This wasn’t an attack on humour or the Western concept of freedom but an outrage designed to produce a reaction of division and hatred – an outcome that we should do everything we can to resist

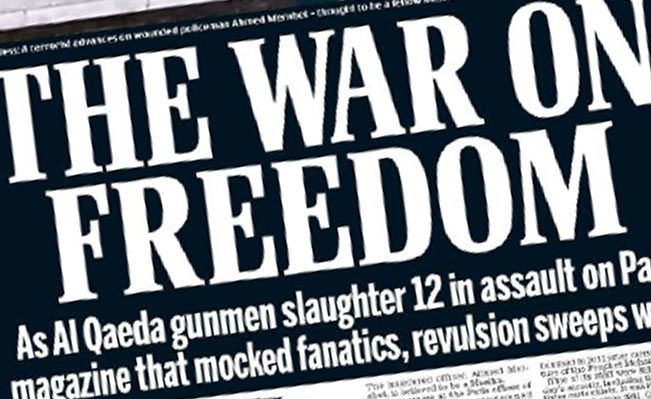

The horrific killing of ten journalists and two policemen in Paris on Wednesday has been widely described in the mainstream media as a ‘murderous attack on Western freedoms’, notably freedom of expression and the right to satirise. In response, some bloggers have insisted that the ‘attack had nothing to do with free speech’ but was simply part of the ongoing war between Western governments and jihadists.

The reality is that the killers did single out journalists and timed their attack to coincide with the weekly editorial meeting at Charlie Hebdo in order to secure maximum impact. The cartoonists now join the growing number of journalists killed ‘in the line of duty’. The Committee to Protect Journalists estimates that over 1,100 journalists have been killed in the last twenty years (with 60 killed in 2014 alone). They include not simply the high-profile murders of reporters by Isil in Syria but also cases like the 16 Palestinian journalists killed by the Israeli army in Gaza together with the 16 reporters killed by US military fire in Iraq. Strangely enough, these latter killings do not seem to have generated the same claims from leading commentators that they constituted a ‘murderous attack on Western freedoms’. Yet he fact remains that it is an outrage – whatever the identity of the assailant or the victim – that a single journalist should have lost their life simply for covering or commenting on a conflict.

But let’s be clear: what happened at Charlie Hebdo was not an assault on some generalised notion of press freedom but an attack on a specific news outlet that has regularly and proudly featured offensive images of Muslims (including publication of the hugely controversial Danish cartoons in 2006). The killings are likely to have been motivated not by a dislike of images per se but by the foreign policy dynamics of France and other Western states. The target, in other words, wasn’t an idea but, in the eyes of the gunmen, representatives of the forces with whom they are in conflict. So this wasn’t about some kind of ‘Islamic’ opposition to satire or free speech or evidence of some genetic flaw that results in the lack of a sense of humour but a violent act designed to spark a reaction – of increased anti-terror laws, of more surveillance, of more anti-Muslim racism – that will fuel the tiny ranks of jihad. It was, as Juan Cole argues, ‘a strategic strike, aiming at polarizing the French and European public.’

Those commentators peddling the argument that the shootings were all about a ‘mediaeval’ determination to stifle free speech and undermine our free media have sought to marginalise the wider political context as if there are no consequences for the ‘West’ of interventions in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan let alone the situation in Palestine. In their obsession with the sanctity of freedom of expression, they seek to bury the notion that there might be ‘blowback’ as a result of Western occupation and intervention along the lines predicted by the former head of MI5, Eliza Manningham-Buller, when she talked about how ‘our involvement in Iraq radicalised a few among a generation of young people who saw [it] as an attack on Islam’.

But of course it is far more convenient to adopt a ‘clash of civilisations’ thesis and to shunt aside uncomfortable geopolitical realities for the more soothing talk of free speech and absolutist speech rights. Yet even the liberal conception of free speech wasn’t designed to mean the freedom of the powerful to insult the powerless but precisely the opposite: to make sure that there could be a check on the most powerful groups in society and to protect the speech rights of minorities.

For some, however, free speech seems to be interpreted as the right to bully, to mock and to stereotype without regard for the consequences. Satire – all satire no matter the content or the target – is now treated as a basic hallmark of democracy. In this context, Will Self’s reaction to the Charlie Hebdo tragedy is instructive:

‘the test I apply to something to see whether it truly is satire derives from H. L. Mencken’s definition of good journalism: It should ‘afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.’ The trouble with a lot of so-called ‘satire’ directed against religiously motivated extremists is that it’s not clear who it’s afflicting, or who it’s comforting.’

In the last few days, moreover, the barometer of freedom of expression for many liberals increasingly seems to be about whether you’re ‘brave’ enough to publish material that you know is offensive to millions of people. Nick Cohen, for example, returned from Wednesday night’s vigil in Trafalgar Square not calling for unity and peace but hoping that ‘tomorrow’s papers and news programmes will prove their commitment to freedom by republishing the Charlie Hebdo cartoons.’ David Aaronovitch then used the freedom afforded by his column in the Times to warnthat those people who don’t share his view of ‘liberal’ tolerance that they should leave the country if they’re offended by the publication of the cartoons: ‘You live here, that’s what you agree to. You don’t like it, go somewhere else.’ But what kind of freedom is it that is measured by its ability to offend and not to enlighten and chacterised by an underlying threat that if you don’t like ‘my kind of freedom’ then you’re not free to live with me?

Many ‘muscular’ liberal commentators like Cohen and Aaronovitch have taken to the airwaves in response to the Paris outrage to argue that ‘political correctness’ and a widespread cowardice has taken grip with the result that too many media outlets are now self-censoring and are too nervous to circulate controversial material. But there is nothing ‘brave’ about large and powerful media institutions reproducing these images. The real reason why the vast majority of the British media has, thus far, chosen not to publish the cartoons is because there is a perception that publication would cause unnecessary harm and fan the flames of a situation that needs calming. That position may well change following what happened at Charlie Hebdo – it’s possible that some may hold back for fear of reprisals while some may publish and claim that this shows just how brave they are. A genuinely free media, on the other hand, would devote their resources to reporting on and monitoring power, to thinking about solutions to the problems we face, and to find ways to mark their independence that are not about sensationalism and cheap headlines.

In so much of the media coverage over the last few days, an horrific crime has been distorted to fit the prism of commentators fixated on a crude and absolutist fetish of free speech. Its real context – an asymmetrical and violent ‘war on terror’ – has been stripped from the scene. This wasn’t an attack on humour or on the Western concept of freedom but an outrage designed to produce precisely the reaction of division and hatred that we should be doing everything we can to resist.