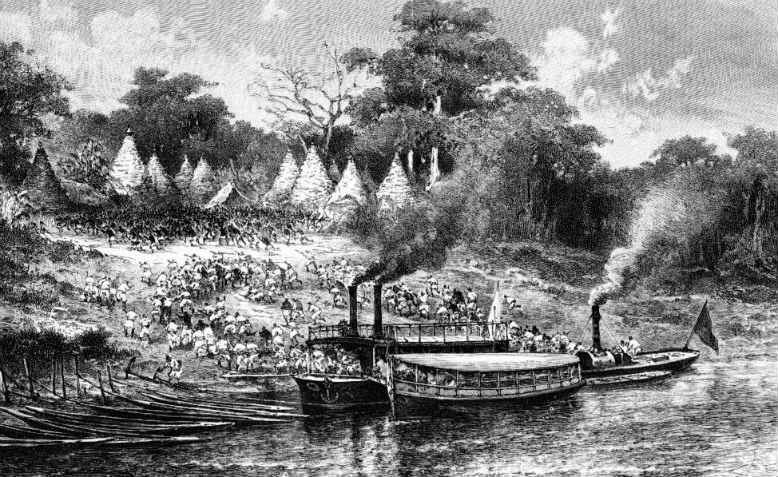

Yambuya, Congo, 1890. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Yambuya, Congo, 1890. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Conrad’s portrait of imperialism in turn-of-the-century Congo has much resonance for the contemporary reader, argues Floyd Codlin

Heart of Darkness (1899) by Joseph Conrad is a novella about a voyage up the Congo River into the Congo Free State in the heart of Africa. Many of us have seen of course the 1979 film Apocalypse Now, which based itself in part on the book.

“Don’t Get off the Boat”

Charles Marlow, the narrator, tells his story to friends aboard a boat anchored on the River Thames. This setting provides the frame for Marlow’s story of his obsession with the ivory trader Kurtz, which enables Conrad to create a parallel between what Conrad calls “the greatest town on earth”, London, and Africa as places of darkness.

Central to Conrad’s work is the idea that there is little difference between so-called civilised people and those described as savages; Heart of Darkness therefore raises questions about imperialism and racism.

What’s also interesting here regarding the novel is that it’s the first time in English literature that we see what we now call an NGO, in this case the imagined “International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs”, being shown as an agent for avarice and imperialism. Kurtz is described as “a prodigy” and “an emissary of pity, and science, and progress'”, representing the “higher intelligence, wide sympathies, a singleness of purpose” needed for the cause of Europe.

In order to get ivory out, while claiming to be there to stamp out slavery, the most brutal methods are used and justified, and it is here that we see a literal clash of civilisations. Conrad is also brilliant at visceral descriptions; you can almost smell the jungle, the smoke from the steamer, the stench of sweat from the chained workers/slaves Marlowe comes across.

To this extent, it punctures one of the myths of imperialist race theory. But, as the critic Patrick Brantlinger has argued, it also portrays Congolese villagers as primitiveness personified, inhabitants of a land that time forgot. Kurtz is shown as the ultimate proof of this “kinship” between enlightened Europeans and the “savages” they are supposed to be civilising.

“The Horror…The Horror”

The novel has become (though no doubt this was not its author’s original intention) a cypher and a useful explanation for more contemporary politics and strands in society, such as: racist anxieties about immigration; the idea that certain places and peoples are primitive, exotic, and dangerous. For contemporary readers and writers, these questions have become an unavoidable part of Conrad’s legacy, too.

During the second half of the 19th century, spurious theories of racial superiority were used to legitimate empire building, justifying European rule over native populations in places where they had no other obvious right to be. Marlow, however, is too cynical to accept this convenient fiction. The “conquest of the earth”, he says, was not the manifest destiny of European peoples; rather, it simply meant “the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves.” Heart of Darkness suggests that Europeans are not essentially more highly evolved or enlightened than the people whose territories they invade.

Caryl Phillips, in an interview for the Guardian with Chinua Achebe, father of modern African literature, noted however the latter’s displeasure with Heart of Darkness: ’Achebe’s lecture quickly establishes his belief that Conrad deliberately sets Africa up as “the other world” so that he might examine Europe. According to Achebe, Africa is presented to the reader as “the antithesis of Europe and therefore of civilisation, a place where man’s vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality”‘.

Achebe sees Conrad mocking both the African landscape and the African people. The story begins on the “good” River Thames, which, in the past, “has been one of the dark places of the earth”. The story soon takes us to the “bad” River Congo, presently one of those “dark places”. It is a body of water upon which the steamer toils “along slowly on the edge of a black and incomprehensible frenzy”. According to Achebe, Conrad’s long and famously hypnotically sentences are mere” trickery”, designed to induce a hypnotic stupor in the reader.”

“Exterminate all the brutes!”

Conrad’s Kurtz also channels turn-of-the-century anxieties about mass media and mass politics. One of Kurtz’s defining qualities in the novel is “eloquence”: Marlow refers to him repeatedly as “A voice!” and his report on “Savage Customs” is written in a rhetorical, highfalutin style, short on practical details but long on sonorous abstractions. Marlow never discovers Kurtz’s real “profession”, but he gets the impression that he was somehow connected with the press — either a “journalist who could paint” or a “painter who wrote for the papers”.

If Kurtz’s “colleague” is to be believed, moreover, his peculiar gifts might also have found an outlet in populist politics: “He would have been a splendid leader of an extreme party.” Had he returned to Europe, that is, the same faculty that enabled Kurtz to impose his mad will on the tribes people of the upper Congo might have found a wider audience.

Politically, Conrad tended to be on the right, and this image of Kurtz as an extremist demagogue expresses a habitual pessimism about mass democracy—in 1899, still a relatively recent phenomenon. Nonetheless, in the light of the totalitarian regimes that emerged in Italy, Germany and Russia after 1918, Kurtz’s combination of irresistible charisma with megalomaniacal brutality seems prescient.

It is from this point of view that Heart of Darkness seems necessary, even inevitable, the product of dark historical energies, which continue to shape our contemporary world.

As well as being a great writer of literature, had Conrad still been living now, then from using the internet, the current political condition of the Congo would not have surprised him.

For the people of the region itself, still subject to the ravages of capitalism, the pith helmet of colonialism has been replaced by the smooth, sleek, discrete imperialism of the IMF, Dow Jones index and the iPad. The various proxy wars and local militia genocides, funded and armed by various governments, have no problem with the order “exterminate all of the brutes”