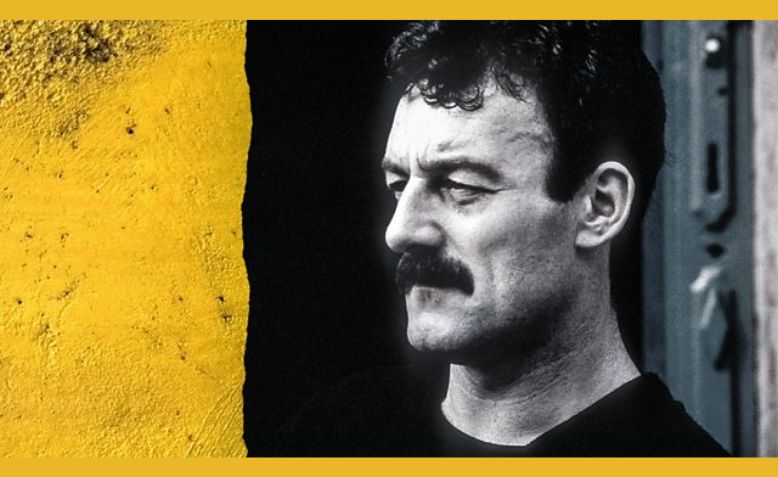

A still of Bernard Hill's character Yosser Hughes in Boys from the Blackstuff. Source: BBC Two programme guide/Image source linked below

A still of Bernard Hill's character Yosser Hughes in Boys from the Blackstuff. Source: BBC Two programme guide/Image source linked below

Forty years on, the landmark Liverpool drama remains as relevant as ever, argues Sean Coote

October 1982 saw the screening of ‘George’s Last Ride’, the final episode of Alan Bleasdale’s seminal drama, Boys from the Blackstuff. For the first time in several years, I watched its five episodes again recently. Time has not diminished it. Quite the opposite: it’s as relevant now as it was then. Maybe even more so.

“When you’re riding in your motor car and tearing through the shires, and the only sound you’re hearing is the humming of the tyres, you’ll be riding nice and easy then a smile will be enough, but don’t forget the boys that laid the old black stuff…”

So suggests the much re-imagined Irish folk anthem that kicks off Bleasdale’s 1980 Play for Today The Black Stuff, effectively the pilot for the series that would appear two years later. The song’s clarity and simplicity of message endures: give due regard to those who build, and those who produce.

Taking sides

Boys from the Blackstuff is a drama with the clearest of social contexts. In the 10 years since 1972, Liverpool, the great port of the British Empire, had lost 80,000 jobs and seen its manufacturing sector shrink by 50%. By March 1982 unemployment among the city’s economically active residents had reached more than 25%. As a drama depicting the human costs of what then Chancellor Geoffrey Howe called a managed decline (or a programme of economic and social vandalism), it has no serious equal.

When BBC2 screened the show in the Autumn of 1982 I was 17 and living in a Sussex village. Horsham was a constituency that would, 7 months later, return the Tory Sir Peter Hordern to Westminster with a vast majority. I had a materially middle-class upbringing but worked as a platemaker at the local weekly broadsheet. I was a member of the NGA and paid my political subs to Foot’s Labour. The union was the first institution that ever truly looked out for me, even when I was at fault. Not something I’ve ever forgotten.

Dennis Potter once described television as a place where the nation talks to itself. It ought not to be a passive presence, but one to encourage engagement, to question, and to voice concerns that may otherwise go unspoken. This was something that Alan Bleasdale clearly understood. Dramas such as Boys from the Blackstuff don’t appear as often as they should, certainly not without a subscription. When they do, the effect is life-affirming.

With no social media, it began as a word-of-mouth show, an episodic window on a Britain myself and my peers knew existed but was one from which geography and circumstance had distanced us. We were encouraged to live in a ‘southern bubble’, in which the media narrative cast scousers at best as thieves and scroungers, at worst as commie agitators. ‘Reds under the bed’, rather than a once proud industrial working class whose culture was being deliberately destroyed. Yet despite the socio/economic gulf that existed, class consciousness ensured that Boys from the Blackstuff nurtured a recognition and empathy in those from the south who worked in trades, or who were themselves on benefits. Crucially, it was that rarest of things: a television programme with real people in it.

The illusion of choice

Its tragedies and highlights are incessant. In ‘Jobs for the Boys’, Snowy Malone (Chris Darwin), a man with enough pride in his work to leave a small signature on walls that he’s plastered, dies whilst trying to escape a dole-snooper raid. The tone is set. In ‘Moonlighter’, ‘Dixie’ Dean (Tom Georgeson) gets a security job on the docks but is coerced into allowing a robbery on his watch. He has to balance the possibility of prison, and ruin, against the threats to himself and his family, and the cold economic reality. ‘Freedom of choice’ was a Thatcherite mantra, as if the choice is an end in itself. What would you do, the audience is asked. And we’re thankful we can defer the answer, or simply switch channels. That we don’t, speaks volumes.

