Photo: Curve Magazine

Photo: Curve Magazine

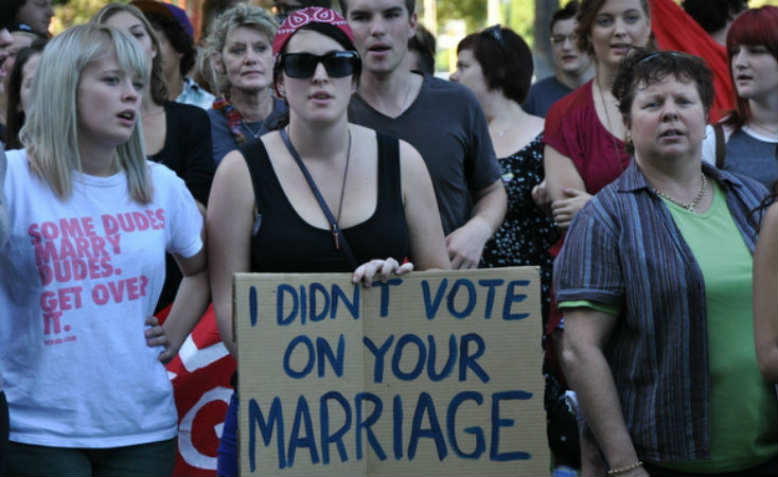

Progressives have lessons to learn from the campaign, not least that when opportunities arise, the public debate ground must be seized

Australia recently joined the international push to remove discrimination of same-sex relationships in its marriage law. A 13-year campaign for marriage equality culminated in the current Coalition government (an alliance between The Nationals, a right-wing conservative agricultural/regional party, and the neoliberal Liberal Party) backing a voluntary, non-binding postal plebiscite. Plebiscites are used to gauge public opinion on issues that do not affect the constitution. To a frustrated population, this looked like a stalling tactic to halt momentum in the campaign, driven by the conservatives in government. Less confidently identified, was that the plebiscite emerged from a destabilising and ongoing tension within the Liberal Party’s ranks, with Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s ‘moderates’ desperate for a win to sure up his unstable leadership.

The opposition Australian Labor Party (ALP), a traditional social democratic party with a decades-long embrace of economic rationalism, focused on exposing the Coalition’s divisions, opposing the plebiscite from the outset as expensive and divisive. Unfortunately, this defensive position was largely adopted by the Yes campaign and as such, it failed to place any pressure on the ALP’s short-term opportunism. After a slow start out of the gates, the Yes campaign was successful with 7.8 million votes (61.6% of all responses) over the No’s 4.9 million (38.4%)— a result that reflected approximately the same support demonstrated in years of polling on the issue.

To build a strong and independent movement for political, economic and social change, progressives must become serious about organisational strategies and the outcomes reached of organising efforts. Australia’s marriage equality campaign is a good start as the first long-term campaign to break our people-moving malaise, reaching the national agenda. While we need to celebrate wins, in the spirit of owning our strategies we must recognise organisational efforts also fell short.

This piece considers what happened when Australia’s marriage equality campaign breached mainstream political debate and how it emerged out of the national plebiscite. It considers what the plebiscite revealed about the state of independent organisation and its ideas base in Australia. It considers (1) how an anti-plebiscite position was a compromised one, and reflected a lack of confidence in mobilising people, particularly youth who were transformed from protagonists to victims throughout the campaign; (2) the dominant role played by a politics of scarcity (i.e. in a time with finite resources, the plebiscite should be opposed because it is expensive); and (3) how the campaign sparked some positive developments in union organisation.

Anti-plebiscite?

Once the plebiscite was announced, it became commonplace for the marriage equality campaign to claim the ‘job’ should really ‘just be done’ by politicians through parliamentary vote. This position, adopted from the ALP, denied the years of crisis in policy and in authority within our political institutions that led to people taking the reins and building the campaign from the outset. For instance, Senator Wong, who emerged a key leadership figure for ALP throughout the plebiscite held the party line for traditional marriage when in government in 2010. Previous ALP Prime Minister, Julia Gillard also spoke publicly after her prime ministership about why an anti-gay marriage position was justified because she didn’t think the institution of marriage was for her (and dressed it up as a pro-woman position). And to clarify, the point of outlining the limiting role the ALP played on the capacity of the marriage equality campaign is not to expose them as failures of leadership (I don’t expect the ALP to lead); it is to demonstrate the relationship of the party apparatus to organisational efforts by everyday people. Without legitimate renewed activity in peoples’ organisation, the apparatus isn’t pushed by social pressure to play a more radical role. As such, retro-fitting the marriage equality campaign into the ALP’s anti-plebiscite position, rather than forcing them to come to us, limited ability to respond to bigger issues of LGBTI rights.

