Photo: Women's Strike Assembly

Photo: Women's Strike Assembly

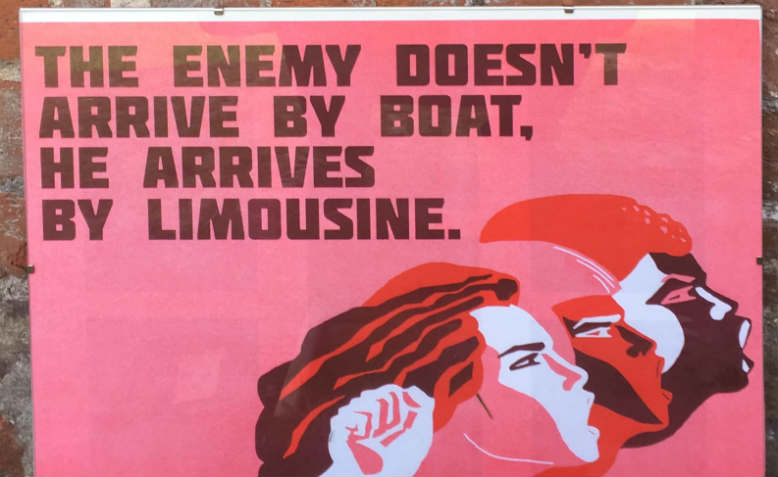

Capitalism creates displacement, and the left must be for equality of movement and the freedom of sending-countries, argues Hannah Cross

When Liz Truss and Suella Braverman reportedly rowed over immigration policy – between liberalising immigration rules for the sake of ‘growth, growth, growth’ and drastically reducing absolute numbers of immigrants – unsurprisingly, they represented two sides of the same capitalist coin. The promotion of migration flows that serve the market on one side, and of national chauvinism and anti-migrant hostility on the other, are critical and interdependent factors of capitalist wealth generation and ruling-class power. If we are to advance an anti-racist defence of migrants, we must recognise the common interests of the international labouring classes in a struggle against capitalist imperialism and global apartheid.

Free-market capitalism cannot run riot over land and resources without evicting people from their homes and livelihoods. This is why there was a ‘surplus’ UK population that Cecil Rhodes wanted to settle in colonised territories at the end of the nineteenth century, and why there are major displacements of people in the Global South today. The vast majority of migrants in the world do not become so by choice, but largely as a result of capitalist-induced displacement, by which they have lost the ‘right to stay home’, and are compelled to seek wage labour in distant places.

It is not that entire populations are evicted and on the move. The structural conditions of capitalism, as the dominant mode of production, interact at the household level with shocks such as family health issues, local environmental catastrophe, loss of livelihoods, redundancy or the intolerability of a life in which basic needs can barely be met. Such circumstances, combined with the economic means or social connections to migrate, drive people to take risks that might eventually allow households to be sustained at their normal level, with diverse and arbitrary outcomes.

In Africa, the 86% of migrants who are not fleeing conflict have been associated with uneven development and extreme poverty. Relatively few people leave their regions to enter the Global North by irregular routes, and the numbers are overplayed for scapegoating purposes. However, wage differentials, selective labour regimes that create brain drain and remittance dependence, the expansion of neocolonial borders and surveillance, and the denial of a safety valve, make the dynamics of South-North migration a major factor in global inequality.

Displacement as a feature not a bug

As Marx modelled in 1870, when he explained the need for English workers to stand for a free and independent Ireland, capitalism creates cheap labour when land and resources are expropriated and profits sent to the capitalist centres. People evicted by this process are then forced to move also to those centres – from Ireland to England in this case – and the capitalist class subsequently profits from lowered wages and working conditions. For Marx, the secret of ruling-class power was found in the way it intentionally aggravated the divisions between migrant workers and those who were native-born, via the media, entertainment and other state instruments. The only way to bring a ‘decisive blow’ to this power would be to unite and strengthen the working classes, domestically and on an international scale.

Comparable patterns can be found in Mexican migrations to the US following the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement, by which trade liberalisation led to Mexico being stripped of its resources. The dominance of US corporations over its land and resources destroyed livelihoods and poisoned the environment, leading Mexican migrants to make dangerous crossings, often working in the US food industry.

In West Africa, EU fishing agreements have depleted sea life and destroyed related livelihoods, leading to deadly boat migrations and desert crossings towards Europe. Echoing Marx’s letter, a Senegalese migrant living in Barcelona once told me: ‘All the time African resources come – diamonds, gold, bauxite, uranium; every day African things come here to Europe.’ He then quipped: ‘We want to be dispossessed of our things … and this does not affect anybody?’. In other words, to follow A. Sivanandan’s observation, ‘we are here because you were there.’

Illustrative of the deepening of globalisation since Marx’s time, it is not simply migrant workers being pitted against those who are native-born in the Global North: today, employers force different national groups into competition in agriculture, food processing and other industries through partial and temporary visa regimes. They also create competition with and between diverse native-born groups, whether agricultural workers in Canada, cleaners in the UK’s transport systems, meat industry workers in the US, and so on. This segmented labour force is enabled by the contradiction, a comfort zone for capital, of liberalised labour regimes and the state-driven prejudice enmeshed in border regimes.

A legal-bureaucratic structure that orders people on nationalist and racist lines with points-based systems, varied forms of citizenship, deportation regimes and militarised borders underpins a contemporary state of global apartheid. The overwhelmingly Eurocentric ‘mobility partnerships’ that the EU developed with sending-countries in Africa, which have included neocolonial border enforcement within the continent, labour mobility to meet Europe’s needs, and market-driven development projects in Africa, are emblematic of this age of imperialism.

