the removal of Castillo from office, however, can’t go over to ignoring his considerable shortcomings and how these have contributed to the present situation. He took office in an electoral contest that saw him pitted against the right-wing Keiko Fujimori. He rallied to his side all those who opposed ‘Fujimorismo, the ideology associated with Keiko’s father, convicted human rights criminal and embezzler Alberto Fujimori.’

Castillo won the victory over his opponent by advancing a platform that ‘included creating a constituent assembly to rewrite the constitution, implementing a second agrarian reform, introducing university admission without entrance exams, renegotiating taxes on mining projects, and reforming the private pension system.’ The failure to move ahead with his promised agenda can’t simply be explained away as the result of right-wing obstructionism. His own vacillation and retreats have been a big part of the problem.

As he took office, Castillo claimed that he would ensure that there would be ‘no more poor people in a rich country’. This could only be realistically addressed if he was ready to confront Peru’s elites and the imperialist powers. Yet he immediately appointed, as his chief economic adviser, World Bank economist Pedro Francke.

The new president had previously talked of the need to nationalise ‘Peru’s mining and hydrocarbon riches’. Francke, however, was able to assert confidently that ‘we will not expropriate, we will not nationalise, we will not impose generalised price controls, we will not make any exchange control that prevents you from buying and selling dollars or taking dollars out of the country.’

In August 2021, Héctor Béjar was removed as Castillo’s foreign minister. He had made comments ‘criticizing the Peruvian Navy and the CIA for inflicting violence on the country’s population in the 1970s’, and the military threatened to put him on trial, insisting also that ‘he had to be booted from his post’. Following his ouster, Béjar stated that ‘I still think Señor Castillo is an excellent person [but] I do believe that this is a weak government.’

With enormous hopes placed in him, Castillo took power in a country that fully expressed ‘a systemic crisis of neoliberalism as a mode of governance and social order.’ He promised to address the racial injustices and the grinding poverty that Peru faces and to implement ‘substantial reforms in agriculture, education, health care, labor, and electoral politics’. The possibility of rallying popular support for these measures and moving forward with them has been squandered.

Made worse by substantial allegations of nepotism and personal corruption, Castillo’s track record of vacillation, appeasement and retreat only emboldened his opponents on the right, within Peru’s oligarchy and in Washington. His clumsy effort to deal with impending impeachment proceedings provided his enemies with a convenient pretext to move decisively against him.

The weakness that Castillo has shown in office must be compared to the courage and resolve of those who are taking to streets, going on strike and setting up roadblocks. They understand only too clearly the nature of the forces that are at work in this situation, and they are ready to face lethal repression, rather than retreat before the right-wing coup regime that is pitted against them.

Those who have now taken power in Peru are clearly facing an upsurge of social resistance that has them deeply worried. The movement that has been mobilised is putting forward vital demands that speak to the needs and aspirations of millions of working-class people. However, the task of building the political means to attain these is still very far from complete.

Before you go

Counterfire is growing faster than ever before

We need to raise £20,000 as we are having to expand operations. We are moving to a bigger, better central office, upping our print run and distribution, buying a new printer, new computers and employing more staff.