This collection of writings on London has some striking moments, but is lacking class politics, despite its stated theme, finds Tom Lock Griffiths

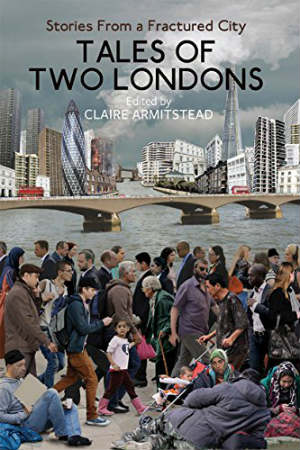

Tales of Two Londons: Stories From A Fractured City, ed. Claire Armitstead (O/R Books 2018), 274pp.

Tales of Two Londons,is to be lauded for its celebration of London as truly international and cosmopolitan city, with over two thirds of its inhabitants born overseas. It is also to its credit that it recognises the dichotomy of rich and poor in one of the most economically divergent places on earth, where billionaires brush shoulders with the homeless.

Ultimately, it fails however, and fails catastrophically, in that, in its recognition of difference, it bypasses (almost wilfully) any analysis of class. The single mention of the word ‘class’ at all in Claire Armitstead’s introduction is relegated to the past, to an anecdote about some midwives who delivered babies ‘of all classes and creeds’ (p.xvii). It’s a neat piece of alliteration, which is as shallow as the rest of her preface.

The introduction reeks with liberal heartache for a poor and ethnic other but refuses to engage in class politics or any serious critique of capital. Claire Armitstead’s aside about always disliking South London speaks volumes; her only reason to go there was when visiting one of its hospitals, giving rise to what she calls, ‘an intensely medicalised relationship’. The thought only dawns on her when reflecting back on the night her father died:

‘I watched the New Year’s Eve fireworks set fire to the sky on my father’s final night in a creepily empty private hospital wing above the railway station’ (p.xiv).

What exactly is ‘creepy’ about this is not of course that the hospital she was using was private, but its emptiness. One’s heart categorically fails to break for her.

Perhaps predictably a large part of her opening is devoted to Brexit.

‘2016’s vote to leave the European Union has profoundly shaken individuals and institutions across the capital. The majority of Londoners themselves voted to remain and were bewildered by the assumption of many leave voters outside the capital that they were an out-of-touch metropolitan elite. Now many long-term residents, either born or with family origins outside the UK, are questioning whether they have a future here at all’ (p.x).

The liberal calamity of Brexit is of course the urgent reason to undertake this attempt at a holistic, inclusive, re-telling of the story of London life. All other considerations and motivations are secondary.

Rightly so, however, there is a fair portion of the book that deals with the Grenfell fire. Here the book is at its strongest as the entirely avoidable disaster is the perfect symbol for much that is wrong with a divided London. The Grenfell fire exposes to us the poison at the heart not only of ‘Austerity Britain’ but also of all class society. As some comrades have pointed out, in a truly democratic socialist society the concerns of the residents would not, one would hope, have been ignored. And indeed, the residents did express serious concerns prior to the fire. It is good to see the Grenfell Action Group blog post included here from November 2016, several months before the fire. Its conclusion is chillingly prescient,

‘We will do everything in our power to ensure that those in authority know how long and how appallingly our landlords have ignored their responsibility to ensure the health and safety of their tenants and leaseholders. They can’t say they haven’t been warned!’ (p.12).

There are also some enjoyable contributions in this volume it must be said. Poetry from Omar Alfrouh and Ruth Padel stands out. Padel’s Walking The Fleet, takes us on a flâneur’s journey along a ‘sludgy dream-stream’ down the Thames. There are kitten-meat pies in Sophie Baggott’s, A History of London in Ten Street Foods, and tales of local campaigns to save lidos and pubs from gentrification and demolition. The inclusion of some text from The Akbaala Writing Group, based in London, is of interest too, offering us a collage of snapshots of refugee life in capital, of Eid celebrations and listening to Ed Sheeran on the radio. It’s all rather lightweight stuff though.

There’s an interesting passage from Memed Aksoy, the London based, British-Kurdish filmmaker. Aksoy was killed while covering the battle to retake Raqqa in Northern Syria from ISIS. His piece on growing up speaking Turkish and English, and Kurdish, a language banned in Turkey, is a poignant reminder of how languages are often a key battleground in the oppression of and resistance from marginalised peoples.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is the essay by Iain Sinclair, Flâneuse: Gummed Eyes, that stands out as the most thought provoking. This a discussion about photographic artist, Effie Paleologou’s ‘Microcosms’ series, a collection of close up photographs of discarded gum on the streets of London. As ever with Sinclair he can’t resist idiosyncratic phrases such as ‘arbitrary cartography’ and ‘the aesthetics of the insignificant’, though in this case these are the words of the artist used to describe her own work. Sinclair obviously delights in her approach and her psychogeographic practice, celebrating as it does the unseen and the mundane. He writes,

‘Gum is anti-food … To swallow would be to choke. Gum is a prophylactic … Gum is a wartime US import, a gift of cultural imperialism, thrown from the invader’s tank to the outstretched hands of children. Expanding pink balloons, puffed from lipsticked Lolita mouths, are unscripted speech bubbles from the Trumpist comic of the world’ (p.237).

Of course, it might well all be nonsense, but it is glorious nonsense all the same. In its surrealist, Debordian sludgy streams of consciousness we get closer to the lived experience of London than the anodyne autobiographical hand-wringing of Armitstead’s introduction. Sinclair also probably gives us the most cutting and memorable sentence on London:

‘London is multi-tonged, urgent. Cruel. London is everywhere, eyes wide open: exploited and exploiting’ (p.234).

There is, of course, lots of writing, art and filmmaking about London and its many contradictions. There are Sinclair’s many books including, London Orbital (2002) and Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire: A Confidential Report (2009), which along with Sebald’s body of work are the best examples of the flâneur’s approach to experiencing the city. In film too, there is Patrick Keiller’s wonderful, London (1994), and St Etienne’s collaboration with director Paul Kelly, A London Trilogy (2003-2007) and Julien Temple’s, London – The Modern Babylon (2012) which all offer new ways of looking at the capital.

For a radical history of the city that has class analysis right at its heart there is, A People’s History of London (2012) by Counterfire’s John Rees and Lindsey German. For an investigation into what the urban experience means in our political struggle to unseat capital, there’s the excellent Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution (2013) by David Harvey. Quite what this modest volume adds to this oeuvre isn’t really clear, but it’s a useful reminder of other work that surpasses it. I would strongly recommend that the introduction is missed out, but skip to some of the essays and poems, where some the voices of interest can make themselves heard through the comfortable fog of liberal anguish.

Tales of Two Londons: Stories From A Fractured City is available exclusively from the O/R Books website.