Instead, the dominant line emerged that the plebiscite constituted a vote on the rights of a minority group that would create a ‘dangerous precedent’. This framing negated Australia’s long history of mass movements for civil rights and the role of democratic process in changing legislation. How did this negation manifest? It looked like ACT MP Andrew Leigh (ALP) at Canberra’s rally lamenting the position LGBTI people had been put in, when no other group throughout Australian history had been ‘subjected’ to a national vote on their status. And these words rang out to a sea of defiantly nodding protestors. Nevermind that national referendum in 1967, where predominantly white Australia voted on whether Aboriginal people would be considered constitutionally part of the nation—a campaign that came to represent broad demands for rights and respect for indigenous people. And while Leigh’s framing is a knee-jerk reaction to a Coalition position (no-brainer politics at a time where most Australians are dissatisfied with the government), what is being denied is the work of masses of people taking action to make steps forward for minority groups and all working people.

Ultimately anti-plebiscite positions adopted by the Yes campaign reflected fear of participation by everyday Australians. And this showed a deep distrust in people—a distrust that, at a time where the void between the political class and the experiences and aspirations of working people grows, is far more dangerous to our cause than the religious conservative right.

Youth: from protagonists to victims

What happened to youth in the campaign reflects how a lack of confidence shot us in the foot. In a spectacular protagonist role reversal, young people sitting in high schools flipped from campaign leaders to defenceless victims of national debate. The media coverage was everywhere lamenting the great harm inflicted on our youth. And this victimisation was embraced by the Yes campaign as it attempted to adopt the moral high-ground over the Coalition who were ‘subjecting’ our poor youth to the viciousness of public debate.

What ensued were attempts to out-moralise the right on who was the best protector of young people. One of the worst outcomes of adopting this position was that it closed off an ability to broaden the campaign to issues of gender and sexuality socialisation, the ground for which I think was well established in the battle to establish the Safe Schools program and keep it afloat. Adopting a ‘defenceless children’ position played directly into the conservatives’ hands and their years-long campaign attacking the Safe Schools program (and left-wing activists behind the program’s establishment).

Then there is the issue of taking the power away from youth as active leaders of the campaign. By proclaiming a group as victims, we also make it so. This victimisation was a great failure of the Yes campaign. To the gay teenager sitting in high school, questioning his identity and contribution to this moment of societal change, the Yes campaign told him he was already a victim, needing of protection from political debate and outside of the process of social change. Ironically, this was exactly the tactic adopted by the conservatives to take the steam out of the campaign, restricting the survey to those only on the electoral roll, undermining the participation of youth not of voting age.

The campaign had a responsibility to challenge the victim narrative, reach out to vulnerable youth and empower them to join the fight—not tell them to sit back and wait while others campaigned for their future rights to enter into a contract of marriage. Failure to broaden the campaign reflected both a lack of confidence in youth and a blindness to their abilities. The original fire and great potential of this campaign came from politically disaffected youth who fought under both ALP and Coalition governments. Their power was integral in this national debate. Younger generations have made significant contributions to big campaigns throughout Australian history, such as the high school walkout against the Vietnam War. While the scale of public organisation and momentum for the plebiscite was clearly not comparable to this period, any national campaign is an opportunity to empower the next generation of leaders and should be taken seriously.

Defeatism, moralism and ALP short-terminism

The Yes campaign was unable to fully break from the ALP and articulate an expanded agenda for LGBTI rights. Instead of politics, the campaign became about process. Being anti-plebiscite was a moral position of protecting vulnerable victims from a democratic process. The ensuing defeatism was paraded throughout the campaign, with people decrying that it was a gross stalling tactic that would hurt people. Even in victory, the story was one of needing to heal in the aftermath, rather than confidence from the win encouraging us to keep building the fightback against the government and its assault on everyday people.

Screenshots of far-right No material were shared widely across Facebook, with a corresponding outcry that Turnbull had *LIED TO US* about this being a respectful debate. In a context where the majority of Australians were in a position to recognise the vile homophobic content of the No’s campaign, of what use was giving them more space for their ideas? Of what use is moralistic outrage more generally? Many know that far-right and religious conservative forces exist and they were always going to come out of the woodwork, well-funded and well-organised. It was our duty to embolden and activate the majority of Australians already on our side.

