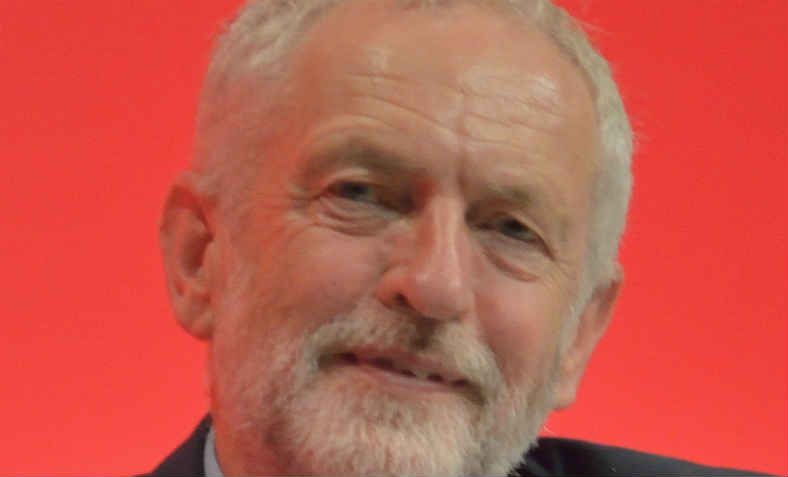

Calm and reasonable - Corbyn's debate victory. Photo: wikimedia, Rwendland

Calm and reasonable - Corbyn's debate victory. Photo: wikimedia, Rwendland

What are the lessons to be learned from Corbyn’s performance on Monday night?

Jeremy Corbyn didn’t just survive Monday night’s Battle for Number 10, he thrived on the audience’s questions and on Jeremy Paxman’s futile attempt to get him to admit that he wished Labour’s manifesto was more like the Communist Manifesto. Corbyn’s performance brought him accolades from a very wide range of people, including Nigel Farage and Douglas Carswell on the Brexit right as well as some liberal commentators, like Jonathan Freedland and Alistair Campbell, who have done so much to de-legitimise Corbyn’s leadership. Should we be surprised by both the performance and the reaction?

The first thing to emphasise is that when Corbyn is given the opportunity to speak, he is able to resonate with millions of people because Labour’s manifesto policies around redistribution, investment in public services, and social justice are actually popular with voters. According to YouGov research late last year, 45% of those polled support an anti-austerity platform as compared to 13% who favour continuing with the existing levels of cuts; 58% oppose any form of private sector involvement in the NHS while 51% are in favour of some degree of public ownership of the railways. Following the Manchester bombing, 46% of those polled agreed with the statement that the “UK’s military involvements abroad increase the risk of terror incidents in this country” as opposed to only 14% who believe that military intervention abroad decreases the risk of terrorism.

The problem is that the media all too often starts from a completely different place: that, as the BBC put it, “not taking a frontline part in foreign wars is also no protection against Islamist terror”, that nationalisation is a throwback to the 1970s and that Labour “has no hope of winning under Jeremy Corbyn”. If editors were truly in tune with the sentiments of their audiences, then they would have been far more open to interrogating the reasons for Corbyn’s success in two leadership elections instead of repeating a mantra about his lack of electability – a position that appears to be rebounding on them just a little.

This disjuncture between the views of ordinary voters and media’s preferred agenda frames was clearly demonstrated by Jeremy Paxman’s line of questioning. Yes he was aggressive with both Corbyn and Theresa May but he was aggressive to the prime minister on issues with which she is far more comfortable, including security and the Brexit negotiations where Paxman seemed endlessly to invite her to repeat the slogan that ‘no deal is better than a bad deal’. Corbyn, on the other hand was quizzed on those areas furthest from the Labour leader’s comfort zone and closest to tabloid headlines (and Conservative party HQ press releases): his alleged intimacy with terrorists and his attitude towards nuclear disarmament. What appears to have annoyed Tory commentators, however, is that Paxman’s “jeering irritability” simply rebounded on him: his interruptions (foisted on Corbyn far more than May) made the former “appear, at least in comparison, calm and reasonable.”

What are the lessons to be learned from Corbyn’s performance on Monday night?

First, despite some of the immediate positive reactions from across the political spectrum, sections of the press won’t let the facts of the debate distract them from their project to diminish Corbyn and Labour. The front pages of some broadsheets on Tuesday (‘Corbyn ducks terror challenge’, Telegraph; ‘May woos working class with tough line on Brexit’, Times) simply glossed over the fact that the audience “laughed with Jeremy Corbyn. They laughed at Theresa May”. Indeed, the entire tabloid press – including the Labour-supporting Daily Mirror – simply failed to register the debate in their headlines, presumably hoping that most people were watching the semi-finals of Britain’s Got Talent, (one wonders how the prime minister would have fared on that programme following her lacklustre performance).

Given the collapse in the Tory poll lead, we can now expect an intensification of attacks on Jeremy Corbyn and the Labour leadership that will further skew public understanding of the key issues. The most recent data from researchers at Loughborough University identified huge levels of negative press coverage for Labour across the press as a whole. The research was carried out before the respective manifesto launches and so the figures are likely to change to reflect the growing civil war inside Tory HQ following the debacle over their social care proposals. Nevertheless, we are hardly likely to see a more balanced or considered press agenda emerge in the week before the election. The stakes are simply too high for a Conservative press that has spent two years mocking Jeremy Corbyn.

Second, even the most sustained levels of media bias have their limits when faced with an angry and volatile electorate. After all, this is one that has largely withdrawn its trust in the press – the UK has the lowest levels of trust across the whole of Europe, a deficit of 51 points that makes it far worse even than Viktor Orban’s Hungary – and one that is desperate for a change to the status quo. Despite voices encouraging Corbyn to professionalise his media operation and to adopt a more conciliatory tone, it is precisely Corbyn’s direct engagement with voters and his refreshing passion for social justice that has seen Labour rise in the polls. His decision to tackle security issues after the Manchester bombing and, indeed, his refusal in Monday’s debate to endorse drone attacks no matter the context, is evidence that voters will respond positively to what is effectively a social democratic manifesto – if they are actually exposed to it.

That means that while we should never take our eye off media misrepresentation and distortion, the key for Labour supporters in the next week is to step up the campaigning for Corbyn in order to reach the maximum number of voters, to further open up the splits inside Tory HQ and to provide an alternative to the politics of despair and division.