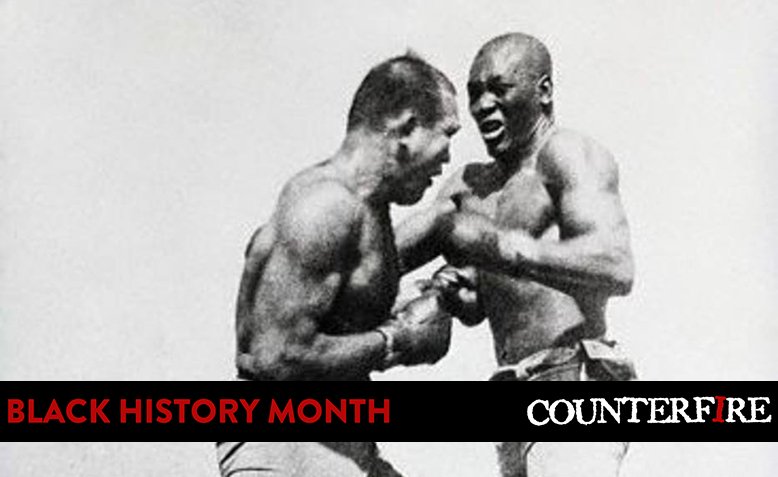

Jack Johnson fights James J Jeffries, 1910. Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Jack Johnson fights James J Jeffries, 1910. Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Imperialist and racist tactics were used to attempt to ensure both literal and symbolic white dominance of the sport, argues Gavin Lewis

Over the summer of 2020 as the statues of historical racists were torn down by UK activists, right-wing politicians claimed that instead of pulling them down, such representations should be given ‘context’.

Perhaps heeding this advice, the following September, pastor’s son and Extinction Rebellion activist Benjamin Clark daubed the word ‘racist’ on a statue of Winston Churchill. Yet regardless of ‘context’, he was fined £1,642.03 for the offence.

Churchill was known for his ‘dog in the manger’ racism towards indigenous peoples.[1] As well as this, in 1911 as Home Secretary, Churchill racially segregated British boxing. In the next decade, one of the victims of this ban on inter-racial fights was Manchester’s Black, popular fairground booth fighter, Len Johnson.

Hugh Cecil Lowther (Lord Lonsdale) of the National Sporting Club clearly wanted to take no public credit for the ban, because he laid the blame entirely at Churchill’s door. He told Empire News how the legality of boxing was made conditional on having no ‘inter-coloured contests’ following talks with Winston Churchill at the Home Office.

Expressing his distance from the decision Lord Lonsdale wrote of Johnson:

“I am very sorry, because he is a very fine fellow, a really nice man with a splendid personality and a splendid boxer. But there it is.”

It was finally around 1946 when the first Black fighter – Dick Turpin, older brother of future World Middleweight champion Randolph Turpin – was allowed to compete for a British title.

This begs the question: what was the ideological purpose of segregating boxing? Sport sociologist John Hargreaves has suggested:

“sport is seen as inculcating and expressing the quintessential ideology in capitalist society: egoistic, aggressive individualism, ruthless competition, the myth of equality of opportunity, together with authoritarianism, elitism, chauvinism, sexism, militarism and imperialism.”[2]

In simple terms, sport justifies inequality, free market and imperialist competition, via a simplistic notion of supposed meritocratic survival-of-the-fittest supremacy. For Winston Churchill, white western elites had empire because they were “a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a more worldly-wise race”.[3]

Clearly, the racist ideology that Churchill encapsulates would be thrown into crisis if a Black child of slavery and empire came back and were to beat in combat competition a representative of Churchill’s so-called ‘stronger, higher-grade, more worldly-wise race’.

The September 1980, the World Middleweight title fight between champion Britain’s Alan Minter and Black US fighter Marvin Hagler was indicative of the continued resonance of the Churchill-type ideology of racial national supremacy, and the collective psychosis generated when it’s thrown into question. Minter as an amateur had been in British teams such as the UK 1972 Olympic boxing squad, and when interacting with others internationally, had shown no previous signs of prejudice.

But perhaps indicative of the symbolic position he now occupied and, reflecting the sentiments of his current group of supporters prior to the fight, bizarrely stated “no black man is going to take my title”.

He followed this by entering the ring “behind a union flag and St George’s cross” (the St George cross was at that time an emblem also used by the racist National Front). For the deluded, he was now the fighting spirit of white England. When he lost convincingly, rabidly angry ‘fans’ distraught at having their world view violated, pelted Hagler with coins and bottles, and the venue experienced the worst rioting ever televised at a British boxing event.

These scenes though were not as entirely historically new as contemporary commentators suggested. Tom Cribb was England’s bare-knuckle champion in the early 19th century. He similarly was regarded as the epitome of the traditional English ‘milling’ yeoman – representative of the fighting backbone of its empire.

When Cribb had difficulties against Black competitor Tom Molineaux, Cribb’s angry fans forcibly entered the ring. In the resulting melee the Black challenger ended up with a broken finger.

