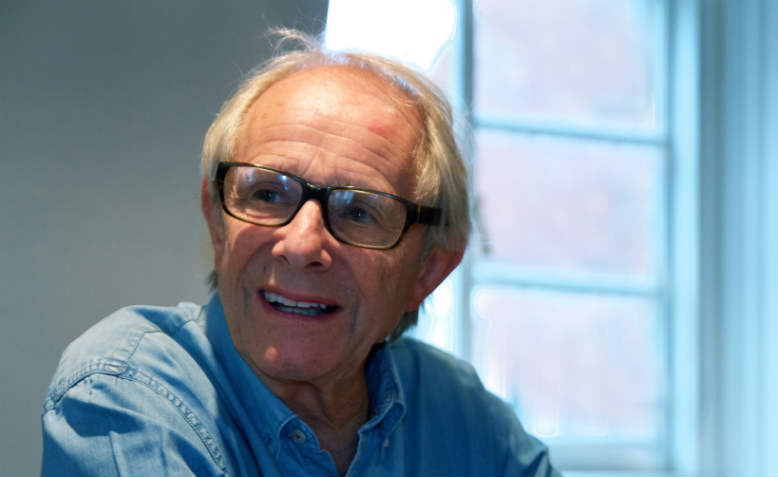

Ken Loach in conversation. Photo: Sheena Sumaria

Ken Loach in conversation. Photo: Sheena Sumaria

The award-winning film director talks about his latest film, his political influences, and the challenges now facing the left in a wide ranging interview with John Rees

I, Daniel Blake is already is already a critical success. Where did the idea come from?

A couple of years ago Paul Laverty, who wrote the script, and I were both hearing stories from people who had been sanctioned. One horror story was following another – stories about disabled people who had been reassessed and lost their benefits, problems with assessments where sick people were being forced to look for work, the rise of food banks. The stories just kept following one another. And we both also have connections to people who are running campaigns, Paul was hearing a lot of stories from them, so we thought maybe this is something we should make a film about.

So we did a little mini tour around five or six cities and towns. We began in my home town, Nuneaton, and on the very first day we went to a charity called Doorway, and there we were introduced to a young man aged 19, who wasn‘t getting benefits except for housing benefit. He did odd jobs, a few bob on the black economy, cash in hand. He was living in a room provided by the charity. The room was empty apart from a mattress on the floor and a fridge, and Paul said: Can we look in your fridge? So we opened it, and it was empty, there was nothing – no milk, no butter, no bread. We asked if he ever went hungry, and he said: Yes, the previous week he hadn‘t eaten for three days. And a friend of his, who worked through agencies, had been called at 5 in the morning to go across to the other side of town – Nuneaton is at the junction of various motorways – and went to a warehouse. At 6 o‘clock he got there and was told to wait. Half an hour later the floorman came over and said: What are you doing there? He said he‘s there for work. And the floorman said: No, not today, go back home. And so he went back home, obviously with no money.

So we thought we have to find a story that really says something about this.

Was it harder to generate that kind of story, where people are struggling under the system, than making a film about a revolutionary situation, where people are at the height of their power and confidence?

Yes, it was. We had to make a number of choices in the characters, and both Paul and I were really concerned that the disaster of having your money withdrawn, and being seriously impoverished and suffering the isolation and the depression that it causes, could happen to anyone. Cos obviously the stereotype is that you have an addiction, or you‘re feckless and so on. So we wanted to have as a main character somebody who was a skilled man, not an isolated person, somebody you wouldn‘t imagine this happening to. So in a way his descent, or what happens to him, should be all the more tragic.

But he‘s a cheerful bloke, and he manages, and the woman that he becomes friends with, is also very positive. We thought that the narrative needed a longer line than somebody who was already at the bottom to begin with.

It dramatises the commonality between people right at the bottom and people who haven‘t had quite to face that yet.

Yes, exactly. At the foodbank in Newcastle, where we filmed, last year had 2000 people in it. You‘re cutting into the heart of the working class here. It‘s not people around the edge who have had a major misfortune. This is whole swathes of people, and this is only one of a group of foodbanks in Newcastle. So I think it‘s cutting deep into working class experience.

Were you surprised by the critical response, for example in Cannes?

