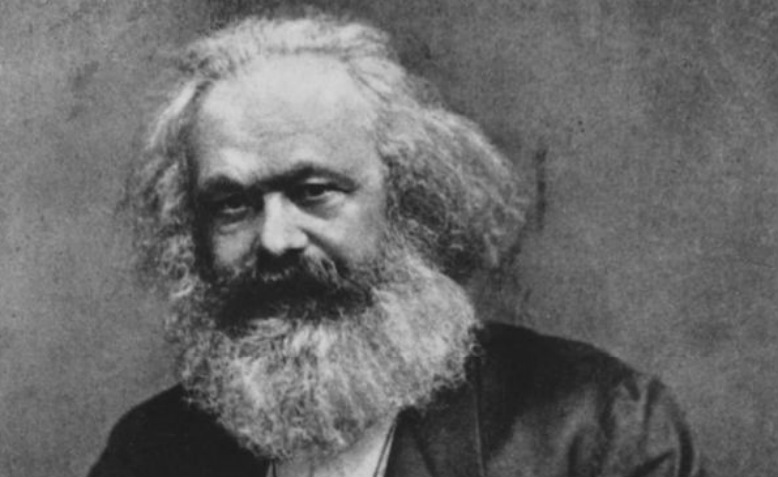

Karl Marx. Photo: Getty Images

Karl Marx. Photo: Getty Images

Despite the nonsense that gets talked about it, Marxism is a clear, powerful, and relevant philosophy, argues Morgan Daniels

Capitalism

The primary object of study for the German revolutionary Karl Marx was capitalism, a system which developed in northern Europe in the sixteenth century. A defining characteristic of capitalist society is that the means of production—factories, tools, land—are owned privately, such that human needs become commodities designed not to meet a common demand but to create profit.

One effect of this, Marx argued, is that questions of social class are greatly simplified. Society is now divided into two main groups: a ruling capitalist class (bourgeoisie) who own the means of production, and a vast working class comprising people who have no choice but to sell their labour power in order to make a living.

All capitalists are trying to maximise their surplus value. Running a factory is an expensive project, requiring a lot of investment. But once costs have been covered through sales, what’s left is surplus value—profit. In a gruesome chapter of Capital (1867) on the working day, Marx demonstrated how capitalists repeatedly find ingenious ways to get their surplus. Working hours are extended to the point of exhaustion, wages are reduced, children are employed at a nice cheap rate, lunchtime mysteriously disappears.

To work in the capitalist system is to experience what Marx called alienation. We expend considerable amounts of labour on a daily basis so that we can buy food and pay rent, but we are estranged from the products of that labour. A worker in a Toyota factory might make an exhaust pipe or a windscreen wiper, but she is at a remove from the completed commodity, the car, which is owned and sold by the boss. We are alienated, too, from society at large: each of us is connected to thousands upon thousands of others, because we are constantly interacting with the products of human labour—the clothes we wear, the furniture in our homes—yet it is precisely and only through such things that we ‘know’ one another. Marx even had it that we are alienated from our ‘species being’. Put otherwise, capitalism, for the very greatest majority, is a dehumanising experience.

A vital feature of capitalism is competition. Anarchy reigns in the capitalist economy—there is little planning, if any at all, with one manufacturer of shoes up against another, up against a third. ‘Free’ competition has a lot of serious consequences, not least overproduction: capitalism is a wasteful and inefficient system, one which gives us more shoes than we could possibly need whilst millions starve. (Thus, is implied, by the by, a Marxist analysis of climate change.)

Another point is that competition places a demand for constant growth on capitalists. A business owner cannot be content with the same modest amount of profit year in, year out, because if he does not innovate and seek out fresh markets, somebody else will. This relentless, insatiable capitalist quest for new vistas frequently finds expression in imperialism, as in the colonisation of India no less than the current attempts to open up Venezuela to American oil companies. In 1917 Lenin would describe imperialism as the highest stage of capitalism.

