Alex Snowdon: ‘We are the 99%’ is a magnificent slogan. It is unifying and helps us feel a sense of our power. But it has its limits when we move into analysis.

One of the most powerful and resonant elements of the Occupy movement is its defining, most famous piece of rhetoric. I refer to the juxtaposition of the 1% to the 99%, the power of which derives from its simplicity. It has justifiably been taken up around the world.

One of the most powerful and resonant elements of the Occupy movement is its defining, most famous piece of rhetoric. I refer to the juxtaposition of the 1% to the 99%, the power of which derives from its simplicity. It has justifiably been taken up around the world.

Speaking of the 1% versus the 99% focuses attention on the central issue of inequality, alerts us to the hollowness of capitalist democracy – we have politicians who serve a tiny elite not the vast majority – and reminds us that we, 99% of us, have a shared material interest, which is more important than anything that may divide us.

It is a magnificent slogan. It is unifying and helps us feel a sense of our power. But it has its limits when we move into analysis.

Here there are three potential problems. These matter because they all point to the danger of underestimating the obstacles we face. This can in turn have implications for the tactics we adopt.

It’s not so much the 1% part of the equation. It’s true that power lies with just such a tiny elite group. It is this group, too, that has continued to enrich itself even at a time of crisis and austerity, separating itself from even the upper echelons of the remaining 99%.

No, it’s the 99% part where simplification can limit us. Here’s why.

1) What about the middle class?

Our class structure is that a tiny percentage – 1% or less – forms a ruling class, while around 80% constitute the working class. In between these is the middle class, no more than 20% , which is largely made up of those who run small businesses and the managerial layers in both the private and public sectors.

Our class structure is that a tiny percentage – 1% or less – forms a ruling class, while around 80% constitute the working class. In between these is the middle class, no more than 20% , which is largely made up of those who run small businesses and the managerial layers in both the private and public sectors.

This middle class vacillates between the ruling class and the working class. Politically it tends towards the reactionary. The Conservative Party articulates the interests of the ruling class, but its membership and core support base are primarily in the middle class.

Elements of the middle class can rally behind movements led by the working class. Headteachers balloting for strike action on 30 November can be seen as an example of this in the public sector strand of the middle class. Something similar applies to doctors joining with trade unions and community groups in fighting the dismantling of the NHS.

But middle class people are also inclined to see themselves as apart from the working class, and identify themselves with preservation of the status quo. This makes them unreliable allies in struggle.

The existence of a middle class is one factor explaining why the 1% maintains its wealth and power despite being numerically tiny. To a certain extent it, however shakily, maintains the broad allegiance of a substantial chunk of society. The rhetoric of 99% taking on the 1% therefore brings with it the danger of obscuring the need for class-based politics, which recognises that the working class – directly exploited by the 1% and sharing a common interest – is uniquely placed to challenge the system.

2) What about ruling class institutions?

As with many other movements, there is uncertainty in the Occupy movement about where the police stand. Where the police have played an unambiguous role in enforcing the will of the ruling class – in Oakland, for example – experience has had a radicalising effect, turning protesters against the police. There’s nothing like being battered by a truncheon or sprayed by tear gas to make you realise the police aren’t on your side.

As with many other movements, there is uncertainty in the Occupy movement about where the police stand. Where the police have played an unambiguous role in enforcing the will of the ruling class – in Oakland, for example – experience has had a radicalising effect, turning protesters against the police. There’s nothing like being battered by a truncheon or sprayed by tear gas to make you realise the police aren’t on your side.

It has been common for the police to be regarded as part of the 99%. In the UK this has been given extra emphasis by the fact the police are facing cuts – so they come to be seen as potential allies, if we appeal to a shared opposition to cuts.

But the police are not on the side of the 99%. This is an institution that is designed to enforce the wishes and interests of the 1%. Police cuts are simply part of the Tories’ wider austerity agenda, but the government will continue to rely on the police to repress protest and undermine opposition. It is the social role of the police as an institution that matters – not the incomes of ordinary police officers.

