The story of Snowden’s whistleblowing reveals the importance of genuinely free journalism, but only mass movements can truly defend civil liberties, argues Peter Stäuber

Sitting in his Hong Kong hotel room in May 2013, Edward Snowden got frustrated: ‘By every standard I could imagine, the hard part was over. But my imagination hadn’t been good enough, because the journalists I’d asked to come meet me weren’t showing up. They kept postponing, giving excuses, apologizing’, he writes in his autobiography, Permanent Record. His impatience is understandable. He had taken an enormous risk, copying highly classified material, smuggling it out of his workplace, then out of the country, and reaching out to potential allies that would help him publish the documents. But if the journalists he had contacted didn’t play their part, all would have been for nothing.

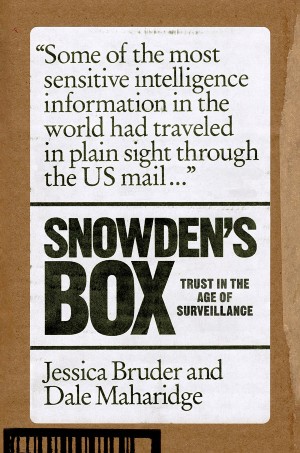

In their short book, Snowden’s Box, Jessica Bruder and Dale Maharidge shed light on the opposite side of the story; the Snowden leak from the perspective of some of the journalists involved. Unlike Laura Poitras and Glenn Greenwald, who took centre-stage in the Snowden leak, Bruder and Maharidge only played a small part in the ‘impromptu network that helped Snowden,’ as they put it (p.10). It consisted of receiving a package in the post, the contents of which they were ignorant about.

Maharidge, an investigative journalist who teaches at Columbia Journalist School in New York, got caught up in the Snowden saga through his relationship with Laura Poitras, the documentary filmmaker who Snowden chose as his contact. In January 2013 Poitras wrote in her journal: ‘Just received an email from a potential source in the intelligence community. Is it a trap, is he crazy, or is this something real?’ (p.19). She took her partner Maharidge into her confidence. Over the next few weeks, they talked about the source in a coded language; Poitras’ previous run-ins with the intelligence agencies on account of her documentaries had made her extremely cautious.

Specifically, Poitras wanted her partner’s help in finding an address in the US – something that Snowden had asked her to provide, ‘in case something happens to you or me’ (p.20). Maharidge thought of his friend and colleague Jessica Bruder, who also teaches at Columbia. Bruder agreed to have her address used as a contact point. So, it happened that the first documents about the intelligence agencies’ spying activities – the biggest intelligence leak in the NSA’s history – arrived in a simple parcel placed at the door of Bruder’s Brooklyn apartment.

Challenging the surveillance state

Maharidge and Bruder give the reader an interesting insight into the mind of the journalist involved in a monumental story like the Snowden leaks. Far from being mere conveyors of information, they are crucial players that take high personal risks. By assisting the whistleblower in his efforts they could themselves become subjects of interest for the intelligence agencies, or even make themselves liable for prosecution. It is a reminder that the harsh treatment dished out to whistleblowers during the Obama years, as well as the ever-expanding surveillance state, makes the job of journalists both harder and more dangerous. Even writing the book is not without danger, the authors write: ‘Given how the Trump administration treats journalism as a conspiracy against the government, it could be used as a roadmap to our indictment’ (p.10).

Nonetheless, Bruder and Maharidge rightly point out that ‘once people censor themselves and stop telling stories, the work of the government has already been done’ (p.10). They wanted to publish the story of Snowden’s box as a testament to the ‘power of trust’; the importance of connections between people that defy the logic of the surveillance state. Their claim that trust, shared by a civic-minded community, ‘is the one thing that can keep state power in check,’ and even that ‘trust is the difference between civilization and chaos,’ may seem slightly simplistic.

Surely, if the surveillance state is to be challenged and dismantled, what is needed is a broad mass movement of people who come together for this purpose. There needs to be a wide campaign working towards a common goal, rather than mere instances of personal trust. The liberal notion of civil society can never exist as a sphere of detached neutrality without the organised force of mass movements to challenge the corporate and state powers who would otherwise smother it.

However, as far as the story they tell is concerned, their book is indeed a reminder that the simplest human connections are sometimes vitally important for journalists to carry out their work beyond the gaze of the spying agencies. Bruder and Maharige’s book is a timely reminder of this fact.

Before you go

Counterfire is growing faster than ever before

We need to raise £20,000 as we are having to expand operations. We are moving to a bigger, better central office, upping our print run and distribution, buying a new printer, new computers and employing more staff.