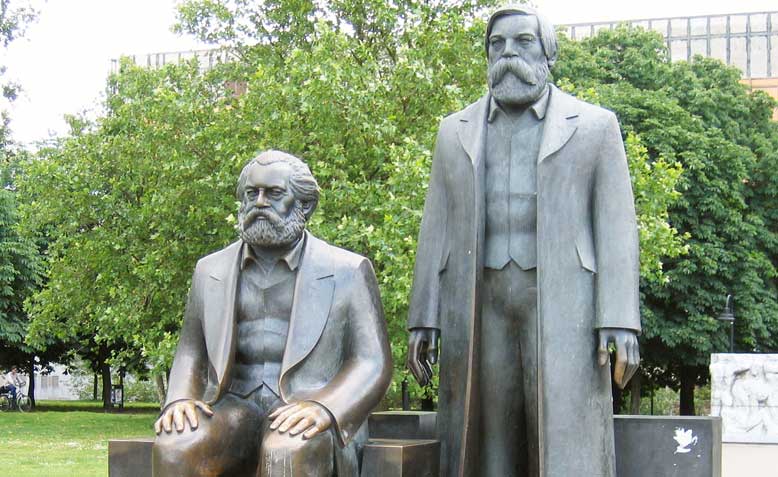

Statue of Marx and Engels in Berlin. Photo: Johann H. Addicks

Statue of Marx and Engels in Berlin. Photo: Johann H. Addicks

The world has changed dramatically since Marx’s day, but his ideas could not be more relevant, writes Dragan Plavsic

Karl Marx was born 200 years ago on 5 May 1818 in a provincial town in the Kingdom of Prussia, now in Germany. Who was he and why do his ideas remain relevant today?

Marx was the third of nine children born to middle class German and Dutch parents. At the time of his birth, a law barring Jews from the legal profession forced his lawyer father to convert to Lutheran Protestantism. The rest of the family followed suit in the 1820s when the six year old Marx was baptised. Brought up in a liberal household (his father was an enthusiast for Enlightenment ideas), Marx received a classical liberal education. But at university he began to outgrow his upbringing and turned instead to radically re-interpreting the ideas of the great German philosopher, Hegel.

Hegel had argued that the moving spirit of history found expression in the struggle between opposing ideas. But Marx thought Hegel had got things the wrong way round. Instead he argued that the motor force of history was the struggle between opposing social classes – between those who owned the wealth and those who laboured to create it – and opposing ideas were ultimately a reflection of this real life struggle.

This materialist way of thinking set Marx on the road to revolutionary conclusions.

As he was developing his ideas in the 1840s, capitalism was feverishly beginning to manufacture enormous wealth, the like of which had never before been seen. For the first time in human history, it became feasible to think – rather than merely to dream – of eradicating want and poverty once and for all.

And yet, simultaneously, a class of wage workers – a proletariat – was emerging whose atrocious life conditions were the very opposite of this wealth. Their struggles to improve these conditions made a deep impression on the young Marx. It was this proletariat – impoverished, exploited, dehumanised but unbowed – that Marx came to see as the one social force potentially willing and able to struggle for a new and genuinely human society. As he once famously put it, capitalism was giving birth to its own gravedigger.

Marx developed these ideas while becoming increasingly active in revolutionary politics. The Communist Manifesto, the pamphlet penned in 1847 with his great friend Frederick Engels, was commissioned by the Communist League, of which Marx and Engels were members. In it, they issued the famous clarion call, ‘Workers of all countries, unite!’

A year later, in 1848, as multiple revolutions erupted across Europe, Marx threw himself into the struggle. He became editor of a revolutionary newspaper and a leading advocate of radical democratic measures, including the freedom of oppressed nations from reactionary empires.

But these revolutions were only partly successful or they were defeated, and the proletariat where it rose up was bloodily repressed. Marx went into exile, eventually settling in London where he spent the rest of his life. There, in the British Library, he worked to give his ideas a theoretically rigorous or ‘scientific’ grounding.

One of the key questions he wanted to answer was what made capitalism tick, what its ‘laws of motion’ were. In particular, he wanted to explain where capitalist profits came from. Marx’s answer was as simple as it was eye-opening. In his great work, Capital, published in 1867, he showed that capitalists exploited workers by making sure workers worked for more hours than they were paid to. These unpaid hours of work were the source of all profits. Marx went on to demonstrate that competition for these profits was the root cause of economic crises.

At the same time in 1864 Marx helped to found the First International in order to unite a variety of left-wing groups committed to working class struggle. He was also a strong supporter of the Irish struggle for independence from the British Empire and of the Polish struggle for freedom from the Russian Empire.

But most importantly of all, Marx was one of the staunchest defenders of the Paris Commune of 1871, a working class uprising that in a few brief weeks before being brutally crushed gave the world a glimpse of what socialism might look like. For the first time workers seized power and elected their own delegates to run things on the basis of need not profit.

Of course the world has changed since Marx’s day. But his ideas remain relevant because our world remains plagued by many of the same problems. Classes still scar society. Profit still comes before need. Disastrous economic crises like the 2008 recession still happen. Empires like the US still use bloody violence to get their way. And nations like the Palestinians still have to struggle for freedom. But above all, we still have capitalism. Marx’s genius was to show that we cannot rid the world of its problems unless we also rid the world of capitalism.

To read more about the relevance of Marxís work for the 21st century, you can find a brief introduction in our book Marx for Today.