‘Shop Thy Neighbour’ dissects a marriage destroyed by unemployment. Chrissy Todd (Michael Angelis), former alter-boy and spreader of the blackstuff, has lost his faith in God as surely as his wife has lost her faith in him. “For once in your life, fight back…” The dole snoopers that pursue him are as much the victims of the piece, rats in a cage, consumed by self-hate for the nature of their actions. We cheer for Chrissy when he finds a fiver down the sofa. We implore him to replace the bread he ate that was earmarked for his kids. We wince but understand when he spends it all on Scotch and chips instead.

Gis a job…I can do that

All serious artists, regardless of the fields in which they operate, want to be remembered for an undisputed masterpieces. With ‘Yosser’s Story’, Bleasdale surely succeeded. The seeds of Yosser Hughes’ (Bernard Hill) descent were sewn as far back as the pilot, when he had the last of his savings scammed. Here, the state completes the job.

Few hours of drama can claim so many lines that still, forty years later, remain seared in the popular memory. ‘Gis a job. I can do that. I can paint lines..’. That it manages, amongst the horror and the misery, to also be killingly funny, is some achievement. To Graham Souness, with a flourish of comic insanity, Yosser declares: You look like me. And Magnum… And in confession: I’m desperate… Call me Dan, implores the priest… I’m desperate, Dan…

Yosser Hughes, in the end, loses everything. His work, his family, and his home. But unlike Chrissy, who quietly subsides, Yosser goes down swinging, as do his kids. It may be the police that deserve the kicking here, but when his daughter head-butts the social worker observing their eviction, she does so on behalf of all those who failed (and condescended to) by a state that looked the other way. And here was the thing that people I knew most related to: Yosser was a man with the will to fight to the end, regardless of the odds, and the hopelessness of his position. For such a character to achieve folk-hero status in an English village in the Tory heartlands, was, looking back, quite something.

Rooted in the class

In ‘George’s Last Ride’, the priest presiding over George Malone’s (Peter Kerrigan) funeral tries to insist on his given Christian name of Patrick but is told he’s not on by Chrissy. Bleasdale is making the point that George spent his time on the streets, on the picket lines, and in the labour movement. The priest then gets drunk, talks George up despite now knowing him well, and vomits in the backyard. Being unmoored from his class was anathema to the old class fighter, right up to his final days. Such separation is a luxury the left can ill afford.

Watching it again, four decades later, one thing is clear: its representations of class, race, and gender seem less engineered, less formally arranged as object lessons than a lot of recent drama. Nobody in Boys from the Blackstuff needs to be announced as working class. They simply are, made real by a man who was one of their number. Chrissy’s wife Angie (Julie Walters) is a strong woman, raging at a system that’s destroyed her husband’s very masculinity. She’s no mere cipher, no box to be ticked. Throughout its run, attention is never drawn to the processes of its production. We, the viewers, are never lectured. We are not condescended to by cultural engineers, rather we’re invited to observe.

Then and now

Current political parallels to the landscape of the series are obvious. Conspicuous inequality, an economic elite willing to impoverish millions rather than see their privileges even modestly reduced, energy disconnections, a working-class monitored, lip-read and demonised when they stand up and dare to organise themselves. And the perennial classic: the scapegoating of benefit recipients in a nation where a corporate tax evasion is an art form. And all reported on by a docile and compliant mass media.

We’ve been left with a culture where human worth is brand-linked, policed by social media that relentlessly hound the non-conformist, were to disagree is increasingly inadmissible. Television drama, at its best, puts all this nonsense on pause. It grants us time to reflect on something like the real world, a world where meaningful choices are ever more restricted, or worse, an unaffordable luxury.

Norman Tebbit described the show as defeatist. Ironic, given it was the defeat of organised labour he went to such great lengths to engineer. In the end ‘Tebbit’s Law’ cost me and my fellow NGA members our jobs at the paper. I got by in time. But the point is this: at least he felt the need to watch it, as did enough people to get it repeated on BBC1.

As Tony Benn reminded us, there is no final victory or final defeat, just the same battles fought over and over again. Boys From the Blackstuff tells the story of battles lost, but it remains an example of drama’s, and specifically television’s, power to move and transform, and to present the viewer with versions of the world they may not wish to recognise, or may not have known existed at all.

And that, in the end, has to be a battle won.

Join Revolution! May Day weekender in London

The world is changing fast. From tariffs and trade wars to the continuing genocide in Gaza to Starmer’s austerity 2.0.

Revolution! on Saturday 3 – Sunday 4 May brings together leading activists and authors to discuss the key questions of the moment and chart a strategy for the left.