This touches on a more general issue: we mustn’t underestimate the role of ruling class institutions in preserving the current state of things. We need to recognise, for example, the media’s role in maintaining the ideological hegemony of the elite. The ruling class maintains itself partly through institutions whose personnel reach down into the middle and working classes.

3) What about ideology?

The power of the 1% v 99% formulation lies in the way it crystallises our common interest. There may be all sorts of divisions and differences, but we have a great deal in common. We can unite and resist together.

But it is far from automatic for people to grasp who are their friends and who are their foes. Most of the ‘99%’ have contradictory ideas: one moment radical or progressive, the next moment conservative or outright reactionary. An instinct for working class solidarity can co-exist with racism, for example.

Indeed there are organisations which give expression to the most reactionary ideas and instincts. Far right groups, like the hardcore racist EDL (who recently attacked Occupy Newcastle) or fascist groups such as the BNP or National Front, cut directly against shared working class interests. They foster division over unity, scapegoating minority groups for problems which are in fact the responsibility of one particular minority group: the 1%, the ruling class.

It is therefore essential that anti-racism, and by extension opposition to all forms of discrimination and division, is integral to the politics of our movement. There can be no concessions to those who seek to divide the majority, turning us against each other instead of uniting to oppose a tiny, wealthy and powerful elite.

Why does this matter?

These three complications matter for a number of reasons, but what links them all is that they remind us the 1% has certain advantages which aren’t immediately obvious: a vacillating and relatively prosperous middle class, powerful ruling class institutions, and uneven and contradictory ideas among the great majority. These are all phenomena which need to be confronted if we are to make serious breakthroughs.

These three complications matter for a number of reasons, but what links them all is that they remind us the 1% has certain advantages which aren’t immediately obvious: a vacillating and relatively prosperous middle class, powerful ruling class institutions, and uneven and contradictory ideas among the great majority. These are all phenomena which need to be confronted if we are to make serious breakthroughs.

Firstly, working class movements – crucially the trade unions, but also broad movements like Coalition of Resistance that articulate working class interests and demands – are indispensable. These need to have concrete organisational form – they must be ongoing, not tied entirely to a specific tactical choice like street occupations. Secondly, the power of ruling class institutions, from the police to the BBC, must be contested.

Finally, we cannot evade the permanent ideological struggle – there is a battle of ideas inside the 99%, illustrating that political argument and debate runs through everything. The Occupy movement has already made a magnificent intervention in this ideological struggle, rallying opposition to the banks, big business and their political servants while pointing to an alternative set of priorities and values.

As the movement progresses, it will be necessary to sharpen understanding of some issues – and clarify demands – to successfully pose a challenge to an ideologically weakened but still powerful ruling elite.

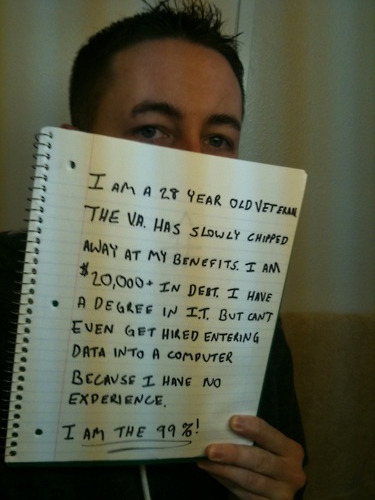

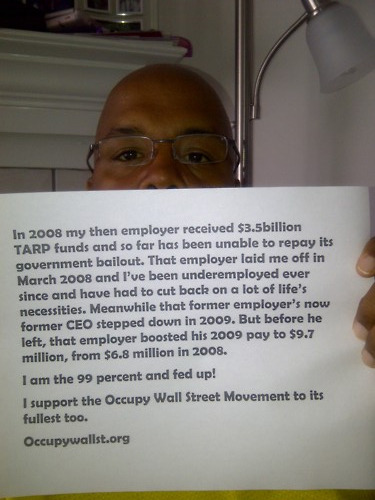

Images from We Are The 99 Percent website