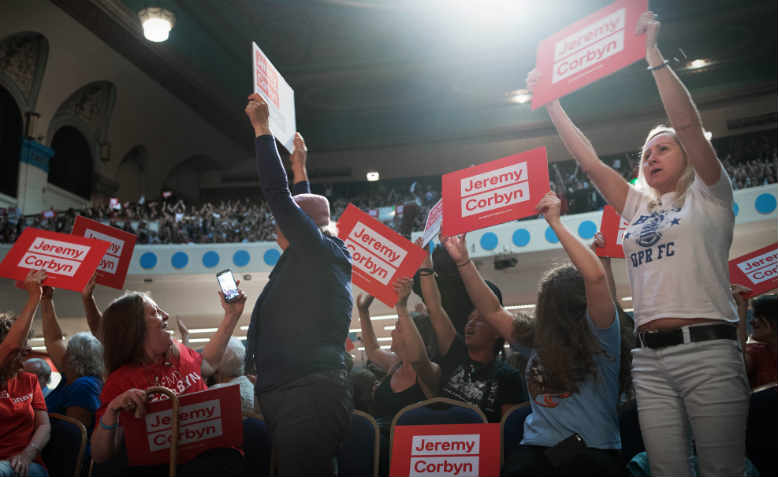

Corbyn supporters at a rally in London, August 2016. Photo: Flickr/Jim Aindow

Corbyn supporters at a rally in London, August 2016. Photo: Flickr/Jim Aindow

John Rees was interviewed for the Panama Magazine by Argentinian writer Mariano Schuster

When Tony Blair launched invasion of Iraq, he co-founded the Stop the War Coalition. When workers faced the Conservative Party’s attack on their living standards, he became a spokesman for The People’s Assembly against Austerity. His name is John Rees and he is now one of the most authoritative voices on the British left. To some people he is a radical influenced by his past activism in the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party. To other people, including this writer, he is one of the best exponents of the new popular movement against austerity policies.

John Rees’ work has many aspects. In addition to political organisation there are two books worth highlighting: his co-authored A People’s History of London and the forthcoming new book The Leveller Revolution. This anti-war activist rarely seems to rest. Here he gives an interview to Panama Magazine analysing the Corbyn phenomenon.

Rees was a colleague of the late Tony Benn and believes that this new process is an opportunity for a social mobilisation to the left. Although the right-wing of the Labour Party believes that Corbyn could never become Prime Minister, Rees has a different point of view. He says that what matters is the recovery of the centrality of social struggle. In this interview, he talks about the battle for the Labour leadership, and the wider prospects for the British left.

John, you have been an activist of the left for the most part of your life, did you ever imagine that someone like Jeremy Corbyn could be elected leader of the Labour Party?

It’s certainly not something that one could have imagined a while ago. In fact, not even Jeremy thought he could win the election when he was first put on the ballot. It was a complete surprise. It really only happened because the Labour Party’s rules have changed so that people could register as a supporter of the Labour Party for £3 (which is very little money) and then vote in the election. Thanks to that rule change, many people who had never been in the Labour Party – but that had maybe participated in the anti-austerity movement or the anti-war movement – joined Labour and, as they joined, they also altered the perspective of those within the party. And that is really what gave Jeremy the possibility of winning. So, unlike the last wave of Labour left activism around Tony Benn in the late 70s and 80s, which grew from within the Labour Party and within the trade union movement, this was something that came from outside, from the social movements intoLabour Party.

But also during the 1980s there were a lot of organisations supporting the Labour Party from inside and outside: The Militant Tendency, Trotskyist organisations, the strike of the mineworkers against Thatcher, where Benn also participated…

Yes, but it was very different. The membership of the Labour left has fallen steeply since those years. It was probably its lowest point ever just before Jeremy’s first leadership campaign. Previously the Labour left could rely on the mineworkers that demonstrated against the Tories and other union members for support. So it was an internal process. What is happening now is something that came from outside of the party. That’s how it the Labour Party has grown from 200,000 people to 600,000 members.

In this sense, a big part of Corbyn’s support comes from outside the Labour Party. If we were to make a sociological analysis, would you say that they were frustrated voters of the Labour movement?

