With the feminist movement on the rise, Elaine Graham-Leigh appraises contrasting approaches to challenging sexism and the place of women in today’s system

Laura Bates, Everyday Sexism (Simon & Schuster 2014), 384pp.

Everyday Sexism is the book of the Everyday Sexism project, which encouraged women to submit their stories of the sexist treatment they had experienced. Begun in 2012, it now has over 80,000 entries and has been called ‘one of the most successful social media campaigns of all time’. The submissions cover sexism in all sorts of contexts, but one aspect comes over particularly strongly: the catcalling, abuse and assaults women face from men in public places.

Laura Bates describes in her introduction how it was a week of ‘little pinpricks’ like these which brought her to her own tipping point, where she decided to try to do something about it:

‘the man who appeared as I sat outside a café, seized my hand and refused to let go; the guy who followed me off the bus and lewdly propositioned me all the way to my front door; the man who made a sexual gesture and shouted “I’m looking for a wife” from his car as I walked wearily home after a long day’ (p.11).

Everyday Sexism is not the only project documenting street harassment (see for example Hollaback) but the presentation here both puts it in the context of more general sexist attitudes and brings home just how ubiquitous it is. As Bates herself put it;

‘these events were normal. They hadn’t seemed exceptional enough for me to object to them because they weren’t out of the ordinary. Because this kind of thing was just part of life – or, rather, part of being a woman’ (p.12).

Compiling these testimonies has also allowed Bates to highlight patterns, such as the horrifying levels of abuse aimed at very young women. It is clear that street harassment tends to begin for most women when they are around twelve or thirteen, and there is an entire section here devoted to the abuse experienced by girls in school uniform. This street harassment seems to be from older men, but girls are also experiencing abuse from their male classmates, which many of the reports connect to the easy availability of hard-core porn in which women are portrayed as sex objects. As one teacher reported:

‘I witness on a daily basis the girls in my classes being called “whore”, “bitch”, “slag”, “slut” as a matter of course, heckled if they dare to speak in class, their shirts being forcibly undone and their skirts lifted and held by groups of boys’ (p.105).

What Bates is delineating here, although she does not use the term herself, is rape culture:

‘a complex of beliefs that encourages male sexual aggression and supports violence against women … [where] women perceive a continuum of threatened violence that ranges from sexual remarks to sexual touching to rape itself. A rape culture condones physical and emotional terrorism against women as the norm.’

Part of this is both minimising the abuse as harmless banter – ‘lighten up, can’t you take a joke?’ – and making women themselves responsible for sexual abuse, assault and rape because of the routes they walked, the clothes they wore or what they did or did not say. This is despite the fact that there is clearly no magic word, style of dress or route home to prevent abuse. As demonstrated unfortunately by two cases in the US late last year, both of the most commonly-advised strategies for harassment – ignore it, or make clear it’s unwelcome – can get you killed. Yet judges continue to hold young female rape victims responsible for their rapes (‘She let herself down badly’: A judge at Caernarvon Crown Court in December 2012 to a teenage rape victim), and whole communities can rally round to support the men who gang-raped an eleven-year-old (p.351).

One of the strengths of Everyday Sexism is that along with documenting the abuse women face, it also allows them to share their comebacks, whether in how they report what happened:

‘Drive-by “SLAAAAAG!” from white van man this morning. Speed of vehicle precluded discussion of gender politics’ (p.177);

Or how they responded at the time:

‘Walked past a group of men – one of them started shouting at me: “Whoah! Come on darling!” and whistling, egged on by his friends. Crossed the street, went right up to him and said: “Yes?” He looked really puzzled and the laughter stopped. I said: “Well, you obviously wanted my attention. Here I am – what did you want to say to me?” He looked embarrassed then and sort of turned and shuffled away. I felt like the strongest person in the world’ (p.180).

It is not a project which encourages women to see themselves as passive victims of sexual aggression. However, there is an argument that the theory of rape culture can contribute to precisely that; that in highlighting the dangers women face simply for being female in a public place, it can work against women asserting their right to be there without fear. The penultimate chapter of Everyday Sexism is after all called ‘Women under Threat’. The section on the influence of porn on very young men in particular may be enough to make older feminists at least think that something has changed, that younger women today are at more risk of sexual abuse and violence than their older sisters or their mothers may have been. Or is that simply giving in to a moral panic?

GirlTrouble: Moral Panic?

Carol Dyhouse, Girl Trouble. Panic and Progress in the History of Young Women (Zed Books 2014), viii, 312pp.

Carol Dyhouse’s central argument in Girl Trouble is that throughout the twentieth and into the twenty-first century, advances in women’s freedoms have been accompanied by dire warnings by ‘experts’ that young women were at risk, morally and/or from mistreatment by predatory men. ‘Waves of anxiety, horror stories and panic, then, have accompanied social change affecting women since Victorian times … There has been a recurrent tension between a feminist tendency to portray women and girls as victims and a counterbalancing insistence on women’s agency and capacity for self-determination’ (pp.250-3).

She traces the ways in which young women’s freedom has been made into a problem, from the flappers of the post-First World War period, ‘“the frivolous, scantily-clad, jazzing flapper, irresponsible and undisciplined, to whom a dance, a new hat or a man with a car” was irresistible’ (p.78) to the ‘shameless little hussies’ and ‘habitual little courtesans’ (pp.105-7) of the 1930s and the ‘good time girls’ of the Second World War and its aftermath. It is very clear from this analysis that the concerns about the 1960s ‘permissive society’ and 1980s worries about teenage pregnancies are part of a long line of moral panics about girls. The more contemporary concern about ladettes is, she argues, also a descendant of these trends, and not the hardest to identify. Here, the subtext of concern that young working-class women are gaining the freedom to behave like young working-class men has become the text.

