Keenie Meenie exposes, with thorough research, the activities of a booming, highly lucrative outsourced industry, and its intimate ties with the British State, finds Susan Ram

Times are bright for Britain’s private military and security sector. For companies operating in this lucrative arena, there are rich killings (both monetary and literal) to be made in multiple corners of a volatile, conflict-riven world. State largesse is available in plenty, unaccountability is written into the script, and governmental nods and winks ensure that this outsourced industry encounters few constraints beyond limp, pro forma calls for ‘self-regulation’.

Heading the pack of twenty-first-century privateers is the UK multinational G4S. This is the world’s largest private-security company, with a £500 million annual turnover in Africa and multimillion pound contracts to provide security in Iraq and Afghanistan. Then there’s the intriguing concentration of ‘guns for hire’ enterprises around the cathedral city of Hereford: fourteen at the last count.

No real surprise there, given the city’s proximity to the headquarters of the Special Armed Services (SAS): the source of recruits for what War on Want estimates to be at least 46 separate companies, their contracts running into billions of pounds. The big names include Aegis Defence Services (now part of GardaWorld), Control Risks and Olive Group, their senior executives and boards dominated by former military officers: a recent CEO of Aegis was none other than General Graham Binns, former commander of British troops in Basra.

In 2016, War on Want described Britain as the ‘mercenary kingpin’ of a global private military industry. ‘Private military contractors ran amok in Iraq and Afghanistan, leaving a trail of human rights abuses in their wake,’ noted John Hilary, the charity’s executive director. ‘Now we are seeing the alarming rise of mercenaries fighting on the frontline in conflict zones across the world: it is the return of the “dogs of war” … For too long this murky world of guns for hire has been allowed to grow unchecked’ (Quoted by Richard Norton-Taylor, ‘Britain is at centre of global mercenary industry, says charity’, The Guardian, 3 Feb 2016).

A deadly export industry

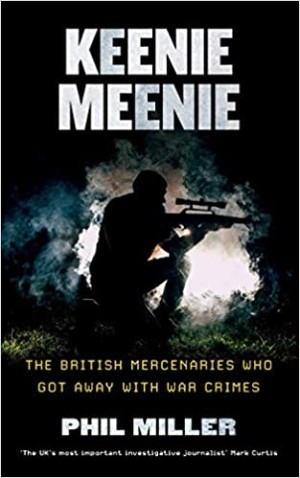

Attempts to penetrate this ‘murky world’ have to contend not only with the secrecy with which the industry cloaks itself but also with official obstruction at every level. Yet, as the investigative journalist Phil Miller shows in a compelling and accessible new book, there are resources in semi-plain sight that can be tapped and put to work towards exposing an industry awash with blood and steeped in criminality.

For Miller, an investigator for Corporate Watch and Reprieve, now working as a staff reporter for Declassified UK, much can be gained by returning to that unromantic staple of the historian’s trade: ferreting through the archives. His book testifies to the usefulness of travelling to Kew to undertake systematic explorations of recently declassified files at the National Archives. While such work at the coalface can be slow and laborious, nothing quite beats the thrill of coming face to face with memos and documents that have been off-limits for the past thirty years. For those on the track of a specific story, there are moments when the significance of a hitherto secret cable or redacted passage simply leaps off the page.

The story that kept taking Miller back to Kew was that of a company called Keenie Meenie Services (KMS), an early exemplar of privatised, for-profit ‘security’ provision and in many respects the template for an emergent industry. Despite its arcane name (‘keenie meenie’ is thought to be SAS jargon, although opinions differ), the company succeeded in attracting zero public scrutiny from its founding in 1975 until it shed its skin to assume a fresh identity, Saladin Security, in the 1990s.

There is much ingenuity in the way Miller tackles the task of telling the KMS story. Multiple challenges presented themselves. How to hook twenty-first-century readers onto distant events and struggles from the 1970s and 80s? How to keep those readers on side through the book’s maze of detail and cross-continental shifts of scene? How to balance academic thoroughness with narrative tricks of the trade aimed at keeping readers on track?

One solution has been to make this a multimedia venture: the book has a companion documentary film, due for release later this year (a trailer is available online). This cinematic dimension reappears in the second strand of Miller’s strategy: use of the thriller genre. From its opening lines, the book engages core elements of the page-turner: brisk pacing; memorable locations colourfully evoked; an intriguing cast of characters; twists of plot; and spine-chilling episodes of violence. There is a hybrid quality to the results: while at one level the book seems geared to paying back pro-mercenary thriller writers like Frederick Forsyth in their own coin, it is also indisputably a serious piece of research, carefully put together and backed by extensive footnotes and references.

Like many a thriller, the book establishes a strong story line, which is pursued chronologically. Chapter titles, catchy and intriguing – ‘White Sultan of Oman’; ‘The Upside Down Jeep’; ‘Grenades in Wine Glasses’; ‘Bugger Off My Land!’ – set the pace. As the narrative builds, readers are alerted to the widening geographical scope of KMS operations, from its initial activities in Oman in the 1970s to its interventions in Nicaragua (aiding the Contras), Sri Lanka (buttressing Colombo’s anti-Tamil war by providing counterinsurgency training and more), and Afghanistan, where the company is shown to have played a key role in building the jihadi offensive of the late 1980s.