Former World Heavyweight champion American John L Sullivan used to publicly proclaim, “I can lick any son-of-a-bitch in the world.” As the largest fighting division, during Sullivan’s era and long after, America regarded the World Heavyweight title as its most significant symbolic representation of patriarchal dominance.

This was no problem in an era when those contesting the title were usually almost always American and exclusively white, because this fitted a particular view of an emerging unstoppable, national identity, not dissimilar to the sentiments Churchill articulated.

In 1908, African-American Jack Johnson gained the World title, and it is interesting to speculate if this influenced Churchill’s ban on Black boxing success three years later in 1911. Because this caused a rupture in the notion of white American material ascendancy and the backlash was consequently enormous.

Johnson smiled when beating white opponents, had sex with a string of white girlfriends and others, plus in terms of his blatant hedonism, was an affront to traditional bourgeois capitalist notions of lives and finances lived based upon ‘deferred gratification’.

Galling for mainstream America, Johnson did all this while the country was being force-fed an ideology demanding an adherence to white ‘Protestant Work Ethic’ norms. Johnson’s affront to the racist and conformist status quo was so severe that Federal authorities colluded in persecuting him on faked trafficking charges under the Mann Act, forcing him into a dubious title defence bout which he lost.

American Marxist critic Mike Marqusee noted “No black fighter was given a shot at the title for twenty-two years after Johnson lost it.” [4] If segregation hadn’t been enough of a problem before Johnson, essentially after, in blocking Black athletes’ access to World Heavyweight title fights, there was now a covert tactic of also reasserting it in micro-policy, in order to preserve a particular hierarchy of power and identities.

Mike Marqusee observed:

“When Joe Louis emerged in the early thirties, his handlers were determined to learn from Johnson’s bitter experience. Louis was given lesson in table manners and elocution; he was told to go for a knockout rather than risk the whims of racist judges; he was told never to smile when he beat a white man and, above all, never to be caught alone with a white woman.” [5]

Subsequent successful Black heavyweight fighters were in the manner of Joe Louis and Floyd Patterson, either disciplined and groomed into establishment safe identities or like champion Sonny Liston treated as ferocious, yet domesticated, animalistic pets.

When Cassius Clay defeated Liston, won the title and via conversion to the Nation of Islam, took the name Muhammad Ali, we were again back in transgressive Jack Johnson-type territory. Followers of the Nation of Islam reacted to years of slavery, post-slavery disenfranchisement, lynching, and anti-miscegenation laws, by defining their white oppressor as the devil.

Consequently, in the absence of competent white fighters, the US establishment reacted by using conformist or non-political Black fighters as symbolic white racial surrogates. Floyd Patterson fitted the bill when he vowed unsuccessfully to bring the title back to Christian America. Apparently politically unaware fighter Ernie Terrell using Ali’s slave name was also allocated the same symbolic position.

Ali’s eventual statement in refusing to fight in the Vietnam war meant that he’d connected domestic anti-racism with anti-imperialism:

“Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?

No, I am not going ten thousand miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when such evils must come to an end.… But I have said it once and I will say it again. The real enemy of my people is right here”

Consequently, US Federal policy attempted to penalise him by banning him from boxing and establishment narratives similarly attempted to reduce and tame his symbolic significance.

US public relations suggested he was not really that good in comparison to former white champion Rocky Marciano and a faked computer fight was staged. Joe Frazier, who’d become champion in Ali’s absence, was allocated the new undeserved current role of competing white racial surrogate – sometimes labelled the ‘Black Marciano’.

Even when Ali had regained his title and restored his reputation, his achievements like the performed Marciano fight, and Frazier Superfights[6], would be re-inscribed into white establishment successes in the form of Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky franchise series.

Stallone would become a fake white boxing champion just as non-military serving John Wayne was previously made a fake war hero. If there could not be literal racial segregation then a symbolic exclusion and reallocation of Ali’s transgressive characteristics would take place.

It’s worth noting that these issues of literal and symbolic segregation persist into the modern era. The eccentricities of Super Middle Weight Champion Chris Eubank rarely intruded into his fight career. However, when in retirement he, like Ali, actively questioned the invading Iraq/Afghanistan new imperialism of our era, then the ‘loony celebrity’ trope was fielded against him by the corporate media.

[1] Churchill on Palestine and western colonialism: “I do not agree that the dog in a manger has the final right to the manger even though he may have lain there for a very long time. I do not admit that right. I do not admit for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a more worldly wise race to put it that way, has come in and taken their place.”

[2] John Hargreaves (1982) Sport, Culture and Ideology. P41-42 Chapter 2 Sport, Culture and Ideology. Edited by Jennifer Hargreaves.

[3]Ibid, Churchill on Palestine and western colonialism

[4] Mike Marqusee (1999) Redemption Song: Muhammad Ali and the Spirit of the Sixties. P24.

[5] P24 Ibid.

[6] While this term was in use for this series of three fights, the more common expression was ‘Fight(s) of the Century’, particularly to refer to the first one in 1971, which was correctly billed as a match-up between two unbeaten champions.

Before you go

Counterfire is growing faster than ever before

We need to raise £20,000 as we are having to expand operations. We are moving to a bigger, better central office, upping our print run and distribution, buying a new printer, new computers and employing more staff.