Probably, most of them were Labour voters, even though some of them had already started to migrate to some other political options. Voters that maybe would have liked to vote for Labour Party, but didn’t vote for the Labour Party that was so devastated by Tony Blair. You have to remember that Tony Blair lost 4 million Labour votes principally because of the Iraq War. So there were a lot of disappointed Labour voters that began to vote the Green Party or other left parties, like Respect, where I was involved. But even the people who didn’t vote at all cannot be said to be an anti-political sector. On the contrary, it was a very active sector involved in the social movements.

When do you think that Labour lost its essence? With Blair or before Blair? With Neil Kinnock? With all that process that followed ‘the longest suicidal note in history’ as the Labour manifesto in 1983 has been called?

Yes, it was a defeat of Tony Benn followed by a defeat of the miners, which was a turning point. Although, I do not agree that Labour was ever an essentially Socialist Party. I prefer Lenin’s old definition: that it is a ‘bourgeois workers party’. It’s composed of workers, but its leadership (and definitely its right-wing, and this has been proved right now) are always more loyal to the political establishment than to the Labour Party. So, it’s been always very contradictory.

The possibility of a fracture of the Labour Party seems real now. If that happens, if finally it were impossible to keep united the left-wing and the right-wing of the party, could a new left organisation be born from this process? With activist forces like Momentum as support? Do you think that the Labour Party will be split? And would the social movement make a new party like Podemos with the Labour right in another party like the PSOE?

That is certainly possible but is too early to tell. To comprehend the Labour Party, two things need to be understood: one is that the Labour right are always more loyal to the establishment than to the Labour Party. They would rather lose elections than win under a left leadership. The other thing is that the Labour left is ultimately more concerned about party unity than fighting the right. If you listen to what is happening now, after Jeremy has won for a second time, it seems that we only won in order to start compromising once again with the Labour right, which is madness. But the reason for that is that what unites both wings of Labour Party is an entirely electoralist approach. Now, I’d rather see a genuine socialist party which supported every movement, supported every strike, which could see the importance of different fields of battle beyond the electoral battle. I don’t dismiss or undervalue electoral politics, but the question is where you put the weight. For the Labour Party, even the left-wing of Labour Party, elections come first and strikes and protests come second. For us, strikes, and protests come first and elections are necessary, vital, but a secondary step which should feed into other activity. A split will probably only come about if the right wing are so vicious and so stupid that they cause the split. I doubt very much that anybody on the left would lead a split.

Historically, the left never wanted to leave. Not even Tony Benn…

I think it’s a last resort. I worked with Tony Benn constantly, and no matter how bad it went in Labour, he was always loyal to the party. And although he worked with and respected those of us outside Labour, and he was very sympathetic, he never thought of joining in.

What do you think of the accusations of a Trotskyist infiltration? How would you answer those accusations?

When Trotsky articulated the idea of entryism it was supposed to be for a short period and in a very specific situation. He certainly didn’t have a view that it could ever transform a social democratic party into a socialist, let alone a revolutionary, party. So, the idea of Militant Tendency entryism, where you could be there decade after decade with the aim of controlling the party… that is not remotely based on what Trotsky said. And, to a certain point, it was a dishonest way of doing politics. I’ve never been impressed with that particular form of entryism. Now in Britain, no serious Trotskyist organisation is actually in the Labour Party. My organisation, Counterfire, isn’t in the Labour Party. The Socialist Workers Party, The Socialist Party, neither of them are in the Labour Party. As a matter of fact, there are probably fewer organised Trotskyists in the Labour Party than at any time. An absolutely tiny number. So what the Labour right is saying now is literally a red scare, with no factual basis. I mean, Momentum has 80,000 members. I would be surprised if very many of them are remotely Trotskyists.

What is Momentum? How can you characterise Momentum?

To begin with, I will say what it is not: it’s not a social movement. A social movement is, by definition, a multi-party organisation. Momentum is totally under Labour Party control. It’s very organised but it does not mainly mobilise for demonstrations or protests or meetings, but to back Jeremy for the leadership election and Labour in parliamentary and local government elections. So they can have 4,000 people working specifically in gathering voters, in phone banks and so on, for the leadership campaign. They probably would never do that for a strike, for a protest. I’m not saying this as a negative thing. It just means it’s an internal Labour Party group, not a social movement.

So, do you think Momentum can transcend Corbyn’s figure and endure over time like a leftist platform?