Well, yes. When you‘re in the middle of doing it you‘re still trying to evaluate what the response will be, because obviously you just film scene by scene and make them all work and hope that what you‘re thinking of will connect. But yes, there was quite an emotional feeling in the crew, but then you just don‘t know [what the response is going to be], and you get so used to seeing it when you‘re in the cutting room. So we were quite surprised. In our minds, it‘s a very logistically small film, we shot it in five weeks or so. In our minds it was quite a tight, short little story, so when it goes to the Cannes film festival, we thought: Wow, this is extraordinary.

Why are your films shown more widely in some European countries like France than they are in the UK?

The French have a different attitude to cinema. It has a different place in their culture, and it‘s seen as a cultural medium, alongside theatre, alongside music and concert halls. It seems to be a significant artistic medium, whereas here it‘s a commodity.

Some of your films, for example The Wind That Shakes the Barley, got a very different reception here than in continental Europe…

Yes, it was a very different here. The right wing hated it. I was compared to Leni Riefenstahl, the Nazi propagandist: A Tory MP and Times columnist said I was a worse propagandist than her. And Simon Heffer from the Daily Telegraphsaid: I haven‘t seen the film, and I don‘t want to see the film because I don‘t have to read Mein Kampfto know what a louse Hitler is. This is a respected columnist, he appears on the BBC frequently. He‘s not a far-right nutter – well, he is a far-right nutter – but he is sanctioned and welcomed by the establishment.

You‘ve just made your films available on YouTube. Why did you do that?

It was some time back, and I think some years ago there were any number of back films that people kept asking about, but nobody knew who had the rights, and Rebecca [O‘Brien, the producer] thought we can just put it on Youtube to be available to everybody. And there was no possibility to make any money out of them.

You have a background in the Trotskyist tradition, and there is a certain political take that‘s visible in your films. How strongly do you feel your political training and background has influenced the work that you‘ve done and the views you have?

That early involvement in the anti-Stalinist left was absolutely crucial for the way you see the world. I was back in the mid-1960s, and there were a group of us who went to meetings of the old Socialist Labour League, although I never became a member. And it was rigorous in its demand that if you wanted to take politics seriously, you have to read the basic texts to socialism. You‘d read a text and then you‘d discuss it on Friday, there would be questions and then you‘d understand it. I think organisationally there were serious problems with, as far as I could see, with most of those left groups, and the politics in practice was full of mistakes. But the intellectual rigour whereby you just had to examine history, and what were the forces within society that could effect change, and that was really essential. So it‘s had a big effect on the subjects we‘ve chosen.

When you look at the history of the labour movement over the last 150 years, what‘s not to agree with [the Trotskyist tradition]? Plainly, the social democrats have left us with mass unemployment, poverty, food banks, gross inequality and the destruction of the environment. So they failed. You clearly can‘t support the brutes who seized the Russian Revolution and murdered hundreds of thousands of people. But you can support the people who stood against both, who retained the basic analysis that capitalism produces classes which have conflicting interests, and if we are to live a decent life where everybody has a right to contribute to society, everybody can benefit from new technology, from the way we can feed everyone, house everyone, everyone can contribute. And that is the anti-stalinist left, which differentiates itself from the social democrats, who say that the only way we can get advances is if we gather the crumbs from the capitalist table.

Yes, that‘s what I was thinking when I grew up as a Trotskyist. What other tradition would you be part of? It was an anti-capitalist, anti-Stalinist tradition which rejects social democracy. Where else would you put yourself?

Exactly. But people don‘t understand it. It‘s a term of abuse without any understanding. And disgracefully, because there are some who ought to know better. Like people in the Labour Party, Tom Watson, for example. They are not stupid, and they are consciously using it as a term of abuse.

One of the things that left groups, among them Trotskyists, haven‘t been good at is a humanism, a kind of human sympathy, which was in the 1960 mostly associated with the work of E.P. Thompson. Was that something you drew on in the 1960s, or is it something that you just have to have?

I think it comes just from enjoying comics, really, the northern comics. Like many ordinary families, we used to go to Blackpool once a year. And you just see comic after comic, and I remember my father watching them with tears running down his face. And they were jokes about poverty and bodily functions, so it wasn‘t very sophisticated. It‘s just that raucus sense of the comedy of daily life. It goes back to Chaucer, it‘s in Shakespeare – it‘s a really strong strain in our literature and our culture.

