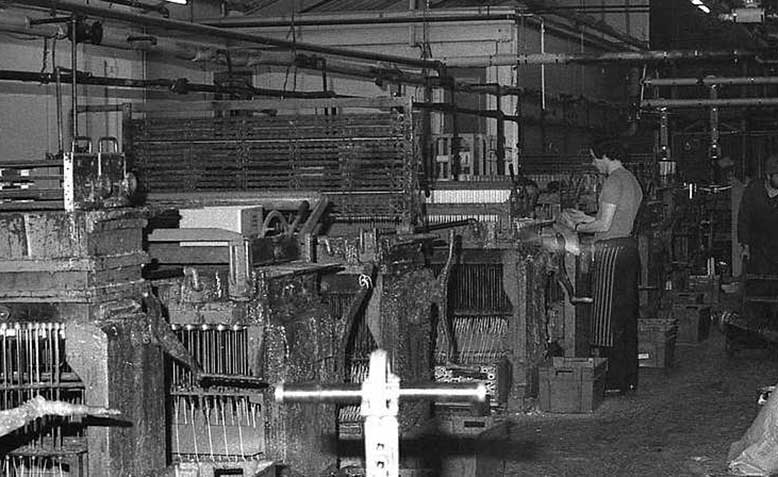

Factory with hand operated machines, 1970s. Source; Wikipedia

Factory with hand operated machines, 1970s. Source; Wikipedia

John Westmoreland conducted a series of interviews with workers on the front line struggling for health and safety in the 1970s

Stained with the blood of workers dead

Health and safety at work is uppermost in the minds of frontline workers across the globe in the midst of this pandemic. Trade unions are leading the demands for workers’ rights, and telling their members about the existing Health and Safety legislation, and how to use it.

The 1974 Health and Safety at Work Act and additional legislation that gives unions the right to elect their own health and safety reps is very important. Trade union recruitment and organisation are rightly centred on protecting workers at the moment.

Of course we should defend legislation that protects workers’ rights. However, the 1974 Act, passed by Harold Wilson’s Labour government, was long overdue – about two hundred years. Furthermore it has only proved effective when it is backed by strong trade union organisation.

Trade unionists active in the 1960s have bitter memories of dangerous workplaces where death and serious injury were commonplace. We talked to some of them. Kevin Pass was a miner in the 1970s who went on to become a full-time union organiser. Dave Freeman was an activist in the construction industry. Brian Kelly was convener at International Harvesters (later Case).

Some general points

The 1974 legislation is inadequate. As Kevin pointed out the language is often vague – “reasonable precautions” and what is “practicable.” This was deliberate because it allowed arbitration to involve legal experts and favoured employers. The Act puts the responsibility on the worker to keep themselves safe too. This means the trade unions can very easily slip into simply reacting when something goes wrong. It is much better (safer) for the unions to be proactive, as the NEU is today. For us, collective action and our industrial strength is the best way to keep workers safe.

Brian’s memory of the 1974 Act was that it was very limited, and allowed some employers to literally get away with murder.

For example, it didn’t cover oil rig workers because they worked in international waters, even though they were British citizens. A Doncaster MP, Harold Walker, was involved in drawing up the Act. He liked to say to Brian, “If every coal mine was completely safe, they would all have to shut.”

In 1988 the Piper Alpha rig explosion killed 167 workers in the North Sea. The cost of the damage was £1.7 billion too. The lesson is clear, unions need to be proactive, think ahead, and not rely on the bosses to keep us safe.

Asbestos: a killer cover-up

Asbestos was widely used in the industry after the war – in braking systems, paints, roofing, guttering, lagging, and insulation. The first death due to asbestosis was recorded in 1924. But because it was such a useful and versatile material it was increasingly incorporated into the industry.

The number of British workers killed by asbestos is unknown. ‘Scores’ of workers at the carriage works in York, where deadly blue asbestos was used, succumbed. The dangers were minimised by the bosses even when they knew it was lethal. Safely stripping it out of the existing plant, and finding safer materials was costly and made denial their best defence.

Dave Freeman remembers the campaign of lies and intimidation in the construction industry. “When you hear people like Richard Littlejohn sneering at ‘elf ‘n safety’ and calling people like myself ‘snowflakes’ I would just love to see him on a building site.”

Death and serious injury happened every day in the construction trade. Casual labour dominated construction and was known as ‘lump labour’.

Contractors were on a price and were prepared to risk lives to get it. Men died from being buried alive, falling from unsafe scaffolds, untrained machinery drivers, and asbestos.

Dave recalls:

“After I joined the building workers’ union (UCATT) we campaigned against being exposed to asbestos. Most trades came into contact with it and it helped us to recruit joiners, who tended to be more self-employed than the rest of us.