It may do. But it will be an internal Labour Party operation. In fact, it is very exclusionary. It doesn’t like to have speakers that aren’t Labour Party members, it doesn’s like being accused of working with the rest of the left. You can’t be an office holder in Momentum unless you are in the Labour Party.

When we see Corbyn from his videos and speeches, and we listen to his interviews, he seems to appear as a character of the social democracy but capable of negotiating with the radical left. Could the structure limit him?

Well, that’s true of Jeremy but it’s not true of Momentum. And it’s not true of the internal party operators around Jeremy either. Jeremy is practically a unique figure, even of Labour left. That is mostly because of his engagement with massive social movements. He was involved in Stop the War, and in the People’s Assembly. He is a very powerful and consistent grassroots campaigner. And of course he is structurally in a different position than he was before, and when you talk with Jeremy now he still has those politics, but he isn’t in the same place structurally.

Do you think that Jeremy Corbyn is a social democrat? One who believes that things can be changed within the system, or, on the contrary, as a reformist that wishes to transcend capitalism?

I think he thinks both of those things. I would argue that they are not compatible but there is a long tradition of left reformism, which believes that they are. Tony Benn had this view, and so does Jeremy. He works very closely with the revolutionary left, he understands the politics of mass organisation, but he also believes it can be mixed with a reformist method of transforming the system.

Tell me about Brexit. In the Labour Party they have accused Corbyn of not being a very strong campaigner for Remain. For some of us, as observers, it was odd he supported Remain when historically the left wing of the Party was traditionally Eurosceptic.

Jeremy, for his entire political career, had an anti-EU position. That was Tony Benn’s position and Jeremy subscribed to it. He came to support the idea of Remain under pressure from the Labour Party right. So he changed his position. However, even though he supported the Remain position he didn’t want to participate too much in the Remain campaign. He ran a more sceptical Remain campaign, and I think he should keep this position, because he’s got to be in contact with those areas of the country that were working class and voting Brexit. And I think it is also a good position now to argue for a progressive Brexit against the Tories.

As a left activist, do you think it is a new process for the left in the Labour Party or do you think that this will go beyond the party?

I think that, at this point, the struggle is focused on the Labour Party but it can transcend it. On the one hand, it has massively popularised socialist ideas. For a long period any socialist idea was difficult to express, but now millions of people are thinking like this. The social movements were very radical, very anti-capitalist, but they organised horizontally. Lately, many people define themselves politically and in party terms as members of the Labour Party. But we have to understand that these people didn’t grow inside Labour. Many people say: ‘If Corbyn goes, I go. I’m only there for Corbyn’. That shows a deep rejection towards establishment policies. That shows a generation of people who suddenly find a new channel in front of them, but if it doesn’t work they will not necessarily stay in Labour. So, that may change over time, and the Labour left should consider these movements. But it’s still too soon to see what is going to happen.

Corbyn’s opponents keep saying that he can’t win a general election. Do you think this is true?

I think that the most difficult thing is not to win a general election, but to make it to the general election. According to numerous surveys that take into account what people think, actually the British working class has never moved very far from the welfare state consensus. They love the National Health Service, they don’t love privatisation, they like the unions, they don’t like inequality, they are very close to Corbyn’s ideas in lots of ways. So I think he has got a good chance to win the general election, the question is, does he have a good chance to getting to a general election? There is a long time until 2020, the year of the election. Moreover, although he has put out a lot of good policy it cannot be heard over the noise that the Labour right is making. So in a way, if he doesn’t defeat the Labour right, he can’t articulate his policies that could convince millions of people to vote for him in a general election. So that’s where the battle really is.

Let’s imagine all of this already happened: Corbyn defeats the Labour right and finally gets to be Prime Minister. What happens with the programme?

Well, you always have to face that moment. For now, it’s the Labour right and the hostile media. After that moment, comes the next step: the reform programme. And that’s where all of the institutions of the state came into play: the civil service, the police, the army, the corporations, the Bank of England… And then, we are going to see what a parliamentary party can do. In that context, we would be entering a much more serious class battle. And that’s why many of us are insisting on continuing to support Corbyn, when, at the same time, we are putting an emphasis on strengthening class organisations, the strikes, the unions. Because that’s where you win battles.

The original transcript of this interview in Spanish can be found here.