KMS, the British state, and war crimes

At least three key aspects emerge from Miller’s piecing together of the KMS story. Firstly, the book tracks the company’s progression from security provision to its altogether more hands-on role in the management, conduct and direction of conflicts. The second aspect is the light thrown on the nature and consequences of KMS covert operations: specifically, the company’s complicity in war crimes carried out in its various operational theatres.

Thirdly, Miller offers strong documentary proof, in some cases backed by witness testimony, that at every stage KMS conducted its affairs with the knowledge and connivance of the British state. The Foreign Office players, who speak candidly from the files and cables Miller brings to the clear light of day, establish the state’s eagerness to make adroit use of its clandestine warriors in its global game-playing. After all, ‘plausible deniability’ could always be invoked.

For this reviewer, there’s a particular poignancy to the book’s account of Keenie Meenie’s activities in Sri Lanka during a crucial phase of the Tamil ethnic struggle. During the 1980s, state suppression of the island’s Tamil minority intensified to the point where pogroms and naked terror forced thousands into exile, reinforcing Tamil demands for a separate state. At the time, I was living in Chennai, across the Palk Strait in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. As a freelance journalist covering the story, I met quite a number of the players who appear in Miller’s book. I got close to Tamil political veterans who had found sanctuary in Chennai, and learnt much from their meticulous first-hand accounts of the evolution of the struggle. On trips to Colombo, the Sri Lankan capital, I also met leaders on the opposite side: President J.R. Jayewardene, for one – the sly old fox who slinks in and out of Miller’s narrative – and also his muscular national-security minister, Lalith Athulathmudali, a particularly hawkish exponent of counter-insurgency, Sri Lankan style.

Imperialism, atrocity and Sri Lanka

At the time there was little evidence of Western involvement in what appeared to be a purely local conflict (albeit one with important implications for India and other regional players). However, among Tamil militant groups, occasional rumours pointed to the presence of white fighters among Sri Lankan army and police contingents. It was a report to this effect, passed on to Miller by a London-based former militant in 2011, which prompted him to dig deeper.

Miller was able to obtain eye-witness testimony from a young woman in northern Sri Lanka (the Tamil-majority portion of the island) who recalled the army’s arrival in her village back in 1985. Among the helicopter pilots who landed was ‘a tall white man who was watching everything carefully. Many other people in my village saw him that day … Villagers later referred to him as Mossadu … Later I learnt that Mossadu are overseas white men’ (p.1). The soldiers proceeded to tear the village apart. They shot sixteen residents dead, left a further thirty gravely injured, and set more than seventy homes ablaze. An entire community was destroyed: one of hundreds to be erased in the course of the conflict.

Secret British government cables, finally declassified three decades later and now cited by Miller, support the woman’s claim that a white pilot took part in the atrocity. In one cable, dated 20 November 1985, a diplomat reveals that a mercenary company, KMS:

‘appear to be becoming more and more closely involved in the conflict and we believe that it is only a matter of time before they assume some form of combat role … Members of KMS are frequently seen both at hotel bars in Colombo and at private functions, the identities of many of them (and of the role of the team as a whole) are well known to the British community here’ (p.4).

In fact, KMS was busy setting up Sri Lanka’s Special Task Force (STF), an elite paramilitary police unit specialising in counterinsurgency warfare. All was modelled on the SAS, down to the design of the unit’s training camp: in essence a replica of Credenhill, the SAS headquarters outside Hereford. The remit was to transform a hitherto lacklustre armed police body into a killing machine imbued with SAS efficiency and ruthlessness and fired up by extreme anti-Tamil racism. ‘Every twelve weeks, KMS promised to churn out a new company of 120 police commandos, drawn from the Sinhalese community,’ notes Miller. ‘The counter-insurgency blueprint repeatedly recommended by British advisers … was finally being implemented … without Whitehall having to be directly involved’ (p.108).

The STF soon became a byword for terror and atrocity, a specialist in massacring civilians and laying waste the land. There’s a case to be made that its creation, at a crucial moment in Sri Lanka’s ethnic struggle, when peace talks were being mooted in the context of a military stalemate, helped set in motion the train of events that led to the bloodbath ending of the civil war in 2009. To this day, no one can give a precise figure for the number of Tamils slaughtered.

During an interview with Aaron Bastani, back in February 2020, Miller set his investigation of KMS in a broader context: that of the urgent need for critical research on British foreign policy. Since then, the toppling of statues, the reappraisal of Churchill and other national heroes’ figures, and other responses to the resurgence of Black Lives Matter have intensified interest in the activities of the British state – and its hush-hush mercenary operatives – on distant shores. Miller’s book, with its companion film, could hardly be more timely.

Before you go

Counterfire is growing faster than ever before

We need to raise £20,000 as we are having to expand operations. We are moving to a bigger, better central office, upping our print run and distribution, buying a new printer, new computers and employing more staff.