What European countries have treated as a crisis for themselves also has a significant basis in imperial wars, including Nato’s destabilisation of Libya a decade ago, a country that had been an important destination as well as transit country for West African migrant workers. The increased circulation of weapons and militias due to this hasty military intervention led to the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people in Mali, as well as destabilising Niger and Burkina Faso. In the Sahel region, popular movements have been protesting against the French military presence and demanding a second independence.

The left cannot accept the treatment of forcibly displaced people as an infinite renewable resource to be controlled according to the whims of the market. As long as we are entangled with market liberalism as the rationale for mobility of people, militarised border systems, rooted in the imperial conflict of the First World War, will inevitably continue. Borders do not just keep people away, but also determine the circulation, citizenship and labour rights of people who cross them. The prevention of circulation between countries means people become trapped in host countries as well as being kept out, while also creating various forms of forced migration and exploitable labour. Borders have become a necessity to capitalist growth as well as a highly profitable, privatised industry that can only be dismantled with the destruction of their capitalist logic. Humanitarian pleas to open the borders to refugees will continue to be circumvented with false notions of illegality and illegitimacy as long as this logic continues.

Costs of global apartheid

While much of the focus so far has been on so-called economic migrants, the people who have been staying in Calais over months and years have been unambiguously displaced by conflict and persecution. Alongside the large numbers of Syrian and Afghan refugees, there are Africans from countries facing conflict and political emergency, including Eritrea, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, Chad, Gambia and Cameroon. Many are young men who were fleeing forced recruitment into armies and militias. Local authorities in France destroy their shelters, water supplies and dignity, adding to the fear and terror in people who have been traumatised by war and have been unable to live freely and safely in any country, often over many years. Along with connections people have with the UK and opportunities that might be found there, this state harassment explains why notifications of the UK Rwanda policy did not deter channel crossings, even though people in Calais repeatedly said that enforced deportations to Rwanda would lead them to end their lives.

The abhorrent treatment of migrants and refugees under the guise of fighting criminals – if not in the far-right’s outright criminalisation of migrants, then for the purpose of ‘protecting’ them against smugglers – is nothing new. Yet empirical research repeatedly finds that the smugglers and facilitators are often also surviving in a world system that destroys the means of subsistence and then closes safe migration routes. This is so whether it is Albanians helping their struggling communities to reach Italy, Nigeriens transporting migrants towards Libya, or ‘coyotes’ in Latin America, sending relatives and friends into wage labour in the US.

The world’s ’gulag archipelago’ has already seen EU policies to ‘return’ African migrants to countries they may or may not have passed through, and the detention of people who are suspected of wanting to leave Africa’s shores. This development has perhaps met its limits in the UK government’s failed attempts to deport asylum-seekers to Rwanda. It has been challenged by migrants and their advocates, trade unions, and even the airlines that find it too damaging to their reputation to traffic people – a process likely to result in deaths on board.

It emerged in a High Court hearing in July 2022, brought forward by asylum seekers, the Public and Commercial Services Union (PCS), Care4Calais and Detention Action, that there is a risk of forced recruitment to armed operations in Rwanda, which the then Home Secretary Priti Patel ignored. The PCS, which represents border-force workers, is also taking part in the legal challenge against the cruel detention facility in Manston, Kent that is treating people, including children, like industrial animals. It is unsurprising that Belize, Peru and Paraguay refuse deportation deals with the UK; they are part of a region whose ‘state of emergency’ in times of increased refugee flows is as likely to bring state assistance to people in need as it is to punish displaced people with military operations and prison facilities.

The need for an anti-imperialist approach

The Labour Party, going by the various proclamations of Keir Starmer and the shadow cabinet, sets itself against the Conservative government by offering to run an apartheid system of migration more efficiently and humanely. Their take downs of the Tory horror show may occasionally resonate, but the political outlook is a chauvinistic nationalism which does not speak for the working classes, wherever they were born.

The New Labour government, that Starmer’s leadership is trying to rehabilitate, set in motion new forms of criminalisation and undignified treatment of asylum-seekers through the construction of ‘illegal immigrants’ and other legal and bureaucratic measures of exclusion, supported by the press. It failed to support adequately the refugees it created in Iraq and elsewhere. It favoured labour-market deregulation for the sake of profits and growth, while treating the increasingly diverse working classes in deindustrialising communities with class prejudice and elitism. The left must reject this social imperialism, which also appears in many ‘post-capitalist’ perspectives. A social-democratic vision which omits due attention to the real acquisition of international land, resources and labour from its understanding of national wealth cannot contribute to a world free of structural, racialised and gendered social division and inequalities.

In this perspective, the argument for an end to militarism and for equality of movement between all regions and the West can be made without equivocation – not for the sake of propping up the West’s degraded labour markets, healthcare, food industries and other essential services that are the least valued by capitalism, but as a matter of dignity and justice which works in the interests of all working people. To stand for the independence and freedom of sending-countries does not mean supporting paternalistic aid programmes, extractivism and agribusiness, but instead means pressuring imperialist states to reverse their neocolonial practices wherever they are found.

The support of movements for popular sovereignty and autonomous development in oppressed countries, through trade-union movements, climate-justice movements, and other genuinely internationalist organisations, is also essential, as is the solidarity with informal workers and refugees that has been suggested by trade unions including the RMT and the PCS alongside Care4Calais and other rights-based organisations in the UK. Only then can the accelerating power and impunity of the ruling classes be truly challenged.

Before you go

Counterfire is growing faster than ever before

We need to raise £20,000 as we are having to expand operations. We are moving to a bigger, better central office, upping our print run and distribution, buying a new printer, new computers and employing more staff.