I am a painter and decorator. When I refused to scrape down asbestos gutters in Doncaster I got workers across the firm to back me up. It was a victory, but as a result, I got blacked in Doncaster and had to travel to earn a living. But we never gave up, and in the end, we won. Now it is official – asbestos is a killer.

And there is another thing. Men who worked with asbestos took it home on their overalls. This affected families through asbestos dust. Health and safety at work is about defending everybody. We have to look after each other because the bosses couldn’t give a shit as long as they are coining it.”

The movements are important

Another problem with fighting for health and safety workplace by workplace, encouraged by the 1974 Act, is that it is addressing the symptoms rather than the disease.

The best campaigners for worker’s health and safety have also campaigned for workers’ rights and against capitalism itself. The competitive and dynamic nature of capitalism to constantly increase GDP means that the system is progressive and revolutionary in developing science and technology, but left unchecked it is regressive politically and socially.

Capitalism started with slavery – a form of economic dehumanisation that is still around today. Slave rebellions were the main reason for ending the slave trade, but campaigners played an important part. The image below makes the point for us.

Nowadays the Tories are harking back to these good old days. They are neoliberals who adopt the most reactionary ideological baggage of emergent capitalism.

When Marx started writing about capitalism children in England slaved in mines and mills for up to 16 hours a day. Ending these practices took mass campaigns and collective organisation by Chartists and trade unionists. But has capitalism changed?

A 2011 UNICEF reports that “The number of child labourers in India is 10.1 million of which 5.6 million are boys and 4.5 million are girls. A total of 152 million children – 64 million girls and 88 million boys – are estimated to be in child labour globally, accounting for almost one in ten of all children worldwide.”

Kevin, Dave, and Brian argue that it is a mistake to try and deal with health and safety as isolated instances, with one workplace experience separated off from other identical experiences. We also need to draw on communities, campaigns, and the Left whose actions were vital in winning safer, cleaner workplaces.

Examples of campaigns that have changed things for the better are many. Women in communities dominated by a particular industry have often played the most crucial role.

Kevin mentioned the campaign for pithead baths led by Elizabeth Andrews in the Rhondda. Women and children had to bear a heavy burden in washing coal encrusted men and clothes – an unseen health and safety issue to the bosses. Elizabeth, an internationalist, a suffragist, and a socialist, organised a mass protest. She led women from the Rhondda to Westminster and they won.

Back in the 1960s the fishing industry was one of the most dangerous places to work. Health and safety on a trawler was whatever the skipper said. It was usually the advice to “keep one eye on your job and the other on the weather.” When three Hull trawlers went down the women of Hessle Road in Hull, under the leadership of the indomitable ‘Big Lil’ Lilian Bilocca, campaigned. Mass meetings, marches and petitions brought home the horrors to the public of trawlermen being ‘lost at sea’, and how their families were affected. Lil attempted to jump aboard a trawler setting off without proper radio equipment and had to be restrained by police. Health and safety aboard ship became national news and another seminal victory was won when the employers sent a mother ship with every fleet.

Militant workers live longer

Strong unions that use collective action when necessary gain the respect of the employers. Kevin recalls his time at Armthorpe pit in the 1970s:

“We had a lot of local rag-ups (disputes) over Health and Safety. If management asked a team to do something, and the job was potentially unsafe everyone on the face ragged up. You then fought for your pay in the office on the following Friday – or dispute day as we called it. I don’t recall any resistance from members of the team on any occasion.

It’s worth remembering the longstanding tradition at Armthorpe (and I understand most of the Doncaster pits) that if any miner lost their life through an accident the pit stopped for 24 hours. Management tried on each occasion to buy off the family and plead with the Union to continue working but they were never successful. The pit stood idle every time.”

Brian recalls an issue at International Harvesters when a chemical was used to degrease engine parts that was affecting workers.

“We made it our policy that all shop stewards were automatically H&S reps. The Left provided shop stewards with some great backup. They helped us find out about successful action elsewhere. An important Left publication was by a guy called Pat Kinnersley, who wrote about the Hazards of Work and How to Fight Them.

I marched into the manager’s office with a copy under my arm and proceeded to read out to him what was in the degreasant that was causing so much grief. It actually contained toxins used in Agent Orange – used by the Americans in Vietnam. He was shocked.

In the current climate we have to play the same role of educator and get on the front foot to keep our members safe. But we can only do that if we have collective strength.”

The lessons from struggles in the past are clear. We need to join trade unions and seek to be active within them. Winning small disputes through collective action has to happen before we can reach the big victories. Where we feel isolated and weak, we appeal to the broader movement for help. Above all, we have to remember that our lives are more important than their profits.

An injury to one of us is an injury to all. Solidarity.

Before you go

Counterfire is growing faster than ever before

We need to raise £20,000 as we are having to expand operations. We are moving to a bigger, better central office, upping our print run and distribution, buying a new printer, new computers and employing more staff.