The capitalist system, then, is ruthless, premised on inequality. It both requires the exploitation of the masses and has a tendency towards war. And if that wasn’t bad enough, the bourgeoisie also own the means of mental production—newspapers (say) are big businesses. ‘The ideas of the ruling class’ wrote Marx and Friedrich Engels, ‘are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force.

Socialism

The picture is a distressing one, for sure, and since Marx’s time capitalism has only grown and grown into a truly global system.

Yet there can be no place for pessimism in a revolutionary analysis of the world. Marx was insistent upon a dialectical understanding of society, in which everything is ‘pregnant with its opposite’. Capitalist oppression, for instance, gives rise to resistance. Indeed, capitalism is distinguished by a very serious, nay fatal, contradiction: the working class, by definition, dwarfs the capitalist class in size. The bourgeoisie, therefore, ‘produces its own gravediggers’, as Marx and Engels argued in The Communist Manifesto (1848).

Attuned to the interplay of opposites, Marxists understand history as having to do with the antagonistic relationship between groups with differing interests—class struggle. The length and nature of the working day is a case in point, something which, for Marx, ‘presents itself as the result of a struggle, a struggle between collective capital, i.e., the class of capitalists, and collective labour, i.e., the working-class’. Workers’ rights have been fought for over centuries, always in the face of considerable hostility from the bourgeoisie, and the struggle continues today, with the rise of the ‘gig economy’.

The alternative to capitalism that generations of activists have tried to win is socialism. In a socialist society production would be determined by need, not profit, with the means of production owned collectively by workers. The argument for socialism is a liberatory one: it is not that we strive for a socialist world simply because it represents a more efficient way of organising production, though this is surely true, but rather that, shorn of the alienating demands of capitalism, working people would lead better lives.

Marx did not provide a blueprint for what a socialist society might look like. He was not a utopian. In the first instance, he wrote, socialism would necessarily be ‘stamped with the birthmarks of the old society’, which is to say informed by the capitalist system it had supplanted. The point, again, is a dialectical one: socialism emerges from capitalism, the latter demonstrating the tremendous productive capacity of the human race yet immiserating untold billions. Crucial, too, is that it is only under socialism that we might begin to figure out what it is we want from our lives—we will make collective, democratic decisions about anything from housing to farming, whilst also finding ourselves freed as individuals to explore the possibilities of human existence itself.

Revolution

How might we achieve socialism? One answer is that socialism can be delivered from above, which is to say that we merely need to elect socialist politicians who can then pass laws bringing about a fairer and more equal world. Any legislative change that improves the lives of working people is to be celebrated, of course. But such reforms are never granted magically from on high: they are the result of pressure from outside parliament, through mass movements.

We cannot sit and back and wait for socialism, but fight for it ourselves, and it is in this process of struggle that our ideas begin to develop. As Marx wrote in a vital section of The German Ideology (1845): the alteration of men [sic] on a mass scale is necessary, an alteration which can only take place in a practical movement, a revolution; this revolution is necessary, therefore, not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew.

Marx is clear: socialism must come with a revolutionary rupture. The state is not a neutral instrument which can be variously utilised for left or right-wing ends, but ‘a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie’, to quote The Communist Manifesto. Any and all attempts to impose socialism from above are limited by virtue of working within the strictures of a capitalist apparatus.

It is for this reason that Marx highlights the working class as the agent of revolutionary change. This is socialism not from above, but from below, a revolutionary socialism. The self-emancipation of the working class would necessitate us seizing control of the means of production and our political institutions, the vital first step towards a more democratic society.

Organisation

Marx was not some coffee house intellectual, observing political struggle from afar: he organised for change, for socialism, his entire life. It should be no different for us. Marxism is not a dispassionate means of surveying past, present, and future, but rather a mode of analysis implying the active drive towards radical change, with theory and practice informing one another. To organise together as socialists is the attempt to change the world for the better.