Austerity economics – transcending ideas that limit us

For decades, the Australian political establishment have told us that that we must accept cuts to our own living conditions to be competitive in the world arena and to tackle future post-GFC slumps. To a people struggling under the weight of decades of erosion in their social programs, the case that the plebiscite should be opposed because it was too expensive resonated. The logic followed that $122 million was money that would be better placed in our struggling health and education sectors, or put into restoring cuts government made to funding for Aboriginal legal aid or women’s shelters. This position demonstrated a lack of understanding among people of the scale of resources available to political interests when in control of the public purse, and a tacit acceptance of the logic of the neoliberal agenda that has been white-anting our social services for decades.

Building public understanding of what kind of economy and society we want is important. However, the question is whether this confident and independent politics was fostered within the anti-plebiscite campaign strategy. And it wasn’t. In the absence of this confidence, the assumption that cuts to our services are made due to insufficient funding—that times are tough and the people have to accept an era of belt-tightening— was never overcome.

In reality, the resources available to government are immense. What government funds reflects political choices. This is why billions flow into defence, offshore detention centres and corporate tax cuts, but the war on States’ public healthcare funding is an absolute necessity! Governments have made political choices to dismantle the services and institutions that support working people. Not because funding is tight, but because a weakened and divided working population without its latticework of support means cheaper, more exploitable labour for big business, and because every million freed up is a million that can be diverted to handshake deals with the governments’ friends (working people are not their friends). Rolling back public funding for services also create markets for the private sector. By accepting a politics of scarcity, we accept the same weapon used against us.

While the plebiscite was not a process designed to maximise participation by all people, opposing it based on its cost was wrong. In a time where the crisis and depravity of mainstream politics is leading young people to conclude that technocratic non-democratic models of governance might be preferable, progressives should never seek to rationalise democratic processes based on cost. Democracy is expensive! For instance, elections cost a lot to run; the cost of the 2016 federal election was estimated at $227 million, and expected to increase to $300 million in 2021.

We must transcend the politics of scarcity and build popular confidence about how people can drive the economy in our interests. And part of stepping out confidently is recognising and embracing the costs of democracy since in our efforts to build a more participatory, equal society, democracy will become costlier in terms of resources and labour time from our collective efforts.

The role of unions – some good signs

To finish on an organisational positive, one of the strongest developments from the plebiscite was unions’ willingness to get behind the campaign, and take on the debate about the role of union in broader social campaigns. In a time where unions have pigeon-holed themselves into income insurer roles, it was a big and important step to articulate a vision for unions beyond wages and conditions protectors.

Where blue collar unions would have been expected to be tailgaters on this campaign, due to the particular challenges of confronting institutionalised homophobia in their sectors (conservative underpinnings of the breadwinner working male model), they were actually the trailblazers. They were the most confident in taking on the debate among membership for why campaigns for equality are the business of unions and how division between workers have negative impacts on all of us. This impressive leadership should not go unnoticed and brings home the lesson that strong, militant unions that promote active membership are best equipped to take on the battles. As such, the work is set out for us in building fighting democratic structures within white collar industries, which employ the majority of working Australians.

Conclusion

Any future steps forward for everyday people in our current political climate will depend on our ability to drive strategies independent of status quo institutions, and drive change that can place pressure on the political establishment. In the case of the Yes case for marriage equality, focus on expanding the grassroots nature of the campaign and mobilising as many people as possible was displaced due to an inability to carve an independent line from the ALP. Instead, Yes spent a great deal of time opposing a process ‘forced’ upon the community and this defeatism plagued the campaign.

It is important to recognise that politics is never about navigating the grounds in which we choose. It was wrong to oppose the plebiscite. This was a popular issue for which the ground had been largely fought through decades of campaigning. The equal marriage plebiscite was clearly winnable, with polls showing the majority of the public had been in support of change for years. Resourcing was being provided to campaign on something winnable, and an opportunity handed to build momentum for a renewed period of political activity.

At a time where the majority of Australian people are going materially backwards, but are disparate, non-unionised and unorganised, the message of weeding out divisions among us to unite is the main game. The plebiscite opened some space for rank and file debate within their own bureaucratic union constraints and this was a good step forward. However, when future opportunities for mass participation open up, progressives must resist opportunistic drag from the political class and confidently claim the public debate ground. The plebiscite also revealed the scourge of austerity logic among working people, which will need to be challenged in coming activity.