A special issue of the journal Race and Class vividly illustrates the history of black and anti-racist struggles for peace and equality in Britain, finds Dominic Alexander

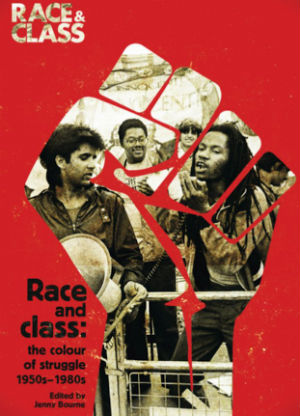

Race and Class: The Colour of Struggle 1950s-1980s, ed. Jenny Bourne, Race and Class,vol. 58, no. 1, July-September 2016.

The current number of the journal Race and Class is a special historic issue effectively giving a kind of history in sketches of anti-racist movements in Britain from the 1950s onwards. It comprises a series of articles and interviews, some new, some rescued from the archives, which together also span the decades of the Institute of Race Relations’ commitments to anti-racist and community struggles. For those who don’t know the IRR, its name might make it sound like a government approved institution, which indeed it once was, but in 1972 it was transformed into something quite different.

After black and radicalised white staff and members of the Institute were able to take charge, it became an activist organisation, committed to the campaigning, research and writing needed by the anti-racist struggle. The name of the house journal of the old government institute, Race, was changed to Race and Class, and the new strapline became, ‘A Journal for Black and Third World Liberation’.i The dozen pieces in this issue provide vivid testimony to a variety of the struggles, and a range of experiences and perspectives of Black working-class history. ‘Black’, for the tradition represented by the IRR, has a political meaning, denoting all those who are oppressed and exploited through structures of racism and Empire. The formulation consciously rejects official policies which would endlessly divide people into different particular ethnicities, which can usefully be put into competition with each other: given limited resources, should you fund a Punjabi women’s organisation or a Caribbean youth project?

Gathering these pieces and putting them on the historical record at this point in time has a serious political importance, beyond their undeniable individual interest. Jenny Bourne, in her editorial, argues that they are part of the demonstration that ‘black working-class communities were not just there to be “included” but were actually challenging and strengthening radical traditions and therein the nation’s history as a whole’ (p.3). The campaigns and struggles should be remembered because, while the history of ethnic minorities in Britain now has some official recognition ‘it tends to congeal around certain events and people in the public mind’ (p.3). Remembrance of black history now escapes ‘total exclusion’, but this new inclusion itself does not significantly challenge the structures of oppression and exploitation.

The selectivity is indeed marked; schoolchildren are now likely to be well aware of Mary Seacole’s admirable nursing work during the Crimean War (1853-56), but very few will have heard of the black London tailor, William Cuffay (1788-1870). Cuffay was a leading figure among the ‘physical-force’ Chartists of the 1840s; that is to say, he advocated revolutionary methods to acquire democratic rights for the working class in Britain. The limits of inclusion seem particularly revealed in the silence around this man who could so easily be held up as a hero of democracy.

The people and the campaigns in The Colour of Struggle are those from the post-war period of British history who also do not fit into any sanitised official narrative. Thus Claudia Jones, remembered cosily as a founder of the Notting Hill Carnival, but less so for her radical politics, is represented here by her denunciation of immigration controls in 1961 from the front page of the West Indian Gazette:

‘The gauntlet is down. The Tory-gloved hands which held it palmed a Colour-Bar Bill to restrict immigration of coloured citizens. They proclaim before the world that this is not to be a multi-racial commonwealth; but one in which the majority will be second-class citizens’ (p.119).

This collection of short pieces, then, amounts to more than a tribute and remembrance of these ‘unsung heroes of Black Britain’, but draws out the background of ‘a common experience of colonialism and racism’ (p.4), which brought together Africans, Asians and West Indians – as well as some white Dockers (pp.55-60) – together in solidarity against racism and imperialism. The complexities of experience are memorably, as always, expressed by A Sivanandan’s condensed version of his early life in the opening interview. A Sri Lankan Tamil with ‘roots in a village culture, living in an urban slum, going to the best Roman Catholic School and getting an English education’, he later arrived in London at the same time as the racist violence (or ‘race riots’) against black people in Notting Hill in 1958.

Interviews with Ansel Wong, of the West Indian Students’ Centre; Micky Fenn, an anti-racist Dockers’ union organiser; Martha Osamor, the tenacious community activist who came to Tottenham from Nigeria in 1965 (her daughter is the MP Kate Osamor); Vishnu Sharma, a Communist Party and Indian Workers’ Association activist from the Punjab; and Sadar Ali Malik, a Kashmiri union activist in Canning Town, all speak to the range of life-and-blood struggles to which so many people dedicated their lives. The title of Sadar Ali Malik’s interview is pithily expressive of the injustices the black working-class has had to fight: ‘Our blood in the British economy’ (p.111).

Racism is not a natural or inevitable phenomenon existing outside history, but has to be created and sustained in society and politics. Central to the structures of racism in post-colonial British society has been the violence against Black communities perpetrated by both the state and assorted racists and ‘neo-fascist’ groups. Colin Prescod’s 1978 report from the then new organisation, Black People Against State Harassment, and Michael Higg’s new essay, ‘From the street to the state’, both establish the connections between on the one hand, the far-right and racist violence, and on the other, the racism which emanates from the state and the establishment more broadly. One of the lessons to be drawn from these articles is that anti-fascism is necessary, but not enough; it is insufficient simply to protest against far-right organisations, if that protest is not part of a broader campaign that exposes the structural racism of the British state and society.

A crucial thread that runs through this volume is the lesson that the Caribbean, Asian and African people, who, from the 1950s onwards, were needed here by British imperialism as a labour force, were not passive victims of racism and exploitation. The article, ‘Striking back against racist violence in the East End of London, 1968-1970’ is based on new research, and is important evidence of how radical organisations in Tower Hamlets ‘looked to overcome the failure of the police and the political establishment to take appropriate action against racist violence by advocating for the politics of self-defence’ (p.50). This was, of course, denounced as ‘extremist’ and reduced to a matter of violence. Yet, it continued to be defended as legitimate and essential, not least by the IRR itself, as evidenced by an article from the Campaign Against Racism and Fascism in March 1979 by A Sivanandan and Jenny Bourne, ‘The Case for Self-Defence’.

So the Black working-class, through their own struggles to resist racism, to form their own institutions, communities, and solidarities, forced the state and ruling class, grudgingly to give way and make reforms. Sivanandan, in 1998, was clear that there should be no illusions about many of these concessions, embodied in such organisations as the Commission for Racial Equality:

‘These were not organisations set up to effect the integration of the mass of Black people in the country, but to create a tranche of Black middle-class administrators who would manage racism. They were set up as buffering institutions to deal with potential social dislocation’ (p.11).

It should be evident that all the issues raised by these testimonies and reflections on the history of anti-racism from the 1950s to the 1980s, remain as relevant as ever. The lessons learnt, and the examples of activism of the past, must all be remembered, if black people in Britain, and therefore all working people in Britain and the world, are to effect their own liberation. This issue of Race and Class is a fine contribution to that continuing project.

i Today the strapline is ‘A Journal on Racism, Empire and Globalisation’.