This is both interesting and uncontentious, but what is more problematic is the question of how we should view concerns about raunch culture, the sexualisation of culture for young girls in particular, and the overlaps here with theories of rape culture. Dyhouse makes an explicit distinction between her position and that of writers who have highlighted raunch culture, like Ariel Levy and Natasha Walter. While Natasha Walter, for example, sees girls’ cultural options shrinking under tide of pornification, Dyhouse on the contrary argues that the successes of feminism have expanded women’s horizons. The temptation to view women as victims in need of protection should be resisted. Even so, Girl Trouble is not complacent about sexism nor the continuing need for feminist campaigning. Indeed, Dyhouse’s closing emphasis on the importance of women sharing their stories may well be thinking of efforts like the Everyday Sexism project. However, there is a difficulty here. There is the idea that young women are at risk of sexual violence if they use their hard-won freedom to be out in public without male protection or sanction. This can be seen as a reaction to that very freedom. It follows from this that we should be beware that efforts to highlight just how at risk women are, are themselves in danger of being co-opted to the reaction against women’s new freedoms, however feminist the intentions.

Both Everyday Sexism and Girl Trouble are more nuanced than this, but they can be regarded as representing two poles of opinion, one of which says that feminism’s priority should be in highlighting the sexism women still encounter, while the other concentrates on how women’s position has improved and sees the attempts to highlight remaining (or developing) sexist attitudes and behaviour as unhelpful. They are however united in their focus on male attitudes towards women, whether that is Times columnists in the 1920s or van drivers in the 2010s.

Attitudes and systems

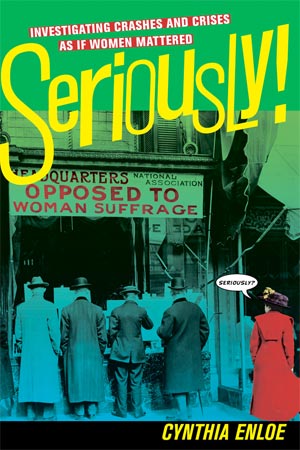

Cynthia Enloe, Seriously! Investigating Crashes and Crises as if Women Mattered (University of California Press 2013), xv, 242pp.

That the behaviour of some men demonstrates that, despite many decades of feminism, they still believe themselves entitled to women’s acquiescence and attention, and to react with abuse and violence if they don’t get it, is worthy of note, if depressing. There is a danger however in this focus, that in concentrating on individual attitudes, we might come to believe that the main task we face lies in changing those attitudes. The omission here is an understanding of the structural basis of sexism and how it works within capitalist society, and it is this which Cynthia Enloe addresses in Seriously! Investigating Crashes and Crises as if Women Mattered.

Investigating crashes and crises as if women mattered is a laudable ambition. Enloe’s focus in the early chapters in particular on women and work, whether as women in tribal societies, garment workers, public-sector workers or academics in women’s studies departments, reflects the material realities of women’s lives in a way which is absent from both Everyday Sexism and Girl Trouble. Ultimately however, much of Seriously! ends up as an analysis of what individual men think, rather than how the system of which sexism is a part operates.

This is particularly clear in the chapter on the economic crisis. Enloe argues that one of the causes of the 2008 crash was the ‘masculinised’, risk-taking culture of Wall Street:

‘if we ignore the U.S. financial industry’s deliberate cultivation of a particular kind of masculinity on the trading floor and its disparagement of femininity inside its most influential workplaces, we will see another financial crash in the near future’ (p.70).

It is undoubtedly the case that trading floors and financial institutions around the Western world have toxic work cultures and appalling degrees of sexism, racism and class prejudice. That the risky behaviour encouraged in individual traders can have serious consequences has also been amply demonstrated since Nick Leeson brought down Barings Bank. To blame this on ‘masculinisation’ however implies both that banks would have acted differently if they had more women in key positions and that the risky behaviour arises from something in the nature of men.

Enloe argues against this that some banking systems, like Canada’s, were similarly male-dominated but behaved more prudently. She also points out that an earlier generation of US bankers were regarded not as risk-takers but as ‘conservative, pin-striped, well-fed, and “solid”’ (p.66), so the modern model is ‘a kind of masculinity’, not the only possible kind. These do not seem particularly cogent defences and it remains difficult to see what to do with an argument about the malign effects of masculinity on banking which only seems to suggest that more femininity would help.

This appears to bring us to the version of feminism which counts the number of women on company boards, ignoring the fact that the interests of female members of the bourgeoisie are emphatically not the same as those of working-class women, and that this does not constitute equality. Enloe’s argument here disregards the system in which the bankers’ risk-taking was encouraged: the boom and bust cycle of late capitalism. The shift in the popular image of bankers, and bankers’ image of themselves, from conservative pillars of the establishment to buccaneers is illustrative of the development of finance capital, but the fact that these are also masculine images seems the least important aspect of this change.

As feminists, we need to be able to share our experiences of sexism today, and to understand how those experiences fit into the history of feminist struggle. These books reflect many positive steps in the movement towards empowering ourselves to discuss and challenge sexist behaviour. We also need however to understand how this behaviour fits within the structure of society and for that, unfortunately, we still need to look elsewhere.