…and it‘s naturally subversive.

Yes, it‘s anti-authoritarian. Comedy is a class issue. There aren‘t many posh comics, at least not intentionally.

It must have been great working with Ricky Tomlinson, who kind of embodies that.

Yes, we worked with comics first in Liverpool, in the 1960s. Up to then, a lot of actors in cinema seem to have come from down south and were putting on northern accents. Me and some others, we were young then, and with the temerity of youth we thought we can take it a step further, so we started looking for actors from the north. There weren‘t many of them, but there were many comics. So we went to the variety agency and met the comics that then did the northern club circuit, that was somewhere in the late 1960s. From then on we just cast comics an awful lot. They are funny and they bring a wit and an energy, and a self-confidence of who they are. There are many actors who arrive the first day and they are nervous and think who am I? These guys know who they are, they bring that buoyancy and irreverent take on the world, and it‘s there in the film. It gives them a strength and vitality.

When you cast non-professionals, not necessarily comics, do they bring a kind of personal confidence of who they are?

Yes. Casting is a long process: You start by having a chat, and then you do a bit of very simple improvisation, and then they come back and do another one, and so on. And by the time you‘ve done that 4 or 5 times, they‘re absolutely at home with it. And that‘s what they expect when they do the filming. To give it a sense of spontaneity, the actors can throw in their own lines. But when you cut the film, you cut back almost entirely to Paul‘s script. 95 percent of what is in the film is what Paul has written, but the actors feel like they own it.

How do you think socialist filmmakers can overcome challenges of funding and distribution?

I don‘t know the answer to that. If we hadn‘t been lucky at one or two points we wouldn‘t have been able to do what we‘ve done. Every few years, one or two new directors come in and I think it‘s luck in finding the right script and the right way of making the film, and then maybe getting it into a festival, maybe somebody seeing it and getting a good notice, maybe then somebody agreeing to putting it into a cinema. That‘s the traditional route, but it‘s a hell of a job to do it.

The other problem is that technology has changed, and it allows new ways of working. But for me, it‘s really necessary to work with a proper camera, a real cameraman who brings his own technique to it, a sound recordist and the designer will do the same. So you have all the different skills that are very refined and precise. Then you have an editor who shares the same sense of rhythm and has the same eye for what you‘re looking for, and I think everybody learns from each other. Moulding those into what should be a coherent, unified vision, that‘s what directing is about, but you need all those others present, and you can‘t do that without a proper budget. It‘s really difficult.

New technology now pushes filmmakers into thinking, well I‘ve been to film school, I can work a camera, I know how to put up a mic, and they make a film. And it may be that I‘m old-fashioned, but it may be that filmmakers can do something absolutely remarkable and unique and personal and valid, or it may be that it looks like amateur filmmaking.

Sometimes you see films where you think there‘s a good idea in there, but the script has been written by the one person who has directed it, and so it lacks that tension between the writer and the director. When we‘re shooting, it often happens that Paul would say: ‚Look, you‘re just missing something over there.‘ Or the cameraman would say: ‚I don‘t know if you noticed, but in the response his eyes wandered‘ or something like that. I was trying to do everything I wouldn‘t notice that. So you need the team. Writing and directing is the biggest heresy in filmmarking.

What is the significance of Corbyn, in how far can he further the interests of the working class, and what are the limitations?

It seems to me it‘s a moment in the Labour Party‘s history that has no real parallel. It‘s always been led by people who were social democrats. In the early days, Ramsay McDonald was a right-winger who walked away from the biggest conflict, the general strike. The high points after World War II, the welfare state and all its benefits, was established in order to provide a strong workforce that could fulfil the economic demands of that time, that capitalism needed to regenerate itself. It needed healthy workers, it needed them housed, it needed a secure infrastructure of energy, and water, it needed secure transport, and all that could only be done by public ownership, because private ownership had failed before the war. It‘s function was not to establish socialism, it was to establish an infrastructure with which business then could regain its position.

Jeremy Corbyn, it seems to me, is the first one who actually will stand for the interests of the working class when they are in conflict with the interests of capital. And if he were to chase out capital from transport, health. Investment in public industries and utilities etc. that would be a big setback for capital at a time when it needs to expand. It has this built in mechanism where it has to expand.