It’s been reported that a female Dada poet and artist was in fact behind a famous modernist art work. Sue Tate explains what the fuss is about

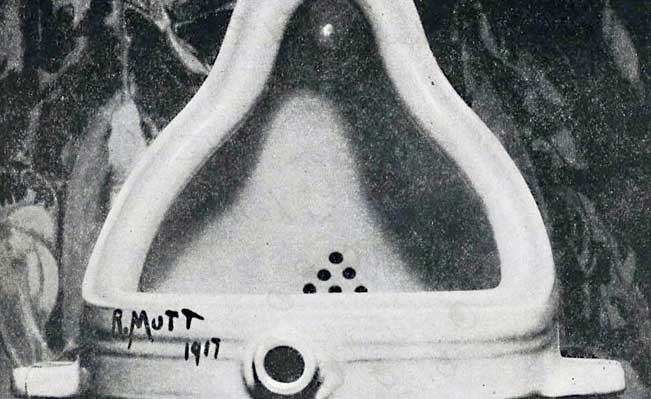

Yes, that urinal – “an icon of twentieth-century art” (tate.org), “the loo that shook the world” (Independent). Reputedly Marcel Duchamp (Dada* hero) signed a mass produced urinal R.MUTT and, in a radical gesture in 1917, submitted it to an open exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, New York, under the title Fountain. It was rejected in what is now seen as a crucial turning point in art. Since then it has been celebrated (and castigated!) as the starting point for all the subsequent installation and conceptual artwork that dominates contemporary art today.

But, as a convincing article in this November’s Art Newspaper argues, Duchamp stolethis iconic act from fabulous Dada poet and artist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

The evidence is pretty damning: two days before Fountain was rejected, Duchamp wrote to his sister (Dada artist Suzanne) to tell her that “one of my female friends, under the masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.”

It was not until decades later, in the late 50s/early 60s, that Duchamp, wanting to re-establish his position as an artist, started laying claim to Fountain. However he made a rather telling error: the supplier he says he got it from never stocked this particular urinal. The original was long lost but a photo survived (above) and Duchamp authorized his dealer to make copies that he authenticated and are now showcased in premier art museums around the world.

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, however, has been lost from mainstream histories. Friend and colleague of Duchamp, she made Dada sculptures out of found objects and had a track record in plumbing as art – the sculpture entitled God (below) was an S-bend mounted on a wooden block.

Jane Heap, the editor of an influential journal, The Little Review, described the Baroness as “the only one living anywhere who dresses dada, loves dada, lives dada” and published her poetry alongside the first appearance of James Joyce’s Ulyesses.

Born in Germany in 1874, Elsa acquired her title from her third marriage (to an impoverished aristocrat who deserted her) and pitched up (alone) in New York in the teens of the century, a fully formed avant-gardist. She was integral to the free verse movement and one of the New York Dada group that including Duchamp, Man Ray, Francis Picabia et al. She was outrageous, a kleptomaniac and proto punk challenging all codes of behavior, arrested for dressing in men’s clothes or not dressing at all (going about semi naked). One of the first performance artists she concocted and sported amazing costumes – tomato soup tins as a bra; hats of a bird cage (with bird) or a birthday cake complete with burning candles; tea-balls and cocktail spoons as jewelry. She shaved her head and lacquered it red, wore yellow face powder with black painted lips. She demanded equality in sexual agency and mused on ejaculation, orgasm, oral sex and impotence in her poetry which broke all boundaries of form as well as content.

Breaking the rules of gendered behaviour and totally uncompromising in her commitment to Dada, the Baroness was deeply threatening to the men in her circle. Just as I have argued in relation to Pauline Boty (Pop artist), I think that, as a woman, she perhaps presented a transgression too far: dying, poverty stricken, in Paris in 1927 she has been written out of the mainstream histories.

How different the story of 20th century culture would feel now if a woman had been acclaimed as an epoch shattering, free thinking, paradigm shifting creator.

But hang on. Scholars have been aware of the Duchamp’s letter since the 1980s! It’s in the news now because, although reprinting and praising the book in which the revelation is made, Museum of Modern Art (NY) has still refused to acknowledge Elsa’s role – as does Tate (check out Tate’s website account of Fountain no mention of Elsa!) And this deceit is the really shocking news. There is just too much is invested in the fiction of Duchamp’s heroic act. For a re-vision to be made acres of critical theory, art historical and curatorial analysis would, and should, be disrupted along with comfortable, (gendered) notions of genius and innovation,

And of course the Baronness is not the only women Dadaist to be marginalised. Check out this list of 10 women Dadaists you should know (do you?)

Doubly transgressive in rejecting both their social role as women and all accepted notions of art they offer a radical, innovative take on the Modernist shake up of art. Artists like Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven need to be put back into the frame – foremothers of punk, riot grrls, pussy riot et al and inspiration to all women challenging the status quo.

Notes

*Dada: early 20th century, anarchistic art movement – precursor of Pop and Punk.

Sue Tate is the author of ‘Pauline Boty: Pop Artist and Woman’

Maryland University hold a stunning collection of papers on Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (letters, poems, drawings etc) in their Special Collections.

Gammel, I. Baronness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity. The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2002.

Body Sweats: The Uncersored Writings of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven ed Irene Gammel

Baroness Elsa on Freytag-Loringham and New York Dada in “Women in Dada; essays in sex, gender and identity” ed Naomi Sawelson-Gorse 1998, MIT

Rene Steinke, Holy Skirts, (novel based on the Baroness’s life)